Here are five key observations relating to last week’s jumbo-sized Bank of Canada rate hike.

The Bank of Canada (BoC) surprised markets last week with a super-sized 1.00% rate hike. Its policy rate now stands at 2.50%, a substantial increase from its 0.25% level in March.

Variable mortgage rates will rise by the same amount in short order, and that will increase each variable-rate borrower’s payment by approximately $53/month for every $100,000 in principal outstanding (assuming a 25-yr amortization).

The BoC justified its larger-than-expected move by predicting that a front-loaded jumbo increase now would decrease the total amount of tightening needed to bring inflation to heel and thereby increase the odds of a soft-landing for our economy.

The Bank continued to assess that most of our current inflation pressures are being caused by factors beyond our borders. But it also provided data showing that those external price pressures, particularly in food and energy, have caused other price increases across a broad range of domestic goods and services.

As our inflation spreads, it becomes stickier, as do expectations that it will remain elevated for an extended period. This increases near-term demand, as consumers and businesses accelerate their purchase plans to avoid further price increases and workers use their increased bargaining power (currently being boosted by labour shortages) to secure pay increases that help recover their lost purchasing power.

Those developments, now evident, are causing prices to rise higher still and increase the risk that a self-reinforcing cycle may take root, where expectations of price rises beget more actual price rises.

The BoC is clearly determined to wrest back control over inflation before it permeates much farther into our economy. It acknowledged that its sharpest rate hike in more than 30 years, and the additional hikes that it warns are likely to follow, will cause pain for many Canadians. But the Bank now finds itself backed into a corner with no good options left, so that damage control is now its unspoken, but overriding, theme.

Here are five key observations relating to last week’s BoC rate hike:

1. They’re not done yet.

In his accompanying press conference, BoC Governor Macklem indicated that the Bank plans to raise its policy rate a little above its neutral-rate range over the near term. (As a reminder, the neutral-rate range describes the rate level that neither stimulates nor reduces target inflation when the economy is operating at full capacity.)

In its recent publications, the BoC has estimated the neutral-rate range to be 2.25% to 3.25%, but last week Governor Macklem revised it down to be between 2% to 3%. Barring any further surprises, it sounds as though the Bank plans to keep increasing its policy rate until it reaches a little above that range, to about 3.25%, before pausing and allowing time to observe the cumulative impact that its succession of hikes is having on our economy.

(A policy rate of 3.25% would push offered five-year variable mortgage rates up to almost 5%, only slightly below most of today’s five-year fixed rates.)

2. Their credibility took a hit (and may take another before long).

While most of the recent hit to the Bank’s credibility has centred on its promise to keep rates at rock bottom for much longer than it was ultimately able to achieve, most informed observers would grant that this promise was understandable given the conditions at that time. It is also understandable that unexpected external factors like the war in Ukraine and new Chinese lockdowns made the current inflation spike difficult to predict.

But the BoC has less room for forgiveness now that the war and resurgent pandemic forces are there for all to see. On that note, after taking those important economic drags into account and layering on substantial monetary-policy tightening, I think the Bank’s soft-landing forecast will prove to be pure fantasy.

In its latest Monetary Policy Report, the Bank forecasts that US GDP growth will bottom out at 1.1% in 2023 and 2024, but it then forecasts that our economy will grow by 1.8% and 2.4% over the same time period. The Bank justifies this optimistic projection for domestic growth by predicting that high commodity prices and their heavy influence on our export sector will provide our economy with a tailwind that will help counteract the negative effects of rising rates.

But the prices of several of our main commodity exports such as oil, wheat and lumber have already turned well down from their recent highs. Further, if GDP growth slows to a crawl in the US as the BoC forecasts, falling demand in our largest export market could easily cause those prices to fall farther.

If we’re betting on whether either Canada or the US will feel the pinch of rate hikes more, it seems far more useful to compare our household-debt-to-GDP ratios. The current gap is wide, unusually wide, and shows that the US is far better positioned (see chart).

%20July%2c%202022.jpg?width=891&name=Household%20debt%20to%20GDP%20(CDN%20vs%20US)%20July%2c%202022.jpg)

Also, since rate hikes will have their biggest impact on the most interest-rate sensitive parts of our economy, it stands to reason that activity in both of our real-estate sectors is going to take a hit.

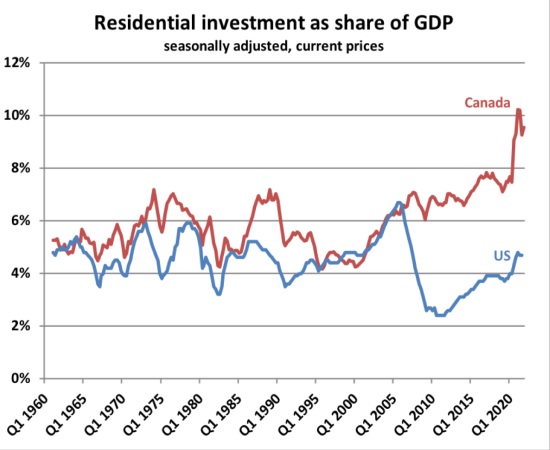

Here is a recent chart from analyst Ben Rabidoux showing residential investment as a share of overall GDP in Canada and the US:

Simply put, because the US has much lower relative debt levels and is much less reliant on real estate for its overall economic growth, those factors portend a softer landing south of the border. By these widely accepted standards, the Bank’s GDP forecasts for Canada’s economy look way too optimistic.

3. The BoC expects pain in our real-estate markets.

When the pandemic hit and the BoC was worried about a repeat of the Great Depression, it welcomed demand from all sources, including the real-estate sector, and Governor Macklem was happy to encourage Canadians to buy real estate under the assumption that “interest rates will be low for a long time”. Rock bottom rates, combined with that reassurance, set our housing markets on fire, and, as the chart above shows, our real-estate sector delivered the demand the Bank was looking for in spades.

Fast forward to March 2022 when the BoC first started hiking its policy rate and BoC Deputy Governor Toni Gravelle noted that there was “a high degree of vulnerability” in some of our housing markets, including Toronto and Ottawa, and he seemed to reassure Canadians at that time when he said that the Bank would be watching our housing markets “very closely and carefully”.

Observers took that to mean that if rate hikes led to seriously adverse impacts on real-estate prices and affordability, the Bank would adjust accordingly. But as with so many things that the BoC has said of late, that was then, and this is now.

In the opening statement of his press conference last week, Macklem noted that housing is cooling from “unsustainably high levels” (which I remind you were caused as a direct result of BoC policy) and he conceded that highly leveraged Canadians are going to experience some pain.

That should put paid to the belief held by many Canadians that the BoC has the housing market’s back.

4. There are signs that our economic momentum is already slowing.

As part of its messaging, the BoC wanted to reassure Canadians that our economy can handle the negative impacts from sharply higher rates, and to that end, it noted our “strong demand”, “robust consumption”, “solid” business investment, and export sales. While the Bank acknowledged that its tightening would cause growth to slow, it currently forecasts a drop from 4% (a figure that seems very optimistic to me) in Q2 to 2% in Q3.

It normally takes quite some time before rate hikes exert their bite, but it may not take as long this time. Our GDP contracted by 0.2% in May on a month-to-month basis, confirming that our momentum was slowing even before Q3 started. Our economy just shed an estimated 43,000 jobs in June, and activity and prices in our important real-estate sector have already slowed sharply. Those developments may be early signs that our high levels of indebtedness are significantly magnifying the impact of rate hikes, as many, including this blogger, have long predicted.

5. Rate cuts may not be as far off as they appear.

I continue to believe that our economy will prove more sensitive to rate hikes than the BoC expects, and if I’m right, the higher the BoC’s policy rate goes, the more it will hasten the arrival of rate cuts on the other side of the cycle (as distant as that prospect may now seem).

The US futures market, despite forecasting rates in an economy with much less household debt and much less reliance on real estate for its economic momentum, shares a similar view. It currently forecasts that the US Federal Reserve will double its policy rate from its current level of 1.75% to 3.50% by the end of this year but is also forecasting Fed cuts of 0.75% in 2023.

If the Fed cuts next year, at the very least, I would expect the BoC to be following close behind.

So, what to make of all of this if you’re in the market for a mortgage or if you currently have a variable rate and are thinking of converting to fixed?

If you’re a prospective home buyer, the silver lining in all the rate increases is that they are already helping to lower house prices. It may take some time to establish a new equilibrium, because rate hikes happen quickly and prices can be sticky on the way down, but there should be some price offset to help cushion the blow of higher borrowing costs.

If you’re choosing between fixed and variable rates today, the discount offered for taking on variable-rate risk is now back to about 1% but will likely continue to narrow over the remainder of the year.

The appeal of fixed rates in such a volatile environment is certainly understandable, especially now that locking in comes with a relatively smaller increase in your rate. The most important advice I would offer to anyone considering fixed-rate options is to ensure that their mortgage contract doesn’t come with onerous penalties that would eliminate the potential to save by breaking early to refinance (if today’s sharply higher rates do end up retreating before the end of your term).

I continue to believe that five-year variable mortgage rates are likely to save money over their fixed-rate equivalents over their full five-year terms, for reasons outlined above, even if the ride will be bumpy for a while.

I think it is also worth repeating the astute statistical observation made by fellow mortgage broker and Globe and Mail writer Rob McLister, that “when the prime rate is more than 50-per-cent above its five-year moving average, variable rates historically cost less in the next five years than five-year fixed rates, well over nine times out of 10 [going back to 1945].” He added, “The reason is simple: monetary policy works. Higher rates beget lower rates. That’s the beauty of rate cycles, and it’s why variables will ultimately be the only term of choice.”

Last week’s jumbo rate hike by the BoC took an axe to the huge spread between fixed and variable rates, and at this point there is nowhere left for mortgage borrowers to hide from sharply higher rates.

As Robert Frost once wrote, “The only way out is through”.

.jpg?width=883&name=Rate%20Table%20(July%2018%2c%202022).jpg)

The Bottom Line: Five-year Government of Canada bond yields finished lower again last week. That means that there is plenty of air under today’s five-year fixed rates, putting downward pressure on them over the near term.

Variable-rate discounts held steady last week but will be moving higher now as lenders increase their prime rates to match the BoC’s 1% hike last week. And, as per point #1 above, these rates are likely headed higher by about another 0.75% before the end of the year.

Image Credit: iStock/Getty

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

July 18, 2022

Mortgage |