If you’re in the market for a mortgage today, you may be experiencing some sticker shock now that mortgage rates have risen to their highest levels in about twenty years.

Fixed mortgage rates have moved up into the mid-5% range, and variable mortgage rates are now 6% or more.

Borrowers are wary of inexorably rising variable rates, but they are also understandably reluctant to lock in fixed rates after their recent spike.

With that as the backdrop, here is a comparison of the best current fixed vs. variable options, along with some general advice for anyone now facing that choice.

The first thing to decide is how much sleep you might lose worrying that your mortgage rate might increase. Some people can handle the uncertainty and cost volatility of variable rates more easily than others. If you’re the type who does better with certainty, lock in your rate and be done with it.

Conversely, if you’re willing to live with interest-rate risk, variable rates have the potential to offer a significant saving. When the Bank of Canada (BoC) starts cutting, and they will do so at some point, variable-rate borrowers will benefit immediately while fixed-rate borrowers will have to wait until the end of their locked-in terms.

Variable rates also come with more flexibility.

Borrowers can convert to a fixed-rate term that is equal to or greater than the time remaining on the variable-rate term at any time, and with no fee or penalty. Variable rates also come with penalties that are typically capped at three months’ interest (whereas fixed-rate mortgages come with interest-rate differential penalties that can be much more expensive).

Now let’s compare how today’s variable rates would perform relative to three-year fixed rates under a few different scenarios, all of which have at least some chance of playing out. You can decide for yourself which seems most likely (and I’ll offer my two cents at the end of the post).

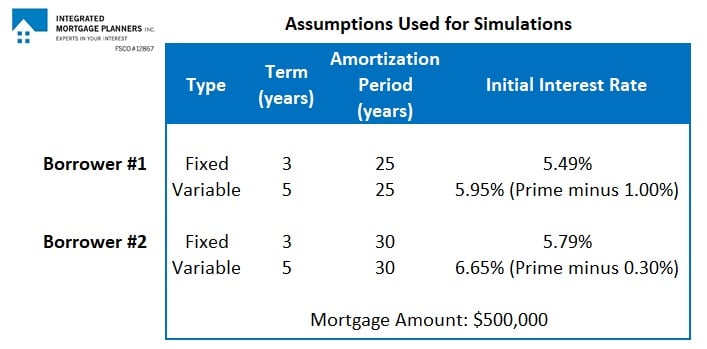

Here are the assumptions that I used to crunch the numbers.

Borrowers

I am going to run simulations using two different hypothetical borrowers:

- Borrower #1 is buying a property with a down payment of less than 20% of the purchase price. That means they will be required to pay for mortgage-default insurance to protect the lender from loss if they default, but once they buy that insurance, they will be eligible for lower default-insured rates. (Note: Insured rates are offered with maximum amortization periods of 25 years and are limited to purchase prices of less than $1 million.)

- Borrower #2 is buying a property for more than $1 million, and as such, they must make a down payment of at least 20% of the purchase price. While they are not eligible for default-insured rates, they also don’t have to pay for mortgage-default insurance, and their amortization can be extended to 30 years.

Mortgage Rates

- Fixed rates: I have decided to use three-year fixed rates in these simulations because I believe that they are the safest middle-of-the-fairway fixed-rate option today, consistent with my recommendations in many recent posts (which you can check out here). I will use an insured rate that is widely available today.

- Variable rates: Variable rates are priced on lender prime rates, which moved in lockstep with the BoC’s policy rate (prime rates are 6.95% today). I am using five-year variable rates because they are much more competitively priced currently and because they are much more available than three-year variable rates. I will use an uninsured rate that is widely available today.

Mortgage Amount

- I am going to assume that both borrowers need a $500,000 mortgage.

Here is a table to summarize:

Simulation #1 – Variable Wins

If you opt for a variable rate now, you will do so on the belief the BoC’s rate hikes will cause inflation, and also demand, to decline fairly quickly.

That is a reasonable assumption.

BoC rate hikes impact our economic momentum with a lag, and the Bank estimates that it can take up to two years before they exert their full bite. The BoC’s first 0.25% policy-rate increase occurred fifteen months ago so we have seen only the tip of the iceberg thus far. We should also note that the impact from the sharpest and most pronounced series of rate hikes that we have seen in modern times will be magnified by our record-high household and government debt levels.

Economic demand has proven resilient thus far, but the factors outlined above could cause it to slow sharply.

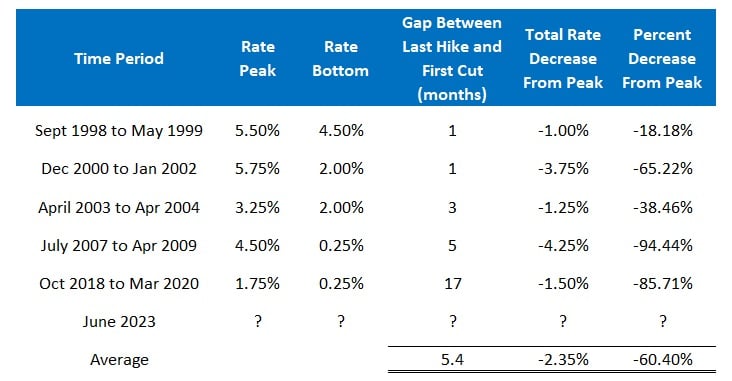

A look at the BoC’s five most recent rate-hike cycles also supports the belief that a series of hikes is typically followed by rate cuts shortly thereafter. If past is prologue, lower variable mortgage rates won’t be that far off (see chart).

In all but one case, the BoC’s first rate cut arrived no more than five months after its last hike. And when rate cuts did materialize, they weren’t mild. in such situations, the BoC dropped its policy rate by an average of about 60% from its cycle high.

Of course, it is not yet clear where the BOC’s policy rate will peak this time. It went up again a few weeks ago, and the bond futures market is currently pricing in one more hike this year.

With all of that in mind, here is how I have assumed that variable rates will evolve in Simulation #1:

- The BoC hikes by 0.25% at its next meeting (July 12), raising its policy rate to 5%.

- It then pauses for six months (which is a little more than the average pause over the Bank’s five most recent tightening cycles). Demand then slows sharply after most consumers deplete the excess savings they built up during the pandemic.

- The BoC starts dropping its policy rate in early 2024, initially with two 0.50% cuts before following with five 0.25% cuts. By December 2024, the Bank’s policy rate has fallen from a peak of 5% to 2.75%. That total rate decrease of 2.25% would be a little below the Bank’s average of 2.35% over its last five cutting stages. The relative decrease of 45% from the previous peak rate would be below the average decrease of 60%.

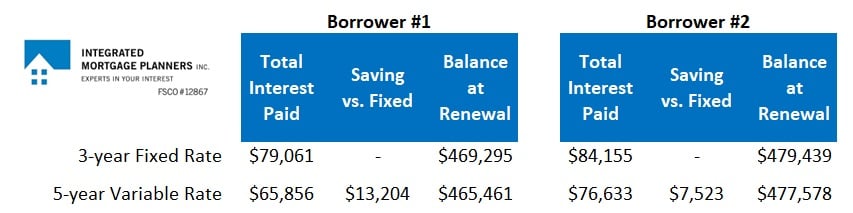

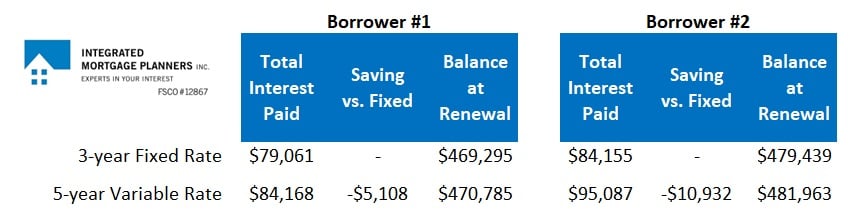

Here is a summary of how fixed and variable mortgage costs would compare:

Simulation #2 – Fixed Wins

While there is no debate about whether the BoC’s rate hikes will slow our economy and reduce demand, there is much more debate about whether rate hikes will sufficiently cool inflation.

In the early days of the current inflation run up, most of the pressure was emanating from external forces – supply chain issues tied to pandemic shutdowns and commodity price spikes that were linked to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. That type of inflation was beyond the reach of BoC rate hikes.

Those pressures have now largely abated or worked their way through the inflation data.

Today’s inflation is being primarily driven by domestic factors tied to elevated levels of government and consumer spending, which should be sensitive to BoC rate hikes. But thus far demand hasn’t cooled as much as expected, and higher inflation is becoming more entrenched as rising labour costs persist and productivity levels continue to fall.

If the BoC is determined to wait until our Consumer Price Index (CPI) returns to its 2% target before cutting rates, we’ve still got a long way to go.

Our annualized headline CPI increased from 4.3% in March to 4.4% in April, and other shorter-term measures of inflation are now re-accelerating. At the same time, the tailwind from base effects will also abate over the summer. (As a reminder, the tailwind from base effects occurs when higher prices from last year roll out of the CPI data set.) That means that inflation reductions will be harder to come by from now on.

Here is the path that I have assumed for variable rates if inflation forces the BoC into a higher-for-longer approach:

- The BoC hikes by 0.25% at its next meeting (July 12), and once more before the year is out.

- It then takes twelve months to inflict the economic pain necessary to materially slow demand. But even then, inflation doesn’t get all the way back to 2%.

- The Bank eventually cuts rates to provide some relief to borrowers, perhaps justifying the move by relying on the fact that while its mandate is to keep CPI at a target rate of 2%, that mandate includes a more flexible CPI target band, which allows fluctuations between 1% and 3%.

- The first 0.25% rate cut arrives in December 2024 and the Bank cuts by the same amount five more times for a total reduction of 1.50%. By October 2025, its policy rate has fallen to 3.75%.

Here is a summary of how fixed and variable mortgage rate costs would compare for our same two borrowers:

Simulation #3 – We Muddle Through

While bond market forecasts have tended to swing from one extreme to another, in reality, competing forces can cancel each other out, and that often moderates the pace at which rates fluctuate.

That might mean, for example, that the lagged impact of the BoC’s rate hikes causes demand to slow sharply, but other factors such as geopolitics or climate events cause shortages and concomitant price spikes. In such scenarios, inflation wouldn’t decline on a consistent downward path. That would compel the BoC to both pause from making additional hikes and to delay the onset of cuts.

Here is an example of how variable rates might evolve in that type of scenario:

- The BoC hikes by 0.25% at its next meeting (July 12) and then moves back to the sidelines.

- Inflation decelerates for a few months but then briefly ticks up again. The Bank holds its policy rate steady at 5.00% even as our economy stalls because it must keep inflation expectations anchored.

- The BoC finally starts to drop its policy rate, by 0.25%, in October 2024.

- It then walks its policy rate down to 2.75% in a series of 0.25% cuts designed to keep a lid on inflation while also trying to stimulate productive investment.

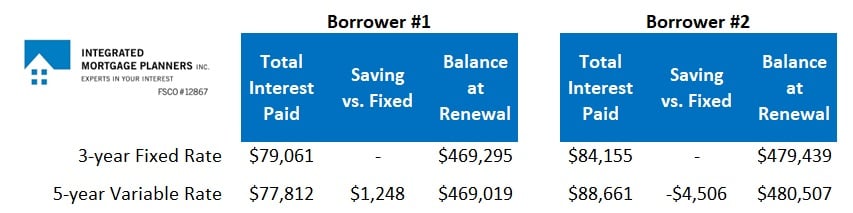

Here is a summary of how fixed and variable mortgage rate costs would compare under this simulation:

The first thing that jumps out in the simulations above is that the insured borrower has more to gain and less to lose on a relative basis than the uninsured borrower. That makes sense because the gap between insured fixed and variable rates is wider.

Each reader will have to decide for themselves which simulation seems to best fit their expectations. For my part, I think the BoC will still prefer to err on the side of overtightening, all else being equal, and I still subscribe to the higher-for-relatively-longer view.

Because of that, I continue to believe that the safest pick for anyone who is currently in the market for a mortgage, and who wants to aim for the middle of the fairway, is a three-year fixed rate.

Anyone making that choice today must accept the risk that they will be paying an above-market rate in the latter part of their term. But that is a trade-off most borrowers will make when the alternatives are even longer terms (which exacerbate that risk) or variable rates and shorter-term fixed rates (which seem to be rising inexorably).

At times like this, we could all use a good night’s sleep, even if we end up having to pay extra to get it.

.jpg?width=883&height=328&name=Rate%20Table%20(June%2026%2c%202023).jpg)

The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields bounced around last week and finished about where they started. But that didn’t stop lenders from continuing to raise their fixed rates to new post-pandemic highs.

Five-year variable-rate discounts held steady last week. The bond futures market is pricing in another BoC rate hike in the near-term, but that could change after Statistics Canada releases its latest inflation data tomorrow and its latest GDP numbers on Friday. Stay tuned.

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

June 26, 2023

Mortgage |