Is the Bank of Canada shifting away from rates staying ultra low - and should mortgage borrowers lock in now?

The Bank of Canada (BoC) and the bond market have been in a fight about where inflation and interest rates are headed.

Until last week, the Bank predicted that neither would rise sustainably for years to come. BoC Governor Macklem told us to prepare for a “tough slog” and warned that it would be a “long climb back” to full recovery. Against that backdrop, last November, he said that “Canadians can be confident that borrowing costs are going to remain very low for a long time”.

Bond-market investors disagreed.

The market consensus subscribed to the view that when the pandemic ends, consumers will unleash their pent-up savings and trigger a flood of demand that will drive inflation higher and force the BoC to raise its policy rate sooner than forecast. Recent improvements in our economic data and our economy’s resilience during the second-wave lockdown have helped to bolster that belief.

It is rare to have such open disagreement between our central bank and the bond market. Eventually, one has to come around to the other’s view, and last week, the BoC appeared to do just that.

It had previously estimated that keeping rates low for “a long time” would mean holding its policy rate at 0.25% until sometime in 2023. But in last week’s more optimistic policy-rate statement, the Bank moved up its timetable and predicted that its next rate hike would now likely come “sometime in the second half of 2022”.

The BoC also announced that it would taper its quantitative easing (QE) programs, effective immediately, by reducing its weekly net purchases of Government of Canada (GoC) bonds from $4 billion to $3 billion.

(As a reminder, the BoC has used QE to purchase massive amounts of GoC bonds. This helps reduce their yields, and by association, the fixed mortgage rates that are priced on them.)

The market’s initial reaction was as one would expect.

Our current extended period of ultra-low rates has exacerbated fears that at some point they will move inexorably higher.

It wasn’t long before the usual pundits took to their pulpits to warn variable-rate borrowers to lock in today’s fixed rates while they still can. (Interestingly, those same commentators have sounded the alarm so many times that anyone following their advice would have already done so long ago.)

If you’re looking for more support for the consensus view, you won’t find it in this post. Instead, here are five contrarian observations relating to last week’s BoC update:

- The Bank threaded the theme of uncertainty into every stitch of its forecast.

The BoC may have taken a hawkish turn, but it also made sure to leave plenty of room to change its mind again if and as circumstances warrant. Here are some examples:

- “Considerable uncertainty surrounds the medium-term outlook for GDP and potential output”, and “… estimates of when the output gap will close are particularly uncertain.”

- “The uncertainty around the inflation outlook is greater than usual.”

- “Since January, some upside risks associated with the ability to limit the impacts of the virus have been realized and are now embedded in the base-case projection. As a result, pandemic-related risks are now skewed to the downside.”

- BoC Governor Macklem: “We won’t count our chickens before they hatch” and we will wait until the recovery is “complete”.

- And my new personal favourite disclaimer for time-based forward guidance: “Our forward guidance is not calendar based, it’s outcome based.”

A forecast rife with that many qualifiers isn’t guidance, it’s a guess.

- The BoC needed to create some interest-rate uncertainty in order to rein in housing markets.

When the pandemic was still in its early days, the BoC was worried about an economic collapse akin to an outright depression. Although it knew that its lower-rates-for-longer guidance would stimulate housing activity, that was a risk it was willing to take.

BoC Governor Poloz acknowledged his thinking at that time when he recently said, “We cut interest rates in order to boost the economy. Well, if we’re not going to have a hot housing market, we won’t have any reaction at all to [low rates], and so that’s all part of the side-effect of the job you’re there to do”, before adding, “If the side-effect is a hot housing market, that’s one I’ll take every day.”

That’s how we ended up where we are today, with skyrocketing house prices and bidding wars in every city and town.

The BoC had to do something.

Our banking regulator recently announced a small increase to the stress-test rate for uninsured mortgages, and our federal government included a foreign home-buyers tax in its budget, but those tweaks won’t be enough to slow runaway real-estate momentum that is primarily underpinned by the low-rates-forever mentality the BoC spawned.

In its latest statement the Bank acknowledged “the potential risks associated with the rapid rise in house prices”, and BoC Governor Macklem highlighted the danger that what started out as “fundamentals-based behaviour” could evolve into “speculative, extrapolative behaviour”.

That’s the point where buying decisions are based on the belief that the current conditions of rock-bottom rates and rapidly rising prices will continue indefinitely.

By moving up its rate-hike guidance, the BoC just poured some water into the punch bowl.

- The BoC isn’t going to raise rates ahead of the US Federal Reserve.

Even if the BoC’s latest forecast of a more rapid and resilient recovery proves correct, the simple fact remains that it isn’t going to hike its policy rate ahead of the US Federal Reserve – and the Fed continues to predict that its next hike will not be until early 2024.

The BoC’s new optimism is based in part on its belief that “strong growth in foreign demand” will lead to a “robust recovery in exports and business investment”.

Long-time readers of this blog will recall that’s the same robust recovery in exports and business investment that the Bank has been calling for … and waiting for … since the Great Recession.

The Loonie’s appreciation against the Greenback (and other currencies) since the start of the pandemic is already exerting a drag on our economic momentum, which the BoC refers to as “competitiveness challenges” (see chart).

In its latest Monetary Policy Report (MPR) the Bank noted that “the US dollar has strengthened against the currencies of most US trading partners since the January Report and the Canadian dollar has appreciated by about 1 percent against the US dollar.”

In other words, most of the countries we compete with for US demand have seen their currencies weaken against the Greenback, but the Loonie has risen against it instead (and that was before the BoC moved forward its rate-hike timetable).

The chart below shows what the Loonie did on Wednesday, right after the BoC released its latest policy statement. Keep in mind this was a reaction to what the BoC merely speculated it might do more than a year from now. If the Bank were to actually follow through on its plans to front-run the Fed, the currency market’s reaction would be much more severe.

It’s hard to imagine a rationale for the BoC raising its policy rate ahead of the Fed. The US recovery is much farther along, US vaccination rates put ours to shame, and the US federal government is just as fond of stimulus as is ours.

While our jobs recovery has outpaced the US recovery thus far, a BoC rake hike would cause the Loonie to soar against the Greenback. That happened during the Great Recession and it destroyed large swaths of our export sector that never recovered.

There is no way the Bank will repeat that mistake this time around.

- The BoC had to taper its QE purchases.

The Bank positioned its decision to taper its weekly QE purchases from $4 billion to $3 billion as a natural by-product of our recovering economy’s reduced need for stimulus, but it shouldn’t be lost on anyone that it was also compelled to slow its GoC bond purchases after having already taken so many of them out of circulation.

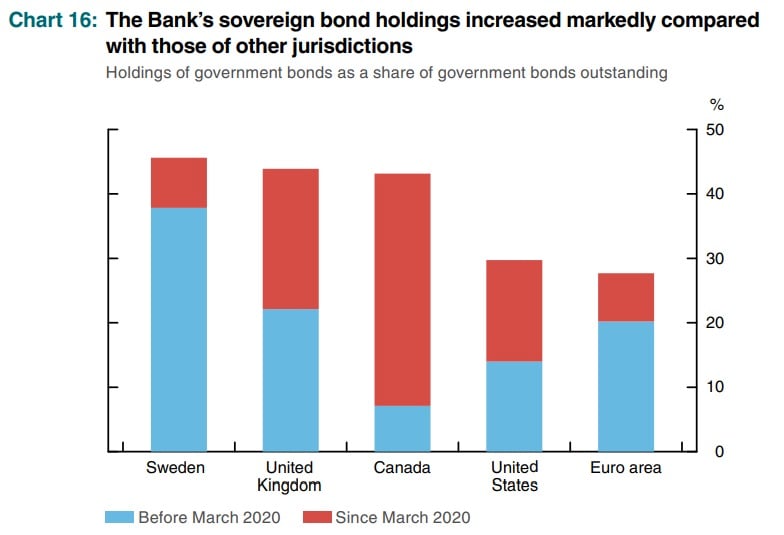

The BoC estimates that today it owns about 42% of the total GoC bonds in circulation and it is generally agreed that if that total were to hit 50%, there wouldn’t be enough supply left to ensure adequate market liquidity.

By its own admission, the Bank has engaged in proportionately more QE than any other central bank since the pandemic began, as the chart below from its latest MPR shows.

There is no denying that our financial system was stabilized, in part, by the many emergency measures put in place by the BoC when the crisis first hit. And we should all be encouraged that normal market functioning has resumed to the point where the Bank feels confident enough to begin the process of removing those supports. But in this specific case, the BoC was actually compelled to taper its QE purchases for liquidity reasons. Tying that move to improving market conditions was just spin.

- Higher inflation doesn’t mean rates are going to the moon.

If the BoC’s new economic forecasts prove correct, we still aren’t likely to end up with the kind of inflation that keeps some borrowers up at night.

The Bank continues to predict that our current inflation run-up will prove transitory and attributes it to “the fact that the prices of some goods and services fell sharply with the sudden drop in demand at the onset of the pandemic”. Those same prices are now normalizing, and that normalization process pushed our overall Consumer Price Index (CPI) to +2.2% in April.

The BoC forecasts that inflation will drop back below its 2% target in 2022 before rising above 2% in 2023 if, as it forecasts, consumption, investment and exports all surpass their pre-pandemic levels and our overall momentum becomes “broad-based and self-sustaining”.

Much has to go right for that scenario to unfold, but if it does, what then?

Today’s high debt levels ensure the BoC won’t have to raise rates by as much as in past cycles to slow the economy and bring inflation to heel. Also, coming out of the current crisis, the Bank will likely be cautious when it next raises rates, allowing time for our economy to absorb the impact and to observe its effects. These combined factors portend a slow, gradual rate-hike cycle to come.

If you’re deciding between a fixed and a variable rate today, you’re probably looking at a variable rate that is about 0.75% lower than its fixed-rate equivalent. Even if the BoC does start raising its policy rate in the second half of next year, that buffer means that you will continue to save money with every payment until the BoC’s policy rate rises from 0.25% to 1.25%.

Based on that, and although it cannot be guaranteed, I still think variable rates will produce a net saving.

(Remember also that variable-rate mortgages provide the option to convert to fixed rates at any time, and to ensure further protection against rate rises, I also recommend that variable-rate borrowers set their monthly payments to what they would have been had they chosen a higher fixed rate instead. That will accelerate principal repayment and create a cash-flow buffer from the outset.)

To be clear, anyone who chooses a variable rate today should be prepared for it to rise over the next five years. If that realization will deprive you of a good night’s sleep, choose a fixed rate instead. But if you can live with its inherent risk, I continue to believe that variable rates will save money over their fixed-rate equivalents for the next five years.

After such a long period of ultra-low rates and soothing forward guidance, even the possibility that your rate may rise at some point farther down the road can feel like a major shift.

Which, probably, is just as the BoC intended.

The Bottom Line: The five-year GoC bond yield that our five-year fixed mortgage rates are priced on barely budged last week, despite all of the commotion surrounding the BoC’s shift in guidance, the release of the federal budget, and Statistics Canada’s announcement that our April CPI came in at 2.2%.

If last week didn’t move the needle, there is nothing on the near horizon that likely will, and that means that our fixed mortgage rates should remain range-bound for the time being.

Meanwhile, variable rates were unchanged last week, and according to the BoC, they aren’t expected to rise until sometime in the second half of 2022.

Image credit: iStock/Getty Images

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

April 26, 2021

Mortgage |

.jpg?width=687&name=Rate%20Table%20(April%2026,%202021).jpg)