Last week the US Federal Reserve joined the Bank of Canada (BoC) when it shifted to the talk-tough-and-do-nothing phase of its monetary-policy cycle.

The Fed raised its policy rate by another 0.25%, as was widely expected, but its latest policy statement contained a subtle shift in wording, which signalled that it will likely pause additional hikes for the time being.

Instead of repeating its previous assessment that “some additional policy firming may be appropriate”, the Fed said that it will monitor the incoming data and will be “prepared to adjust the stance of monetary policy as appropriate if risks emerge”.

In addition to cooling still-hot inflation, the Fed must account for the US banking crisis, which is reducing liquidity in the US financial system and creating impacts like those caused by additional rate hikes and the current game of chicken being played by the Republicans and Democrats in the US Congress over raising the US Federal government’s debt ceiling. (The US federal government will eventually default on its debt obligations if no agreement is reached.)

The Fed’s softened stance gives it time to let the banking crisis and debt-ceiling fight play out and to observe the still unfolding impacts of the hikes that it has already made, which can take up to two years to fully materialize.

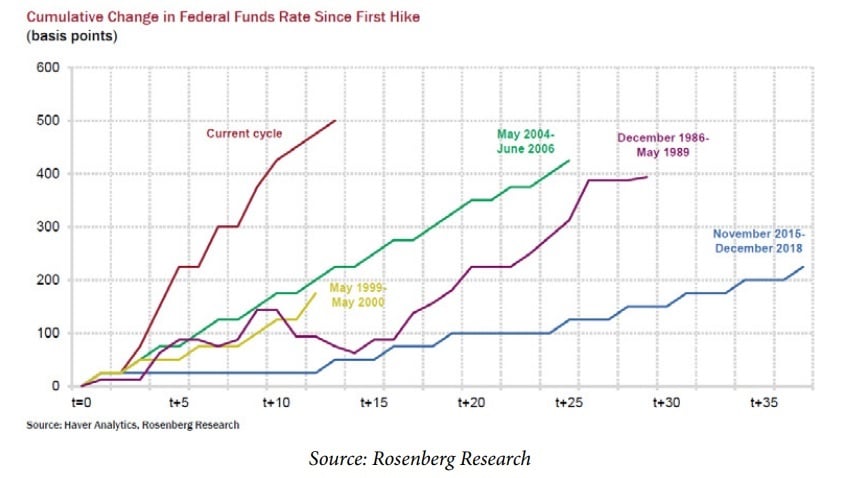

That latter point is key because while the US and Canadian economic data have held up surprisingly well thus far, the full bite from the rate hikes already on the books is not yet evident. As economist David Rosenberg notes, the Fed’s current rate-hike cycle has been steeper than any we have experienced in modern times (see chart below), and that increases the likelihood that the still unrealized impacts will be significant.

Rosenberg also calculates that it has taken an average of 10 months after the US bond-yield curve inverts before a US recession ensues, and he noted that the US bond yield curve inverted 10 months ago. If past is prologue, it won’t be much longer before signs of broader economic slowing become more evident on both sides of the 49th parallel.

That puts us at an interesting point in the mortgage-rate cycle.

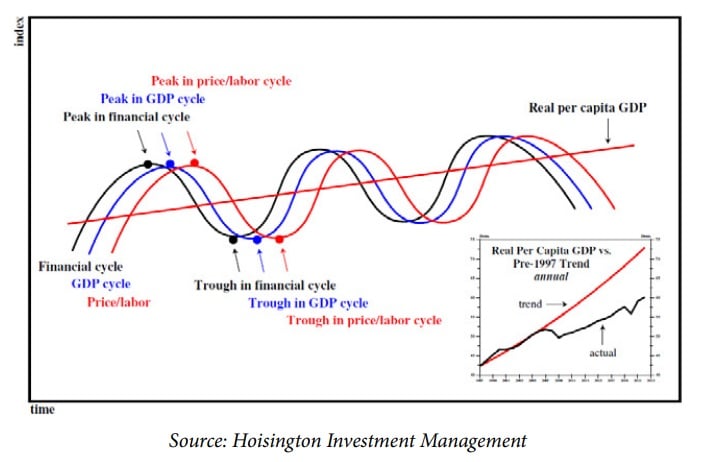

We all expect that rate hikes will reduce economic activity. There is increasing evidence that this is now happening, but not all our economic sectors will slow at the same time. Lacy Hunt, Chief Economist at US investment firm Hoisington Investment Management, offered the chart below to explain how the business cycle oscillates in three distinct waves (see chart).

If we overlay our current data on the chart above, everything lines up.

The first turn in the financial cycle was via rate hikes (the BoC hiked by 4.25%). Then our GDP slowed (Stats Can’s latest forecasts project an outright GDP decline in March). Now price and labour-cost momentum are starting to show signs of slowing (this will be the last shoe to drop, which is why our employment data are classified as lagging indicators.)

Hunt notes that this pattern has been evident to economists all the way back to 1752. (Both the Rosenberg and Hunt charts cited above came from John Mauldin’s most recent weekly newsletter, which I highly recommend.)

Our central bankers are aware of these patterns, but the general public is not. That’s important because when it comes to inflation, perception matters. If the public looks at today’s lagging indicators and believes that they will keep inflation higher for longer, that belief can become self-fulfilling prophecy. Simply put, expectations of higher inflation can cause more of the real stuff to materialize if it accelerates purchase plans and thereby raises near-term demand.

Last week’s employment data provide a good example.

Statistics Canada confirmed that our economy added 41,000 new jobs in April. That result was double the consensus forecast and continues an impressive record of job creation that began in January when we started the year by adding 150,000 new jobs in what is historically a slow month for job growth.

Our central bankers see strength in a lagging indicator at a time when our more important leading indicators are slowing. But the public sees mainstream media reports of “another blockbuster Canadian jobs number” that “smashed expectations”., That narrative feeds into dangerous inflation expectations.

Central bankers don’t want to raise rates because the leading indicators tell them not to, but they keep talking tough, because inflation expectations, even if based on lagging indicators, must also be managed.

Last month’s average wage growth of 5.2% year-over-year confirms that labour costs remain sticky, and I continue to believe that inflation will take longer to fall back to 2% than the bond market is currently pricing in. The most important question for mortgage borrowers deciding between fixed and variable rates is when they think this will happen.

If you take a variable-rate mortgage today, you will pay a premium of about 1% over the available fixed-rate equivalent, which only makes sense if you believe that the BoC is going to start cutting rates significantly and soon.

That might end up happening. But I think it is an aggressive bet because the Bank doesn’t expect inflation to return to its 2% target (its stated prerequisite for rate cuts) until the end of 2024 and because inflation has consistently proven stickier than expected.

On the other hand, today’s three, four, and five-year fixed rates are tied to bond yields that are already pricing in the expectation that inflation will fall faster than our central bankers are forecasting. Once you lock in one of those rates, you will be insulated from whatever happens next (and the only way you will end up overpaying is if inflation falls even faster than the bond market currently expects).

Based on those factors, I think three-year fixed-rate options strike the ideal balance. They are offered at rates that are among the lowest currently available and should be renewing at a time when it seems reasonable to expect that inflation will have been brought to heel, even if we get a few hiccups along the way.

The Bottom Line: Government of Canada bond yields bounced around last week, but at the close of business on Friday, they had finished about where they started.

Fixed mortgage rates have held steady of late, but that could change this Wednesday when we receive the latest US inflation data, for April. An upside surprise could easily move rates higher.

Variable-rate discounts were unchanged last week, and I continue to believe that rate cuts won’t materialize until the second half of 2024.

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

May 8, 2023

Mortgage |

.jpg?width=883&height=328&name=Rate%20Table%20(May%208%2c%202023).jpg)