Once again, is the real problem supply or demand?

As featured in Move Smartly's Monthly Market Report for Sept 2020 - Read full report here

As house prices continue to rise amidst the Covid-19 generated economic slowdown feeding concerns about market unsustainability, Canada’s housing authorities appear to be at odds.

As house prices continue to rise amidst the Covid-19 generated economic slowdown feeding concerns about market unsustainability, Canada’s housing authorities appear to be at odds.

Early this summer, as Bank of Canada’s (BoC) Governor Tiff Macklem reassured mortgage borrowers that interest rates would remain low for some time to come, the head of the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), Evan Siddall, doubled down in his fight against “the glorification of homeownership.”

Siddall’s arguments were recently highlighted in a supportive Globe and Mail editorial which also reached the rather familiar conclusion that the “true problem” with Canadian real estate is that we “have a shortage of housing.”

The problem with this conclusion is that it is a too-easy-to-argue solution to a more difficult, two-sided problem.

Recent economic literature has noted that all “superstar cities” display a similar problem: in addition to supply side constraints, such cities generate demand amongst higher income households which crowd out lower income households. It does not take an expert to know that Toronto’s housing market is supply constrained – but without a discussion of the demand side, this discussion is incomplete.

Demand is harder to talk about for several reasons. Compared to changes in supply, which are preceded by building permit applications and other measurable factors, demand changes are often harder to forecast or even foresee.

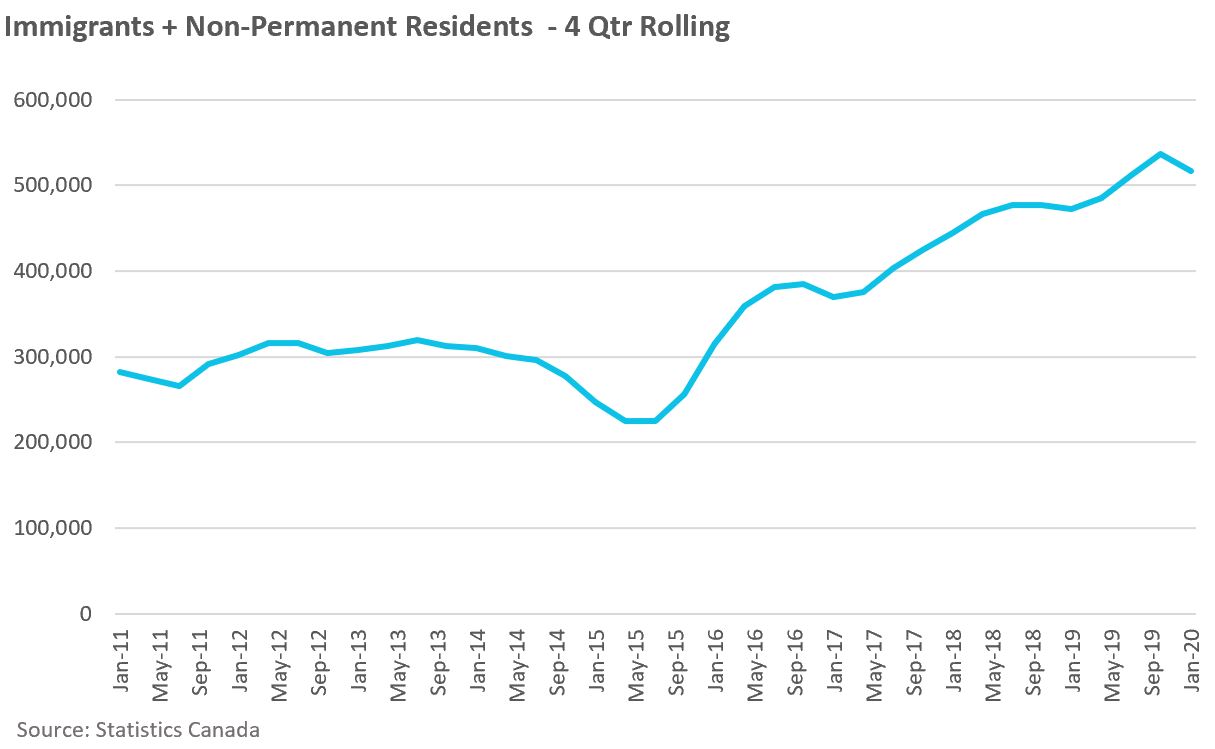

At times, demand may be a result of other policy goals. Immigration, including that of non-permanent residents and foreign students, which is vital to Canada’s economy, also has an impact on its real estate. When Canada experiences a change in levels like the surge in immigration we’ve seen over the past four years (see chart below), much of which tends to funnel to the Toronto area, it is not clear that any superstar city can build fast enough to respond to such a demand shock to prevent upward pressure on house prices.

The boom in house sales and prices we are now seeing is being driven by the spillover of pre Covid-19 immigration levels and cheap money. Add to this an exogenous shock, Covid-19, which has generated a shift to working and schooling from home, and the result is a surge in demand for houses in the GTA’s outer suburbs and cottage country. Before Covid-19, there was no significant supply shortage in Clarington, Innisfil and Essa – these areas were not the hottest markets in the GTA with houses getting 20+ offers on offer nights and prices rising 20+% year over year as we are seeing now.

Incidentally, while the Globe editorial notes that Siddall believes in building housing density on a “grand scale,” a similar swing in demand may make such a project less urgent at present. This month average condominium rents in Toronto are down 13% and falling and resale condo listings are surging as Covid-19 has emptied denser urban areas of their service workers and students, where 100,000 condo units still in the construction pipeline are due to add to increasing supply.

More importantly, politicians and policy makers interested in “grand building” are often less full-throated about how money for such projects may be found – consider the role that property investors play.

Indeed, the CMHC itself believes that policies that promote the interests of Investors and the financialization of housing are necessary.

A report published in 2018 states that:

“these investors may have played a critical role in increasing the supply of new housing in Canada. Although further analysis is needed, we therefore caution that actions curtailing investors’ interest in financing new housing construction could impact long-term housing supply adversely”

Examining Escalating House Prices In Large Canadian Metropolitan Centres, CMHC, 2018

But CMHC’s conclusions are problematic. The reason investors have been responsible for much of the new condominium construction In the GTA over the past decade is not because end-users don’t want to buy a new home but because optimistic investors are the marginal buyers in the market who will pay the highest price. It’s why pre-construction condominiums in the Toronto area sell for 20-30% more than existing resale condos, pricing end-users out of the market.

Evidence from British Columbia’s speculation and vacancy tax suggests that vacant homes and foreign capital are all making it harder for BC residents to buy a home.

In their 2017 Financial System Review, the Bank of Canada argued that the (eventually unsustainable) acceleration in GTA home prices in 2016/2017 that pushed prices up 30% year-over-year was likely driven by investor speculation.

All of this is not to suggest that there is no case for well-considered supply side policies – but more often than not there are insidious problems on the demand side that could be addressed that may offer more immediate results when compared to supply side policies which could take decades before they have any impact on the market.

Follow John's latest updates on Twitter, YouTube, Facebook or Instagram

John Pasalis is President of Realosophy Realty, a Toronto real estate brokerage which uses data analysis to advise residential real estate buyers, sellers and investors.

A specialist in real estate data analysis, John’s research focuses on unlocking micro trends in the Greater Toronto Area real estate market. His research has been utilized by the Bank of Canada, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).