Why it is unlikely that the the Bank of Canada will raise the rates that affect our mortgages ahead of its US counterpart.

Anyone trying to figure out where Canadian mortgage rates are headed should be keeping a close eye on the US Federal Reserve.

We sell about 80% of everything we export into US markets, and about 50% of our total imports come back the other way.

This extensive trade relationship with a country whose GDP is more than ten times our own explains why our Government of Canada (GoC) bond yields, which our fixed-mortgage rates are priced on, tend to move in lockstep with their US equivalents.

In addition, our broad and deep economic ties also severely limit the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) ability to deviate its policy rate, which our variable mortgage rates are priced on, from the Fed funds rate (which I detailed in this recent post).

At the moment, the BoC is forecasting that it will raise its policy rate some time in the second half of 2022, but that prediction is based in large part on the assumption that our economy will be buoyed by an export-led recovery.

The US Federal Reserve has sounded much more cautious about the timing of its next rate hike, and while its guidance is less explicit, it is widely assumed that the Fed doesn’t expect to raise its policy rate until late 2023.

If the BoC does front-run the Fed, the Loonie will likely soar against the Greenback and inhibit our export sector’s momentum. Given that, and despite the fact that you will never hear the BoC concede this point, I continue to believe that it is unlikely that it will raise ahead of its US counterpart.

On that note, the Fed met last week and offered an updated assessment of current US economic conditions via its latest policy statement and Fed Chair Powell’s accompanying press conference commentary.

Here are five highlights that shed light on the Fed’s anticipated rate-hike timetable.

1. Pandemic progress

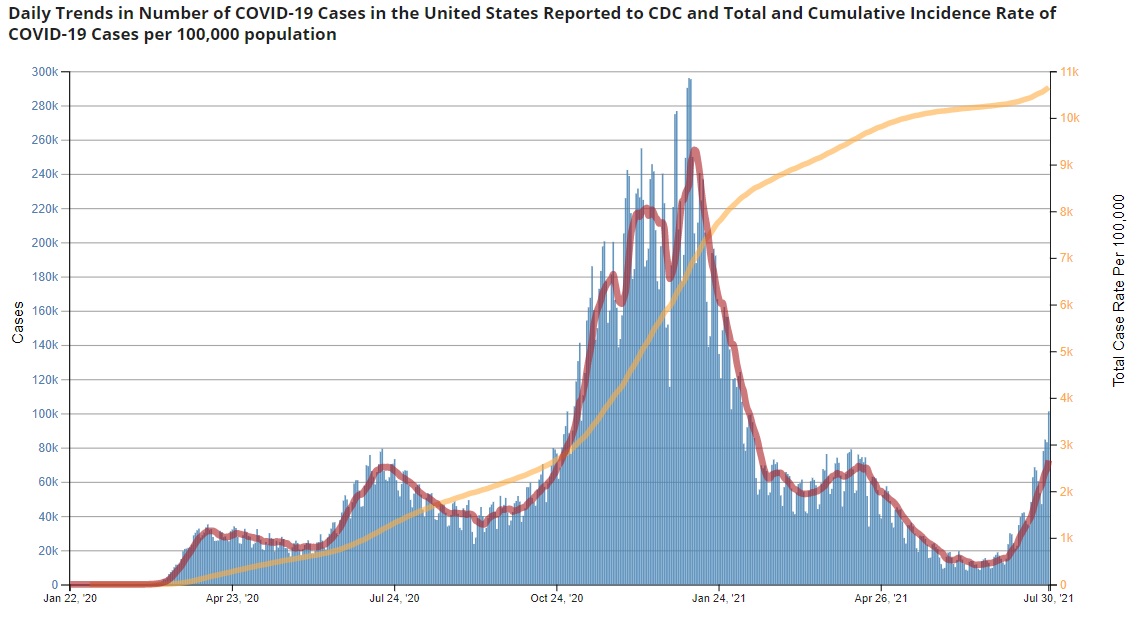

The Fed noted that “progress on vaccinations will likely continue to reduce the effects of the public health crisis on the economy”, but Fed Chair Powell also observed that “the pace of vaccinations has slowed, and the “delta” strain of the virus is spreading quickly in some areas”.

The chart below illustrates the recent infection increases.

2. The current US inflation backdrop

In its policy statement, the Fed reiterated its goal of achieving average inflation of 2% over the long term and noted that because it has come in “persistently below this longer-run goal” for most of the pandemic, inflation would be allowed to run “moderately” above 2% “for some time” going forward.

It also acknowledged that “inflation has risen” (to 5.4% in June) but continued to attribute the run-up to “transitory factors”.

Fed Chair Powell assessed that demand has recovered more quickly than supply and conceded that inflation may now remain elevated for longer than previously forecast. But he then reiterated the Fed’s belief that it will moderate once supply constraints are rectified and price normalizations return to their pre-pandemic levels (and work their way through the inflation data).

Powell also observed that the current inflation surge is not being caused by a broad rise in prices but can instead be attributed to “a handful of specific factors” and that each “has a story … [that] is really about the reopening of the economy”. He acknowledged the concerns of bond-market investors that the near-term risks to inflation are to the upside but expressed confidence that the temporary factors driving prices higher would sort themselves out over time.

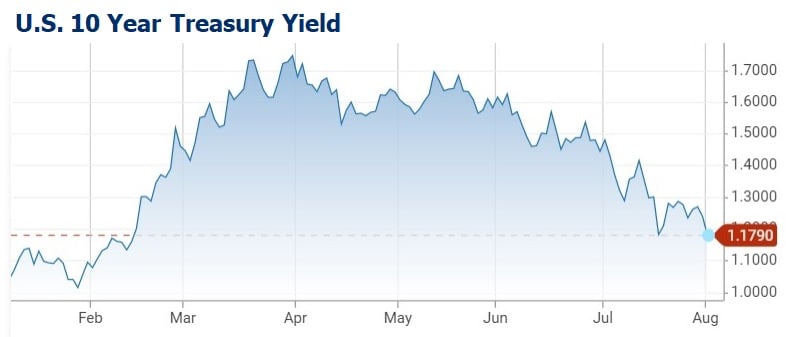

The bond-market consensus now appears to be coming around to the Fed’s view that the current inflation run-up will eventually subside. US bond yields that spiked earlier this year have fallen steadily since June (see chart below).

3. The US employment recovery

The Fed noted that while employment has “continued to strengthen … the sectors most adversely affected by the pandemic … have not fully recovered”.

The Fed had previously committed to maintaining its ultra-accommodative monetary policies until the US employment recovery shows “substantial further progress”. In his press conference, Fed Chair Powell noted that “we are some way away from having had substantial further progress.”

Powell assessed that the official US unemployment rate of 5.9% understates the current shortfall in jobs because the participation rate has not recovered much from its lows last year. (As a reminder, the participation rate measures the total percentage of working-age Americans who are either working or actively looking for work.)

When asked about the current employment data anomaly that shows 9.5 million unemployed workers alongside 9.2 million job openings, Powell acknowledged those concurrent statistics as “unusual” and attributed them to temporary factors related to the pandemic. He also predicted that there would be “a speed limit” on how quickly that anomaly would be resolved, because rehiring would take time and because of skills mismatches.

4. When the Fed will reduce its quantitative easing (QE) programs

The Fed has been using QE to purchase $80 billion worth of US Treasury bonds and $40 million worth of mortgage-backed securities each month. This has helped to suppress US yields, and, by association, their GoC equivalents.

Some market watchers expected the Fed to hint at tapering its QE programs at this meeting, but that didn’t happen.

Instead, Powell concluded that “we have not reached substantial further progress yet” and reiterated that the Fed wouldn’t taper until the US economy has made “substantial further progress” towards achieving “maximum employment” and keeping inflation “on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time”.

On a related note, Powell was also asked if the Fed would wait until it had ended its QE programs altogether before raising its policy rate.

He responded that while there was no hard-and-fast rule, it would make sense for the Fed to end QE before starting to raise rates to avoid pitting the two policies against each other (because QE is a form of policy easing and rate hikes are a form of policy tightening).

5. When the Fed will raise its policy rate

Fed Chair Powell bluntly assessed that the Fed is “clearly a ways away from considering raising interest rates”.

He added that “lift off”, which is a term used to describe the point at which the Fed begins to raise its policy rate, is “not something that is on our radar screen”.

In summary, the Fed maintained its dovish stance last week and, based on the recent path of bond yields, appears to have won its fight with the bond market about whether the current US inflation run-up will end up being transitory (at least for now).

For my part, I continue to believe that the Fed’s continued slow-and-steady approach will limit the BoC’s lift-off plans and that both our fixed and variable mortgage rates are likely to fall slightly as the Roaring 20s narrative, which used to be the be the market consensus, continues to fade in the rear-view mirror.

.jpg?width=687&name=Rate%20Table%20(August%202%2c%202021).jpg)

The Bottom Line: Five-year fixed rates held steady last week, but the five-year GoC bond yield they are priced on continues to hold steady at about 0.20% below where it was when today’s prevailing fixed rates were set. That should push five-year fixed rates somewhat lower soon.

Meanwhile, five-year variable-rate discounts widened a little last week and are now back to their lowest levels in many years.

Recent warnings about rates rises on the horizon have fallen flat, and at this point, the current momentum points squarely in the other direction.

August 4, 2021

Mortgage |