Inflation spiked last month.

Statistics Canada confirmed that our Consumer Price Index (CPI) rose by 0.7% on a year-over-year basis in October. The increase was led by food prices and costs associated with housing construction, which rose at their fastest pace in fourteen years.

While last month’s result came in far above the consensus forecast of 0.4%, our overall CPI remains well below the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) target of 2%.

Two of the Bank’s three key sub-measures of core inflation also increased by 0.1% last month, with CPI-common rising to 1.6% and CPI-trim rising to 1.8%. CPI-median held steady at 1.9%.

In its latest Monetary Policy Report (MPR), the BoC had forecast inflation of only 0.2% for the third quarter of 2020, and as such, our latest inflation data have fueled speculation that the BoC may be forced to either raise its policy rate and/or curtail its quantitative easing programs sooner than expected.

Here are five reasons why I disagree with that view:

- The BoC won’t front-run the U.S. Federal Reserve.

Bluntly put, there is no way the BoC will raise its policy rate before the Fed. That would cause the Loonie to rise against the Greenback and heap further suffering on our export sector.

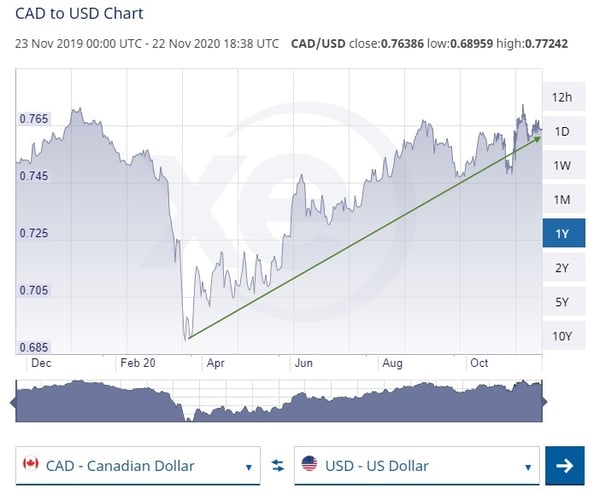

The Bank is already concerned about the Loonie’s value, which has soared since the pandemic began (see chart below).

The Fed’s most recent dot plot chart, which summarizes each individual Fed official’s forecast for its policy rate, doesn’t have it moving higher until the end of 2023 (and the Fed’s rate-hike forecasts are known for being early, not late).

On a related note, in August the Fed announced a major policy shift to “average inflation targeting.” This policy means that the Fed will allow a period of above-target inflation to follow a period of below-target inflation, like the one the U.S. economy is experiencing now. It also likely means that the longer inflation stays below 2% now, the longer the Fed will allow it to stay above that level later.

If the Fed is going to delay rate hikes and let the U.S. economy run hot for an extended period after U.S. inflation reaches or exceeds 2%, then the BoC will have to do the same.

- The BoC has emphasized that it won’t start raising its policy rate until our domestic recovery is well underway.

The recent uptick in inflation, surprisingly robust though it was, still only took our overall CPI rate to 0.7% on a year-over-year basis.

If the Bank reacted to that uptick in any way, it would be in anticipation of rising inflationary pressures ahead. But in all of its recent guidance, the BoC has made it clear that this time around it will adjust in reaction to, and not in anticipation of, higher inflation.

That guidance also gives the Bank all of the cover it needs, for now, to shadow the Fed without having to overtly match its average inflation-targeting policy.

- The inflation spike isn’t likely to compel the BoC to curtail its quantitative easing (QE) programs either.

There has been recent speculation that the BoC pulled back on its QE programs in response to rising inflationary pressures, but from my desk, that doesn’t appear to have been the case.

For starters, the Bank’s decision to reduce its weekly purchases of government bonds from $5 billion to $4 billion had nothing to do with rising inflation.

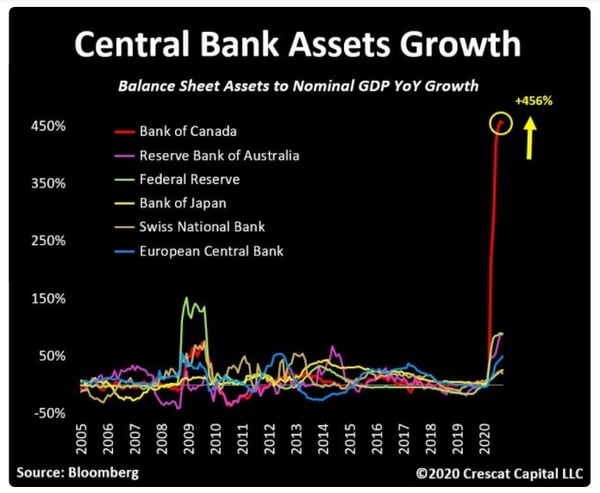

Its QE purchases have been so aggressive that the Bank is dominating the entire market. Consider that the BoC now owns 35% of our total sovereign debt outstanding and will own 50% of it by the end of this year.

If the Bank hadn’t slowed its pace of purchases, it wouldn’t have been long before there weren’t enough government bonds left to trade in the open market.

Ironically, when the BoC started QE, it cited the need to preserve market liquidity. But over the ensuing months, the Bank has bought so much government paper that institutional investors started to express concern that its massive purchase volumes were cornering the market and restricting liquidity instead of enhancing it.

The chart below puts the scale of the BoC’s current QE programs in perspective. It compares the Bank’s balance-sheet growth relative to our GDP to a selection of other central banks and their economies.

The BoC is cutting back its asset purchases from $5 billion a week to $4 billion a week because it wasn’t leaving enough bonds for the rest of the market. That adjustment has everything to do with market dynamics and nothing to do with inflation.

(On a related note, the Bank has also shifted its focus from shorter-term bonds to longer-term bonds that will, in part, more directly impact household borrowing rates. In this post I explain why that should put downward pressure on our five-year fixed mortgage rates going forward.)

- Our current output gap greatly reduces the odds that rising inflationary pressures will last.

The BoC watches our output gap closely because it provides a reliable gauge of whether rising inflationary pressures are likely to be sustained. (As a reminder, the output gap refers to the gap between our economy’s actual output and its maximum potential output.)

Our output gap had stopped narrowing even before COVID hit, and it won’t come as a surprise to anyone that it has widened considerably since then.

In its latest MPR, the Bank noted “significant slack” in our economy and forecast that our output gap wouldn’t close until sometime in 2023. The BoC is now focusing its QE purchases on the bonds that are tied to borrowing rates that most directly impact households and businesses to specifically help address that gap. A short-term surge in inflation won’t alter that approach.

On a related note, the current state of our labour market goes a long way to explaining why our output gap is now so wide. While we have recovered the majority of jobs that were originally lost to the pandemic, last month Stats Can estimated that more than 600,000 still haven’t been recovered, and that total remains well above our previous record of 425,000 jobs lost during any prior recession.

Now that the second wave has brought back increased restrictions and in some cases, lockdowns, our employment recovery may well stall out (which is a topic I explored in this recent post).

If that happens, the output gap will widen further and any uptick in inflation will matter even less.

- It may take MUCH longer for meaningful inflation to materialize.

The consensus narrative is that, at some point, inflation is going to take off like a rocket – most probably when all of the excess money being printed by central banks starts circulating throughout the global economy. At that point, watch out.

The problem with that view is that there is little evidence to support it.

To the surprise of many market watchers, countries that have engaged in aggressive QE have consistently seen their inflation rates fall.

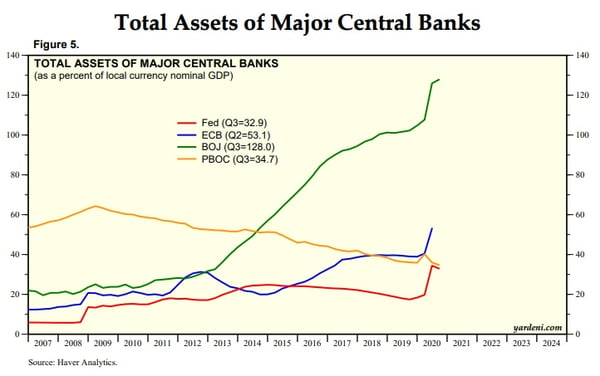

The BoC is relatively new to the QE game. It didn’t use it in response to the Great Recession of 2008 and only turned to it now in response to the pandemic. But other central banks have been using QE for much longer, and the granddaddy of them all is the Bank of Japan (BoJ).

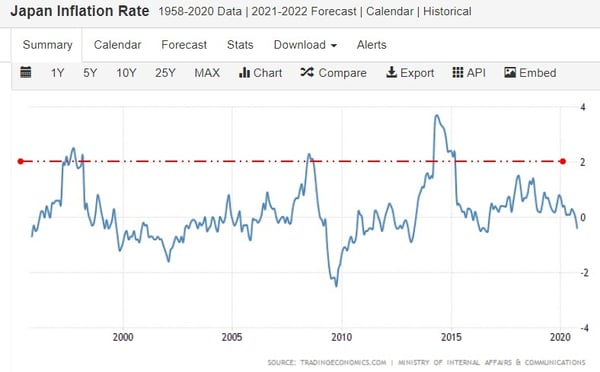

The BoJ has been using QE since the last 90s, and if any economy should have seen higher inflation as a result of rampant money printing, Japan is the one (see chart below).

So how has that worked out for them?

I’m going to turn the answer to that question over to economist David Rosenberg:

“We had core CPI data out of Japan and the YoY trend went further into deflation to -0.7% in October from -0.3% in September. This is the sharpest move into deflation terrain since March 2011. A country with a 700% total debt-to-GDP ratio, two decades of zero interest rates, and a central bank balance sheet that is 130% of GDP. Nice to see how all the credit creation has managed to spur on a reflationary backdrop. Shades of what’s to come in the US.”

Here is a chart that shows Japan’s inflation rate over the entire period that it has experimented with eye-watering levels of QE.

Why is anyone confident that we should expect a different outcome in Canada?

-1.jpg?width=600&name=Rate%20Table%20(November%2016,%202020)-1.jpg)

The Bottom Line: Canadian inflation spiked last month, but for the reasons outlined above, I don’t think that will compel the BoC to alter its QE programs or, heaven forbid, raise its policy rate. That makes it highly likely that variable mortgage rates won’t move higher for quite some time to come.

Five-year fixed mortgage rates didn’t rise last week as many warned they would. The five-year GoC bond yield these rates are priced on dropped a little instead, and as such, the threat of an imminent increase in five-year fixed rates appears to have now abated.

Image credit: iStock/Getty Images

David Larock is an independent full-time mortgage broker and industry insider who works with Canadian borrowers from coast to coast. David's posts appear on Mondays on this blog, Move Smartly, and on his blog, Integrated Mortgage Planners/blog.

November 25, 2020

Mortgage |