In today’s post I focus on three economic signposts and explain how they inform my outlook for Canadian fixed and variable mortgage rates.

The Canadian economy is in the midst of being weaned off record levels of fiscal spending and the lowest borrowing rates on record. We are currently experiencing the highest inflation and the lowest unemployment rates in more than forty years as well as record high overall debt levels and house prices (at least for now).

Although this unusual current backdrop makes forecasting where rates are headed even more difficult than usual, there are some key signposts that can help us find our way.

In today’s post I’ll focus on three of those signposts and explain how they inform my outlook for Canadian fixed and variable mortgage rates.

1. Inflation

The Bank of Canada (BoC) is going to keep raising its policy rate until inflation starts to materially slow, so let’s start there.

Our headline Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose 8.1% in June. While that result marked its highest level since January 1983, it fell short of the consensus forecast of 8.4%.

Our overall CPI should begin to drop in the coming months because food and energy prices, which had been the biggest contributors to the recent surge, have started to move back down. In fact, somewhat surprisingly, oil and wheat prices recently dropped below their pre-Russian invasion levels.

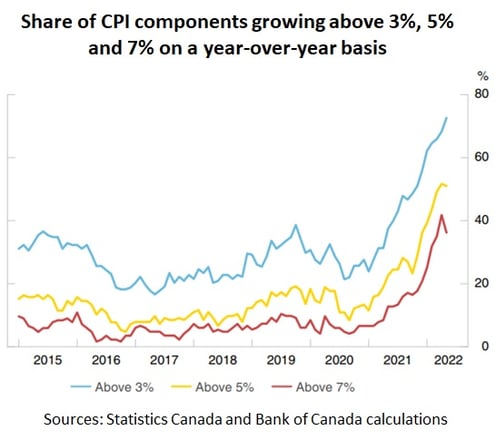

While the CPI components that experienced the sharpest increases are now reverting lower, their previous run ups caused a broadening out of inflationary pressures (see chart) that will make getting back to target more difficult and should keep the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) foot on the economic brakes over the near term, even as our overall CPI begins to drop.

Key Conclusion: Most observers will be focused on headline inflation, but the BoC’s core inflation measures are better gauges for the type of inflation the BoC is most concerned about.

2. Labour Costs

There is a lot of talk about price bubbles in just about everything these days, but from an inflation (and mortgage rates) standpoint, the most impactful of them all could well be the growing bubble in labour prices, which may soon become the most significant driver of inflationary pressures.

When COVID first hit, our federal government focused its emergency stimulus payments on enabling businesses to keep workers at least marginally attached to their jobs. That decision shortened the time it took for our economy to recover all the jobs that were lost in the pandemic, but has it led to better outcomes over the longer term?

By way of comparison, while the US economy took considerably longer to fully recover its lost jobs, its GDP recovered much more quickly than ours, and I don’t think that was a coincidence. Many Canadian companies over-employed relative to their actual labour needs, as evidenced by our steady drop in labour productivity since the start of the pandemic. That misallocation created a shortage of labour available for new hiring and prevented our economy from more efficiently retooling into its new, post-pandemic form.

The artificial labour shortage brought on by over-employment also led companies to hoard staff and hire pre-emptively in anticipation of future shortages. This is exactly the kind of self-fulfilling prophecy that the BoC fears may occur with inflation itself, where fear of inflation begets actual inflation.

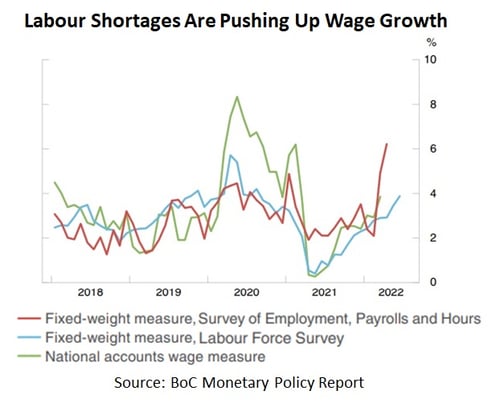

While labour costs are rising steadily now, they still aren’t keeping pace with inflation, and that means the purchasing power of the average Canadian continues to shrink. But our record low unemployment is also giving employees increased negotiating power, even those who aren’t part of collecting bargaining groups. That is now driving up the most fundamental, and likely the stickiest, of all costs (see chart).

While it is a delicate topic for our policy makers, when they talk about the need for “pain” to bring inflation to heel, they aren’t just talking about our real-estate markets. Reducing labour demand to reduce inflationary wage pressures is also high on their list.

Key Conclusion: Raising rates to materially reduce labour demand will likely require more rapid tightening over the short-term. But that, in turn, will also increase the odds that a hard landing and subsequent rate cuts will follow.

3. The US Federal Reserve’s Latest Rate Hike

Last week, the US Federal Reserve hiked is policy rate by 0.75% for the second straight month, to a range of 2.25% to 2.50%, marking its sharpest increase in more than forty years.

The Fed will likely have to hike its policy rate by more than the BoC over the duration of their current tightening cycles. US inflation is currently higher (9.1% vs 8.1% in Canada), and the US has a much lower household debt-to-income ratio, making its economy less sensitive to rate rises. For those reasons, the Fed’s rate-hike path will likely serve as the upper boundary for anyone trying to deduce where the BoC’s policy rate is headed.

On that note, at his accompanying press conference, Fed Chair Powell said that a range of 3.4% to 3.8% is his current best guess of where its policy rate will top out. For its part, the US bond futures market is currently pricing in 0.75% in Fed rate cuts after the Fed’s policy rate peaks, in the belief that its hikes over the remainder of this year will slow the US economy by more than expected.

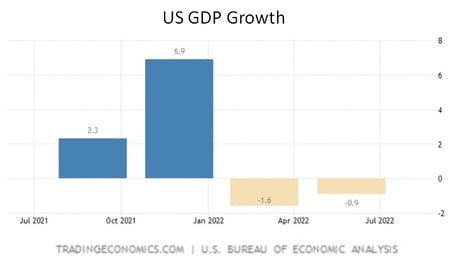

Powell also said that future rate hikes would not follow any largely predetermined path but will instead be “data dependent”. Investors interpreted that as a signal that the Fed’s hiking pace will slow because US economic momentum is already sputtering (see chart). The US bond futures market is now pricing in a 0.50% hike by the Fed at its next meeting in September (down from the 0.75% raise that was priced in prior to last week).

I don’t view the Fed’s latest guidance the way the bond market does.

The Fed emphasized that it remains “highly attentive to inflation risks” and remains “strongly committed to returning inflation to its 2 percent objective”. Fed Chair Powell also conceded that achieving that end may require “some softening in labor market conditions” and weaker economic growth for a “sustained period”. It certainly sounds to me as though the Fed is willing to sacrifice growth, and risk recession, if that is what it will take to bring US inflation back down to its 2% target.

Key Conclusion: The Fed still sounds determined to continue hiking its policy rate over the near term, but just as with the BoC, I think that will increase the odds of an eventual hard landing and consequent rate cuts thereafter.

The Bottom Line: The five-year Government of Canada (GoC) bond yield dropped by another 0.26% last week and is now down almost 1.00% from its recent peak in mid-June. Lenders have started to drop rates, but as is often said, they “take the elevator” on the way up and “take the stairs” on the way down.

Also, fellow mortgage broker Rob McLister tweeted last week that RBC’s borrowing cost is “up about 90 bps [basis points] year-to-date”. Higher funding costs mean that lenders will require wider spreads than usual, but even then, five-year fixed rates should continue to fall from their currently available levels if the five-year GoC bond yield holds steady.

Five-year variable discounts were unchanged last week. I think variable-rate borrowers should expect additional rate hikes over the remainder of 2022, but for the reasons outlined above, I expect the BoC and the Fed to follow with rate cuts in 2023.

Image Credit: iStock/Getty

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

August 4, 2022

Mortgage |

.jpg?width=883&name=Rate%20Table%20(August%201%2c%202022).jpg)