The Bank of Canada just got another reminder about the perils of offering forward guidance.

When the Bank (BoC) released its most recent policy statement in early June, it might as well have hung out a neon sign that said, “We’re hiking rates at our next meeting in July”.

Then Murphy’s law kicked in and just about every ensuing economic development from that point forward served to undermine the BoC’s intent. To wit:

- U.S. President Donald Trump slapped tariffs on imports of Canadian steel and aluminium the same day the BoC issued its latest policy statement. Then he launched a slew of personal insults at Prime Minister Trudeau and threatened to place tariffs on Canada’s automotive exports to the U.S. (In addition to going after the G7, President Trump also slapped $50 billion worth of tariffs on Chinese imports, and China quickly responded in kind, setting the stage for a trade war between the two global economic super powers.) The BoC has repeatedly emphasized that it will be cautious in the face of uncertainty, and with President Trump’s latest antics undermining the ongoing NAFTA negotiations, the future of our most important trading relationship is now more uncertain than ever. I don’t see the BoC raising its policy rate against that backdrop unless it feels that rising inflationary pressures leave it with no choice (more on that below).

- Shortly after the BoC’s announcement, Statistics Canada released our latest employment data and it showed that our economy lost an estimated 7,500 jobs in May. That means that we have now lost nearly 50,000 jobs, on a net basis, since the start of 2018. The detail in last month’s data wasn’t any better: the number of jobs for prime working-age Canadians (aged 25 to 54) declined, the manufacturing sector lost another 18,000 jobs, and the participation rate, which measures the percentage of working-age Canadians who are either employed or actively looking for work, dropped again as more people gave up looking for work altogether. The one bright spot was that average wages rose in May, but minimum wage increases in Ontario and British Columbia have partially (and only temporarily) skewed that measure. The current lack of job-market momentum should help to keep a lid on labour costs over the near term and allow the BoC more time for caution, if it is so inclined.

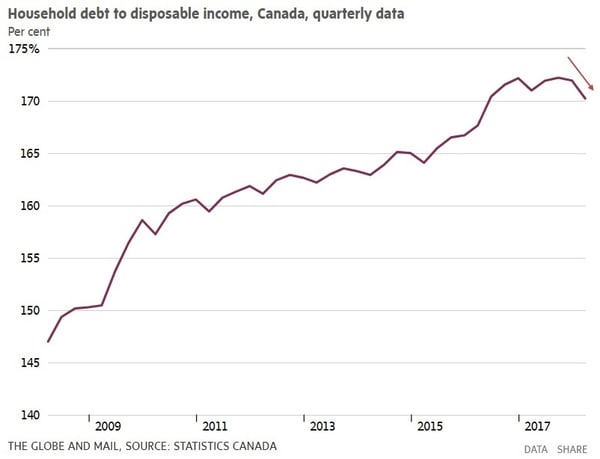

- In mid-June we received confirmation that our rate of household debt accumulation slowed over the first quarter of this year. Mortgage borrowing declined by $2 billion and returned to mid-2014 levels. This development served as confirmation that the BoC’s previous three rate hikes, combined with the latest round of mortgage rule changes, are achieving their desired impact. Statistics Canada also confirmed that our household debt-to-disposable-income ratio saw its biggest quarter-to-quarter decline in the 28 years that this measure has been tracked (as reported in the Globe and Mail). These developments should help allay the BoC’s concerns that its current policy rate is stimulating excessive borrowing (see chart below).

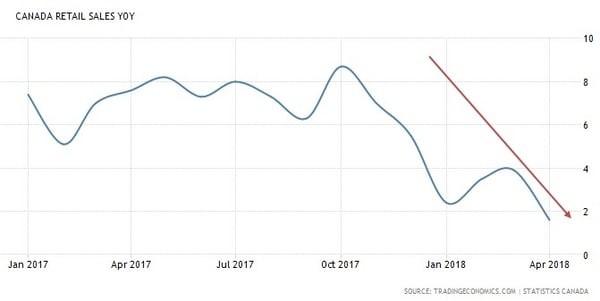

- Last Friday we learned that retail sales fell 1.2% last month, below the flat reading the consensus had predicted. The biggest drop was in car sales, but eight of the eleven retail sales subsectors saw declines last month, so there was weakness across the board. The BoC’s most recent forecasts have assumed that consumer spending will prove resilient, but the retail sales data imply otherwise (see chart), and additional rate hikes are certainly not going to help in that regard.

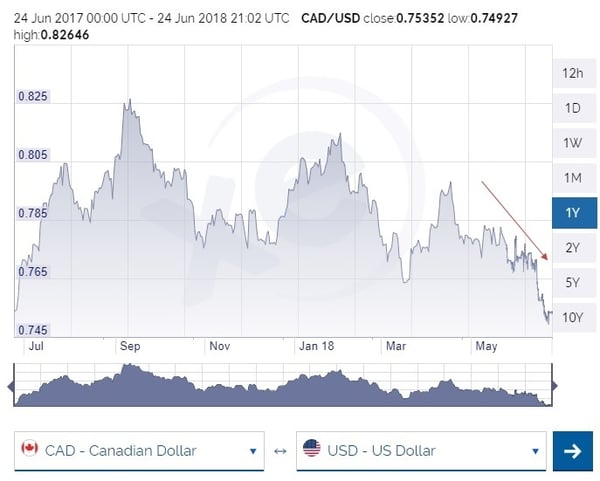

- The Loonie’s value has stayed stubbornly high versus the Greenback for some time now and the BoC has repeatedly expressed concern about the “competitiveness challenges” that this has created for our exporters. Then, very recently, the Loonie began to fall, trading down to 75 cents versus the Greenback by last Friday and bringing our beleaguered exporters some much needed relief. If the BoC raises its policy rate at its next meeting on July 11, the Loonie’s recent fall may reverse (and while the BoC likes to say that it doesn’t account for currency fluctuations when making policy decisions, experienced market watchers know better). On a related note, while it is true that a weaker Loonie will itself be inflationary because it will increase the costs of our imports, the BoC has typically looked through this temporary impact.

While the points made above support the BoC holding off on a rate increase at its next meeting, the Bank’s primary mandate is to keep inflation “low, stable and predictable” and it won’t hesitate to raise its policy rate if it becomes concerned about significantly rising inflationary pressures. On that note, our overall inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), has been slightly above its 2% target since February, and the three key inflation sub measures that the Bank relies on have been right around their 2% targets since the start of 2018.

Not surprisingly, the BoC’s policy-rate language has become more hawkish over that period. And as the Bank’s concerns about rising inflation have increased, so too has the importance of new inflation data.

To that end, last Friday Statistics Canada released our latest inflation statistics for May, and we learned that our overall CPI rose by 2.2% on a year-over-year basis last month, well below the 2.6% that the economist consensus had forecast. (Our month-over-month increase came in at 0.1%, which was also well below the consensus forecast of .04%.) Meanwhile, each of the BoC’s three key inflation sub measures stayed flat or declined (each now stands at 1.9%), and core inflation, which strips out more volatile price inputs like food and energy, fell from 1.5% in April to 1.3%.

If rising inflationary pressures were on the verge of forcing the BoC to raise its policy rate when other economic measures, along with rising trade uncertainty, were making it less inclined to do so, the latest inflation data may have altered that balance. The Bank is more likely to exercise caution (and restraint) if it believes that inflationary pressures are moderating on their own now and especially when other data corroborate that conclusion (as I believe they do).

The bond futures market seems to share that view. Globe and Mail writer David Parkinson recently noted that overnight index swaps have moved the odds of a BoC rate increase in July from 80% down to 50%.

The Bottom Line: The BoC’s plan to raise its policy rate at its next meeting in July has been undermined by U.S. President Trump’s trade-war antics and by our weakening economic data. Those developments may cause the BoC to adopt a more cautious approach, which it can better afford now that household debt accumulation is slowing, and most importantly, if it believes that inflationary pressures are levelling off. Those underlying factors may only delay our next rate hike until the fall, but they also decrease the likelihood that we will see multiple rate increases on the near horizon, and that should give some comfort to variable-rate borrowers.

Top Image Credit: Zdenek Sasek, Getty Images

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

June 25, 2018

Mortgage |

.jpg?width=600&name=Rate%20Table%20(June%2025,%202018).jpg)