The Bank of Canada (BoC) held its policy rate steady last week. That means our variable mortgage and home-equity line-of-credit rates will remain at their current levels, at least for now.

In its policy statement, the Bank observed that our economy slowed in Q2, led lower by consumption and housing activity, which are two of the most interest-rate sensitive parts of our economy.

This is the clearest evidence yet that the BoC’s ten rate hikes thus far are increasing their bite, but slowing momentum hasn’t done much to cool inflation pressures thus far.

The BoC noted that measures of core inflation remain elevated, that overall inflation pressures are still “broad-based”, and that it has seen “little recent downward momentum in underlying inflation”.

Furthermore, the Bank expects our Consumer Price Index (CPI) “to be higher in the near-term”, repeating its warning that “the longer inflation persists, the greater the risk that elevated inflation becomes entrenched”. It also reiterated that it “remains concerned about the persistence of underlying inflationary pressures and is prepared to increase the policy interest rate further if needed.”

If the BoC had released its policy statement the day before its actual rate decision, I think everyone would have expected another hike.

Instead, after the Bank held, the consensus take is that its hawkish language was a precaution designed to ensure that Canadians wouldn’t over-react to its decision to hold steady, as we did when the Bank announced its last pause back in January.

I don’t share that view.

The BoC may be done with rate hikes for now, but last week’s decision could easily prove to be a skip instead of a pause.

Slowing economic momentum is a necessary but not sufficient condition for returning inflation to its 2% target. Some costs are stickier and less sensitive to the BoC monetary policies, and there is urgency for the Bank to restore price stability before expectations of higher inflation become entrenched (and self-reinforcing).

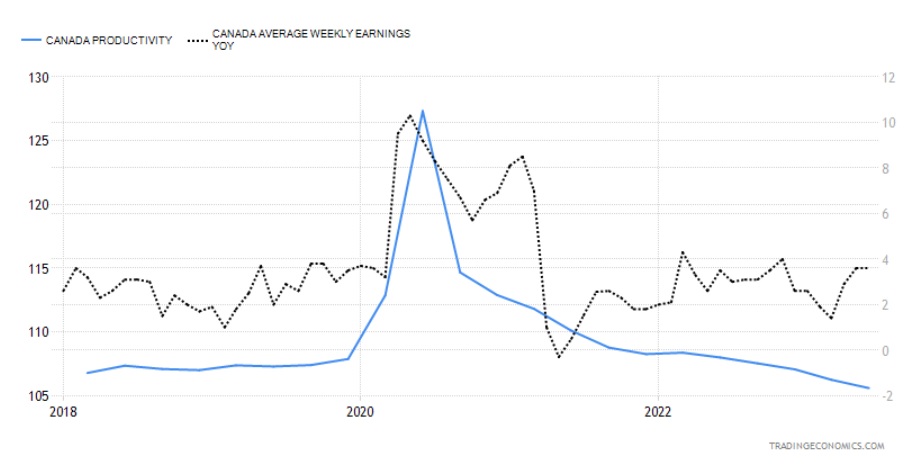

For example, labour is the most pervasive single cost in our economy. Last week we learned that average wages rose by 5.2% in August, up from 5.0% in July. Our productivity rate also continued to decline last month (see chart). No economist is arguing that inflation will return to target for as long as these well-established trends hold.

Energy prices probably comprise the second most pervasive (and visible) cost in our economy. Oil prices have now surged higher by 25% since their lows in June. Food prices are still lapping our inflation target and have increased by about 8% year-over-year according to our most recent CPI print (for July). The Loonie also just hit a two-year low, and that is stoking inflation by raising the prices of all imports.

Against that backdrop, a growing chorus of market watchers now argue that our 2% inflation target was too arbitrary and that a higher target, of say 3%, is more realistic. That line of thinking provides about as clear a signal as the BoC is ever going to get that higher inflation expectations are becoming entrenched.

My goal here is not to confidently predict what will happen next, but rather to question the confidence of others who are asserting that the BoC’s policy rate has now definitively peaked.

While I hope that will prove the case, the outcome is far from certain at this point. That means that anyone in the market for a mortgage today should proceed with caution.

At some point the most rapid series of rates hikes in the BoC’s history will combine with our record high household and government debt levels to slow the economy sufficiently that inflation will finally be reduced back to its 2% target. But we’re not close yet.

When we do reach that point, I expect the Bank to become very concerned about the economic damage it will have caused and to react by cutting its policy rate sharply. Variable-rate borrowers will stand to benefit immediately and significantly.

The risk, as is so often the case, will be in the timing.

If you can tolerate the risk that variable mortgage rates may go higher from here and remain at elevated levels for another year or more, choosing a five-year variable rate today has the greatest potential for saving.

If you instead value the peace of mind that fixed mortgage rates offer, I think a three-year term offers the optimal risk/reward balance today for conservative borrowers. They come with a premium of about .50% over current five-year fixed rates, but I would be reluctant to lock in for longer than three years when rates are peaking at their highest levels in more than a decade.

One- or two-year fixed rates are now about 1% higher than today’s lowest fixed rates, and the shorter the term, the greater the risk that you’ll be renewing before the BoC has won its inflation fight. If you’re willing to pay a premium for enhanced rate flexibility, I think variable rates are the better option.

The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields were range bound last week, holding at lower levels than their recent peaks. Some lenders responded by paring back their fixed rates by 0.05% or 0.10% (depending on the term).

Five-year variable-rate discounts were unchanged last week.

The BoC’s decision to hold steady last week was welcome relief for beleaguered variable-rate borrowers, but as per the analysis above, I think we should be wary of confident assertions that the Bank’s policy rate has now peaked.

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

September 11, 2023

Mortgage |

.jpg?width=883&height=328&name=Rate%20Table%20(September%2011%2c%202023).jpg)