After years without rate increases, variable rate borrowers may soon see an increase for the fifth time in a row - is it time to lock into a fixed rate?

Last week we learned that our overall inflation rate, as measured by our Consumer Price Index (CPI), increased by 2.8% on a year-over-year basis in August.

While that result marked a slight decrease from our CPI growth rate of 3% in July, it was still well above the Bank of Canada (BoC) target rate of 2.0%. Also, the BoC’s three key measures of core-inflation, which are designed to smooth out short-term spikes in volatile CPI inputs, like energy, all came in at 2.0% or higher last month.

Not surprisingly against that backdrop, the bond market is now assigning about 90% odds that the BoC will raise its overnight rate, which our variable mortgage rates are priced on, when it next meets on October 24.

If the BoC raises its policy rate by another 0.25% as expected next month, it will mark the fifth quarter-point increase for existing variable-rate borrowers in the last fifteen months. That’s quite a contrast to the seven years prior to that period, when the Bank didn’t raise rates a single time. Understandably, many variable-rate borrowers are starting to wonder if now is a good time to pull their conversion parachute cords and switch to a fixed rate.

Bluntly put, we’ll only know in hindsight if this is the right call for each borrower, for the obvious reason that no one can predict the future with certainty, but also because the spread between a borrower’s existing variable rate and their available fixed-rate alternatives will vary.

That said, if you’re a variable-rate borrower trying to decide whether to lock in now, here are my thoughts on how things may play out over different periods of time.

Over the longer term, I think the BoC would like to continue raising rates, but only when it feels that our economic momentum can withstand the additional tightening.

Our overnight rate is currently 1.50%, and that’s still not far from the 0% floor that we hit at the peak of the Great Recession. At 0%, the Bank’s ability to stimulate our economy is greatly diminished because it can’t lower rates any further. That means its only option is to rely on unconventional (and riskier) monetary-policy tools like quantitative easing (QE). (Reminder: Unlike most of the world’s largest central banks, the BoC didn’t resort to QE during the financial crisis.)

The higher the overnight rate, the more room the Bank has to lower it when the next downturn hits, so each additional rate hike returns another arrow to the BoC’s quiver.

The BoC estimates that its neutral rate, which is defined as the policy rate that is “consistent with output holding at its potential level and inflation holding at target on an ongoing basis”, is currently between 2.5% and 3.5%. All else being equal, if the BoC believes that the bottom end of our neutral-rate range is currently 2.5%, this implies that the Bank needs to continue moving its overnight rate higher over time. (Important note: the neutral rate range is based on a wide range of factors that vary, like demographics, so it changes over time.)

On a related note, the BoC knows that extended periods of ultra-low interest rates can fuel inflation that isn’t captured in CPI or core inflation data, such as the inflation in real-estate and other asset prices that we have seen since the start of the Great Recession. And the longer rates stay at stimulative levels, the greater the risk that speculative bubbles will form.

Over the nearer term, our recent spike in CPI inflation is cause for more immediate BoC concern. The Bank’s mandate is to promote our economic welfare by using its monetary policy to maintain price stability, which is defined as maintaining an overall inflation rate in a range between 1% and 3%, and ideally, at a target rate of 2.0%. Given that, while the BoC has said that it expects our current inflation rate of 2.8% to revert to about 2% in the early part of 2019 when temporary, outsized impacts from volatile factors like spiking gasoline prices dissipate, it may be inclined to raise rates further to help ensure that outcome.

There are other additional signs of rising inflationary pressure over the near term. Our unemployment rate hovers at 6.0%, very near its lowest level in forty years, and recent BoC business surveys confirm that companies are struggling to meet demand as they grapple with the strongest capacity constraints that they have seen since before the Great Recession.

If all of this is making you want to run out and convert your variable-rate mortgage, hold on just a little longer.

The BoC’s monetary-policy does not exist in a vacuum. The impacts from its rate hikes are both far reaching and slow to materialize. The Bank has to account for the risks that tightening monetary policy too quickly could tip our economy into recession, trigger a wave of debt defaults and/or set off a sharp and destabilizing decline in real-estate prices. If the BoC isn’t careful, its prescribed remedy (higher rates) could end up having a more harmful impact on our economy than the disease (higher inflation).

The most critical factor staying the BoC’s hand at the moment is NAFTA uncertainty. Without knowing how our ongoing trade negotiations with the U.S. will play out, the Bank can’t risk leaning too far over its ski tips.

If the trade negotiations lead to more tariffs, that will stoke inflationary pressures and could cause the Bank to accelerate its rate hike timetable over the short term. But if that happens, it will be because the negotiations aren’t going well and if that is the case, ongoing trade frictions are likely to dampen our economic growth rate and correlate with lower policy rates over the longer term.

If the NAFTA negotiations with the U.S. come to a positive resolution (which is an outcome that will itself take time to assess), the consensus believes that the BoC will accelerate its rate-hike timetable. But that view discounts another potentially concurrent risk – that of a U.S. recession.

The U.S. federal government cut taxes last December and launched new stimulus spending in February. These moves were unprecedented for an economy that was already operating at or even above its full capacity, and they have forced the U.S. Federal Reserve to increase the pace of its rate hikes in an effort to stay out in front of rising U.S. inflationary pressures. (Several of the experts I read regularly believe that history will judge the U.S. federal government’s recent fiscal actions as the worst economic blunders of the modern era.)

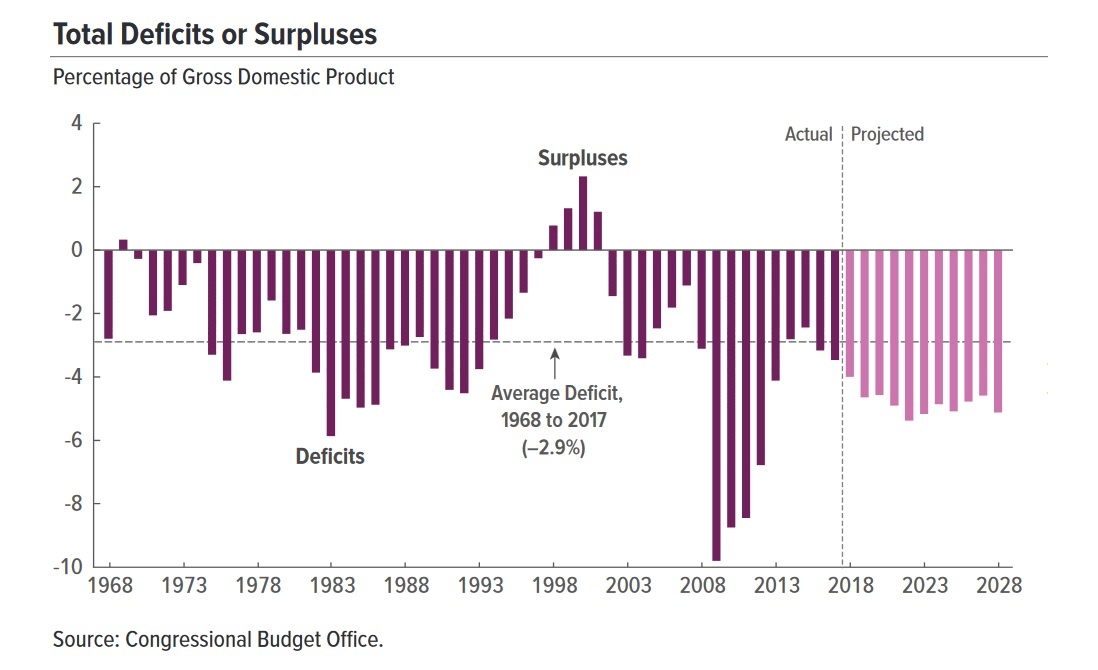

The Fed is also expected to raise its policy rate by another 0.25% when it meets this week, and that will mark its eighth rate hike since the end of 2015. Each additional Fed increase hastens the arrival of the next U.S. recession, and when it hits, the U.S. Federal Government’s budget deficit, which is already at recession-era levels (see chart below), will limit the government’s policy options for a response. That has the potential to increase both the severity and the duration of the next U.S. recession, and it also raises the risk that it will work its way north of the border.

While I think the BoC wants to continue raising its overnight rate in the near term and has an upward rate bias over the longer term as well, that still doesn’t guarantee that our variable mortgage rates will prove more expensive than their fixed-rate equivalents over time. Here are a few reasons why I say that:

- The BoC has repeatedly said that it will take a cautious approach to additional rate hikes and that it can take up to two years for the impact of past hikes to fully work their way through our economy. The longer it takes for the BoC to raise rates, the more savings will accrue to variable-rate borrowers.

- The Bank doesn’t think that it will have to raise rates by as much as it has had to in past cycles because our elevated household debt levels magnify the impact of each additional rate hike (and we’re already four rate hikes into this tightening cycle).

- Each additional rate hike creates a headwind for business investment and exports, which the BoC is hoping will underpin growth during the next phase of our economic cycle.

- Rates don’t rise during a recession. Of course that isn’t a reason to hope that we have one because lower rates would be only a silver lining on otherwise cloudy economic days ahead. I think a U.S. recession is coming in the relatively near future and when that happens, the U.S. Fed will either move to the sidelines or resort to rate cuts. If it does, I expect the BoC to follow.

Lastly, while all the talk of late has centred around the likelihood and timing of additional BoC rate hikes, it’s also important to remember that there hasn’t been a single five-year period in the last twenty-eight years when variable-rate borrowers didn’t see at least one rate cut over their five-year term. That’s worth keeping in mind if you are worrying that your variable rate can only ratchet higher in the years to come.

The Bottom Line: I expect Canadian variable mortgage rates to rise by another 0.25% over the near term, but after that, for the reasons outlined above, I think the odds of more hikes decrease significantly. Over the medium and longer terms, while the BoC sounds inclined to continue raising rates if possible, it has repeatedly said that it would do so cautiously. I think a coming U.S. recession will lead to slower growth in Canada that will raise the possibility of rate cuts thereafter. If you can stomach the volatility, there may well be some saving in variable rates yet.

Top Image Credit: vladwel

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

September 24, 2018

Mortgage |

.jpg?width=600&name=Rate%20Table%20(September%2024,%202018).jpg)