Fixed-rate mortgages offer stability, but variable-rate mortgages come with lower starting rates and, in most cases, produce net saving over the full term.

When the spread between fixed and variable rates is narrow (or non-existent) most borrowers lean toward fixed rates, but when it widens out, as it has of late, variable-rate options become more tempting.

It’s easy to understand why.

In addition to offering an upfront saving, variable rates come with the option to convert to a fixed rate at any time (at no cost) and a penalty of only three months’ interest if you decide to refinance or sell before the end of your term.

History is also on the variable-rate borrower’s side.

Five-year variable-rate mortgages have worked out to be cheaper than their fixed-rate equivalents about 85% of the time over the past twenty-five years. Granted, that performance was helped by steadily declining rates over that period, but variable rates don’t need that tailwind to continue winning.

In a flat or gradually rising rate environment, variable rates should still end up being cheaper about 70% of the time (according to detailed analysis done by Moshe Milevsky, a finance professor at York University).

However, all those advantages are offset, either in part or entirely, depending on the borrower, by inherent variable-rate risk. Today, the fears surrounding that risk are exacerbated by constant reminders that rates are near all-time lows, and, by inference, can only increase. But are those ominous warnings justified?

Here are three key points summarize my answer to that question:

1. How long before variable rates start rising?Our variable mortgage rates are priced on the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) policy rate, which currently stands at 0.25%.

The BoC has said that it doesn’t intend to cut further, so the only remaining question is when it will start to raise.

When COVID was in its early stages, the BoC’s best guess was that it wouldn’t start until the second half of 2023. Then our housing markets went parabolic, and the Bank became concerned that its pledge to keep rates at ultra-low levels for such an extended period was fueling that froth.

In April of this year, the BoC moved up the expected timing of its next rate hike to the second half of 2022, although it also took great pains to emphasize the uncertainty around its guidance (which I wrote about at the time).

The Bank supported its decision to advance its forward guidance by a more optimistic forecast, which was based largely on the belief that our economy will soon be buoyed by an export-led recovery. For anyone keeping score at home, that’s the very same export-led recovery the Bank has been using to justify its overly optimistic forecasts since former BoC Governor Mark Carney was leading it through the Great Recession of 2008.

As I keep writing, it’s hard to imagine that export-led recovery materializing next year if the BoC hikes well ahead of the US Fed. The last time it did that was in 2010, and that decision caused the Loonie to soar against the Greenback. Our export sector didn’t recover to its pre-Great Recession levels until late 2015, which was when the Fed and BoC’s policy rates came back into alignment.

Simply put, I don’t think the BoC will raise much ahead of the Fed, and I expect that will not occur until the second half of next year.

This admittedly contrarian view grows less controversial by the day as more cracks in the mainstream narrative appear. To wit:

- The consensus believed that inflationary pressures would force the Fed to advance its rate-hike timetable, but the Fed (and the BoC) insisted that the current inflation run-up would prove transitory. The bond market now appears to buy that view because yields have come well down from the highs reached when that debate was at fever pitch.

- It is increasingly clear that the pandemic won’t have a definitive end date with everything returning to pre-pandemic normal shortly thereafter. The rise of vaccine-resistant COVID variants means that precautions and elevated uncertainty will remain with us for the foreseeable future.

- Generous government stimulus programs and payouts on both sides of the 49th parallel haven’t spring-boarded our economies into sustainable and robust growth as the consensus expected. Instead, it is increasingly apparent that these programs provided only a short-term sugar high that will fade shortly after they are withdrawn.

- The spike in our household saving rates isn’t working out to be the temporary phenomenon that many predicted. Instead of the high-spending Roaring Twenties, it now appears increasingly likely that we’re headed for the Boring Twenties. The pandemic, like so many other significant economic events, has led to some permanent behaviour changes. For example, many households now view the excess cash on their household balance sheets as disaster insurance, not fun money waiting to be spent.

- Not surprisingly, businesses, after what they have been through, are also more cautious. Many are choosing to adapt to supply shortages rather than invest in expensive alternatives that would allow them to replenish their inventories more reliably.

I think we’re still in the middle innings of the pandemic, and that’s particularly important when we remember that the BoC and the Fed have both said that they won’t raise their policy rates until their respective economic recoveries are complete (rather than in anticipation of that outcome).

That’s a high bar, and one I think we’re still a fair way from clearing – especially if we’re back to the BoC’s old standby of waiting for an export-led recovery to kick into gear.

One other point on rate-hike timing.

While fears about possible run-away rate hikes will never go away, the mere fact that rates have been at ultra-low levels for years doesn’t necessarily tell us much about when they will rise in future.

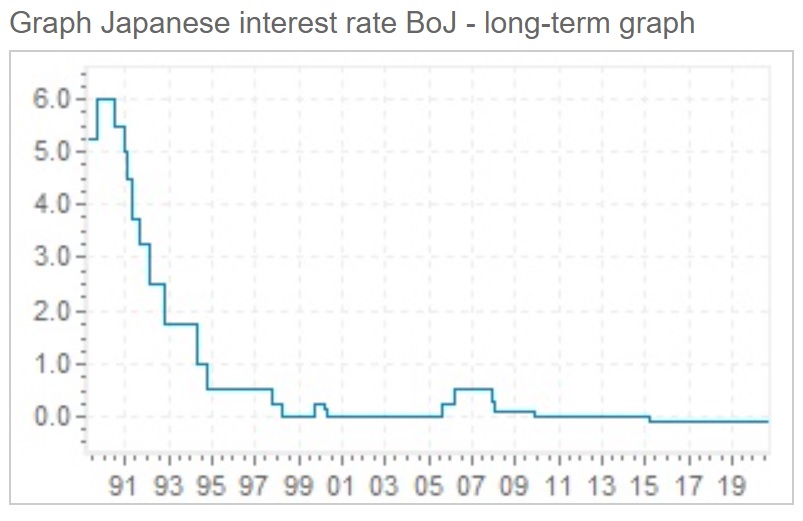

For example, Japan was the first country to adopt monetary policies like those used by the BoC and the Fed today.

In the early 1990s, in response to its own financial crisis, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) collapsed its policy rate and undertook massive quantitative easing (QE) programs. Many a prominent forecaster predicted that hyperinflation and spiking interest rates would follow. Those who bet on that outcome got carried out one after another, as shorting the Japanese bond market became known as a “widow-maker trade”.

The chart below shows the path of the BoJ’s policy-rate.

2. When variable rates do start to rise, how high will they go?

The BoC has logically predicted that today’s record high debt levels will magnify the impact of each rate hike, and it expects that it won’t have to raise by as much as in past tightening cycles to bring inflation to heel.

(For historical reference, the average BoC tightening cycle has typically comprised six 0.25% hikes, for a total rise of 1.50%.)

If the Bank expects the impact of each rate hike to be magnified, it is also likely to raise more gradually to allow time for our economy to absorb each increase. By the Bank’s own estimates, each hike can take anywhere from 12 to 24 months to reach its full impact.

Rate hikes wouldn’t likely be spaced that far apart, but if they are stretched over a longer than normal timeline, that too will extend the period of saving for variable-rate borrowers.

3. When will the BoC next cut rates?

The Bank’s next rate hike is unlikely to be the starting point for an inexorable rise thereafter, as some market watchers warn. That’s because the start of the BoC’s next tightening cycle will also create room for subsequent rate cuts.

If you’re starting a five-year term today, you will likely experience both over that period.

Choosing a variable rate requires the same discipline as long-term investing. If you start with a variable rate and convert the first time that it looks as though your rate might rise, you are very likely to end up paying more interest than you would have if you had chosen a fixed rate (because between the time you started your variable-rate term and when you want to convert, fixed rates will likely have risen in the interim).

Variable rates don’t win out because they are always lower than fixed rates over entire five-year periods. They win out because their average cost is lower over most five-year periods.

It’s okay (and normal) to be concerned about variable-rate rises, but when they occur, it is also worth remembering that they also often hasten the arrival of the decreases that follow.

A few final points:

If you want a variable rate today, you have to qualify based on the current stress-test rate of 5.25%, even though your starting rate will be in the 1.25% to 1.35% range.

In other words, lenders will only approve your loan if your family income can support a rate that is 4% higher than the one you are a paying. That hurdle ensures that anyone opting for a variable rate isn’t likely to end up on the street because they didn’t opt for a fixed rate.

If you do opt for a five-year variable rate, I strongly recommend using your discretionary prepayment allowance to increase your regularly scheduled payment to what it would have been if you had opted for a five-year fixed rate.

Ploughing your variable-rate saving back into your mortgage will increase the speed with which you are repaying it, and if/when your variable rate rises, you can toggle back some or all those discretionary payments to absorb the rise in your regular payment. Doing that will keep your monthly cash flow unchanged for the first few BoC rate hikes – if they happen.

The Bottom Line: The five-year Government of Canada bond yield continued its slow decline last week, and lenders are starting to drop their five-year fixed rates in response.

Variable rates held steady, and variable-rate discounts are now about as large as I can remember.

I continue to believe that there will be downward pressure on fixed rates as investors lower their expectations about the timing and pace of the recovery. Despite that, for all the reasons outlined above, I continue to believe that variable rates are still a better option for most borrowers.

August 23, 2021

Mortgage |

%20(2).jpg?width=687&name=Rate%20Table%20(August%202%2c%202021)%20(2).jpg)