Dave Larock in Interest Rate Update, Mortgages and Finances

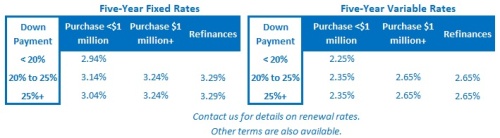

In today’s post I offer my forecast for five-year variable rates in 2018. (FYI - You can read my forecast for five-year fixed rates here.)

Also, at the end of the post I offer my take on whether five-year fixed or variable rates are likely to offer the lowest cost over the next five years and, more importantly, my take on which is the better option for most borrowers in the current environment.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) raised its policy rate for the first time in more than seven years over the course of 2017, from 0.50% to 1.00%, and lender prime rates, which variable-rate mortgages are priced on, quickly followed.

At the time, the BoC explained that it was clawing back the two 0.25% emergency rate cuts that it had made in response to the global oil-price shock because it was satisfied that our economy had completed its adjustment to lower oil prices, and additional rate hikes did not seem imminent. But then inflationary pressures continued to build and by the time 2017 drew to a close, the BoC was once again sounding hawkish about near-term rate increases.

Fast forward to today. The consensus expects the BoC to hike its policy rate again this Wednesday and to raise a total of three times over the next twelve months. This forecast is underpinned by steadily improving employment and wage data and also by recent sentiment surveys that show improving business confidence.

From a mortgage-rate perspective, the difference between five-year fixed and variable rates now stands at about 0.75% and if that entire gap disappears by the end of this year, variable-rate borrowers will wish they had locked in a fixed rate instead. But before we discard variable-rate options out of hand, we should remember that the consensus forecasts by our mainstream economists have predicted about ten of the last two BoC rate hikes since the start of the Great Recession (to borrow from an old joke), and that the BoC may not be able to tighten its monetary policy much more, even if it wants to.

If you added a magical truth serum to BoC Governor Poloz’s morning coffee, I think he would admit that all else being equal, he would like to continue to raise the Bank’s policy rate. Over the short term, it would help relieve rising inflationary pressures and slow household borrowing rates, and over the longer term, a higher policy rate would give the Bank more room to provide rate-cut stimulus when the next economic downturn hits.

But policy-rate changes don’t occur in a vacuum. They have a pervasive impact throughout our economy and can trigger negative side-effects that have the potential to strangle the hard-won economic momentum that the Bank’s monetary policy is intended to help preserve.

Here are some examples of the potentially negative side effects that the BoC must account for when it tightens monetary policy:

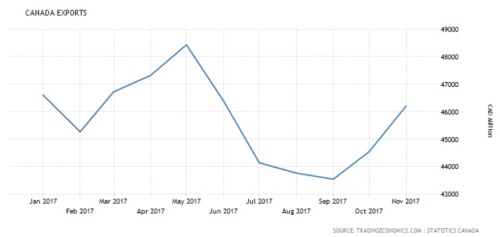

- A loftier Loonie – The Loonie recently rose to 80 cents versus the Greenback as the odds of a near-term BoC rate hike have increased. As the charts below demonstrate, it shouldn’t take long before export sales move in the other direction. The BoC has acknowledged that a strong export sector is vital to our economy’s long-term health and as such, the Bank must carefully weigh the impact that additional rate hikes will have on its momentum.

- Reduced consumer spending – Consumer spending is the largest driver of our overall GDP, and higher debt-service costs leave less money for other forms of spending. If consumer spending slows, the rising business confidence that has our economists so excited today could quickly dissipate (long before that confidence translates into increased business investment, which is what really matters).

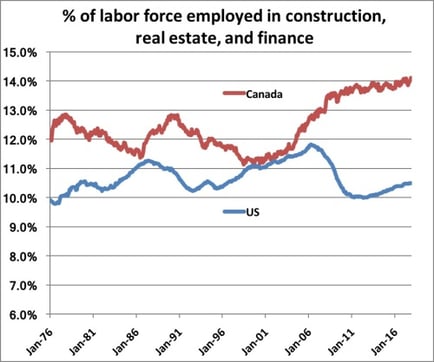

- Decreased demand for labour – Our labour market is in the midst of its best run since the start of the Great Recession. Higher interest costs will divert business capital investment that might otherwise increase the demand for labour. While it’s true that if the BoC wants to relieve inflationary pressures (which, in isolation, might be a desired outcome), the Bank should be careful what it wishes for because the most recent mortgage rule changes are also likely to have a significant impact on employment in 2018. Jobs in real-estate related sectors have risen sharply over the last decade and stand at record highs as a percentage of our overall employment (see chart below, courtesy of Ben Rabidoux of North Cove Advisors). If real-estate activity and borrowing slows, employment in these sectors is likely to decrease.

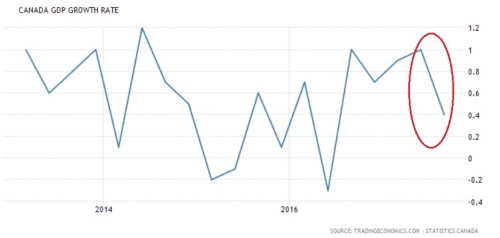

- A further reduction in GDP growth – Our overall GDP growth has been slowing since the summer and rate hikes that exacerbate the negative side effects listed above will slow it further. I think the Bank may choose to delay the next rate hike to preserve our already waning momentum (see chart below), especially given today’s elevated trade and geopolitical uncertainties.

The BoC has clearly stated its concern about rising inflationary pressures and about its need to anticipate the road ahead when setting its monetary policy. But here are some other elements, beyond inflation, that the Bank must also account for when looking down the road:

- Our inflation gauges are approaching their 2% targets but that’s after an extended period of below-target inflation. Now is a good time to remember that the BoC’s inflation “range” is between 1% and 3%. Given that, the Bank may not feel compelled to hike rates the minute that our inflation measures cross 2% (which is only the midpoint of the range).

- Average wages are rising nicely now but at +2.9% on a year-over-year basis, they still have room to grow before they reach a level that is likely to create significant inflation risk. According to a recent speech by Fed Chair Janet Yellen, year-over-year wage growth in the 4% to 5% range is more likely to fit that bill. And there is no guarantee that higher wages will even feed through into higher prices to a material degree – technological advances can improve productivity without the need for more labour, and many businesses face stiff price competition that will force them to shrink their margins instead.

- Long-term factors, as mentioned in my post last week, such as demographics, overall debt levels and technological advancements will exert downward pressure on inflation, reducing the likelihood that short-term price spikes will ultimately lead to runaway inflation. The bond market seems to agree because 10-year Government of Canada (GoC) bonds and U.S. treasuries, which are highly sensitive to changes in inflation, are still at ultra-low levels, and relatedly, the spread between 2-year and 10-year bonds is currently very narrow when compared to its long-term averages.

While the consensus expects the BoC to raise its policy rate next week and to tighten aggressively in 2018, I am not convinced that it will, for the reasons outlined above. That said, after seven years with no rate increases, I expect that variable-rate borrowers will have their courage tested much more regularly in the years ahead.

In terms of the age-old fixed-versus-variable debate, I think that variable rates will probably save borrowers some money versus their fixed-rate equivalents over the next five years. But I think that the amount saved is likely to be small relative to past periods because the gap between fixed and variable rates is still relatively narrow.

That leads to the next question, one which each borrower must answer: If my potential saving by going variable is likely to be small (assuming that you agree with my view above), is it worth the risk that I could end up with significantly higher costs because I didn’t lock in? And is it worth my worrying about that possibility?

In other words, is a potentially small upside saving worth the risk of a potentially much larger downside cost?

For my part, I see heightened potential for tail-risk events in the year ahead and I would be willing to pay somewhat more in interest to insure against them. (I think of the extra five-year fixed-rate interest you pay as a form of “rate insurance”.)

Specifically, I’m unsure about the impact of U.S. Federal Reserve and European Central Bank plans to withdraw a significant amount of liquidity from global financial markets this year.

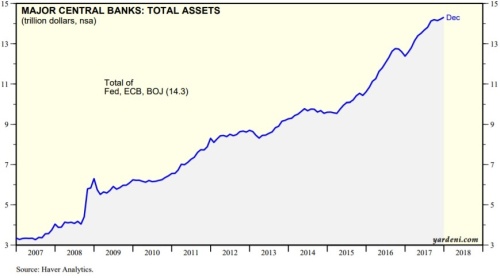

We know that the central bankers who oversee the world’s largest economies have been experimenting with unconventional monetary policies for the past decade and that their balance sheets have exploded (see chart below), but we can’t reliably predict what will happen when they start withdrawing that liquidity because these policies have taken us deep in to uncharted waters.

Against the current backdrop, my gut says that battening down the hatches makes sense.

If taking my advice ends up costing you more in interest over the next five years, you will have paid for rate insurance that you didn’t end up needing – but that still won’t mean that it wasn’t the right call. After all, when you buy fire insurance on your home, you don’t feel cheated when it doesn’t end up burning down.

Insurance has its place, and in today’s mortgage market, under our current economic circumstances, I think it’s worth paying for.

The Bottom Line: I don’t think variable mortgage rates will rise by as much in the coming year as the consensus now forecasts. That said, I favour the five-year fixed rate over the five-year variable rate for most borrowers in our current environment where economic risks are elevated. Not because I think it will save you money, but because we already know the extra cost of the five-year fixed rate today, whereas we don’t know the potential extra cost of a five-year variable rate tomorrow.

David Larock is an independent mortgage broker and industry insider specializing in helping clients purchase, refinance or renew their mortgages. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his own blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners Email Dave

January 15, 2018

Mortgage |