Author John Pasalis is the President of Realosophy Realty, a Toronto real estate brokerage which uses data analysis to advise residential real estate buyers, sellers and investors. He is a top contributor at Move Smartly, a frequent commentator in the media and researcher cited by the Bank of Canada and others.

Average house prices jump up after months of holding steady as new listings remain historically low as average condo prices rise slightly.

FREE PUBLIC WEBINAR: WATCH REPORT HIGHLIGHTS

Join John Pasalis, report author, market analyst and President of Realosophy Realty, in a free monthly webinar as he discusses key highlights from this report, with added timely observations about new emerging issues, and answers your questions. A must see for well-informed Toronto area real estate consumers.

The Market Now

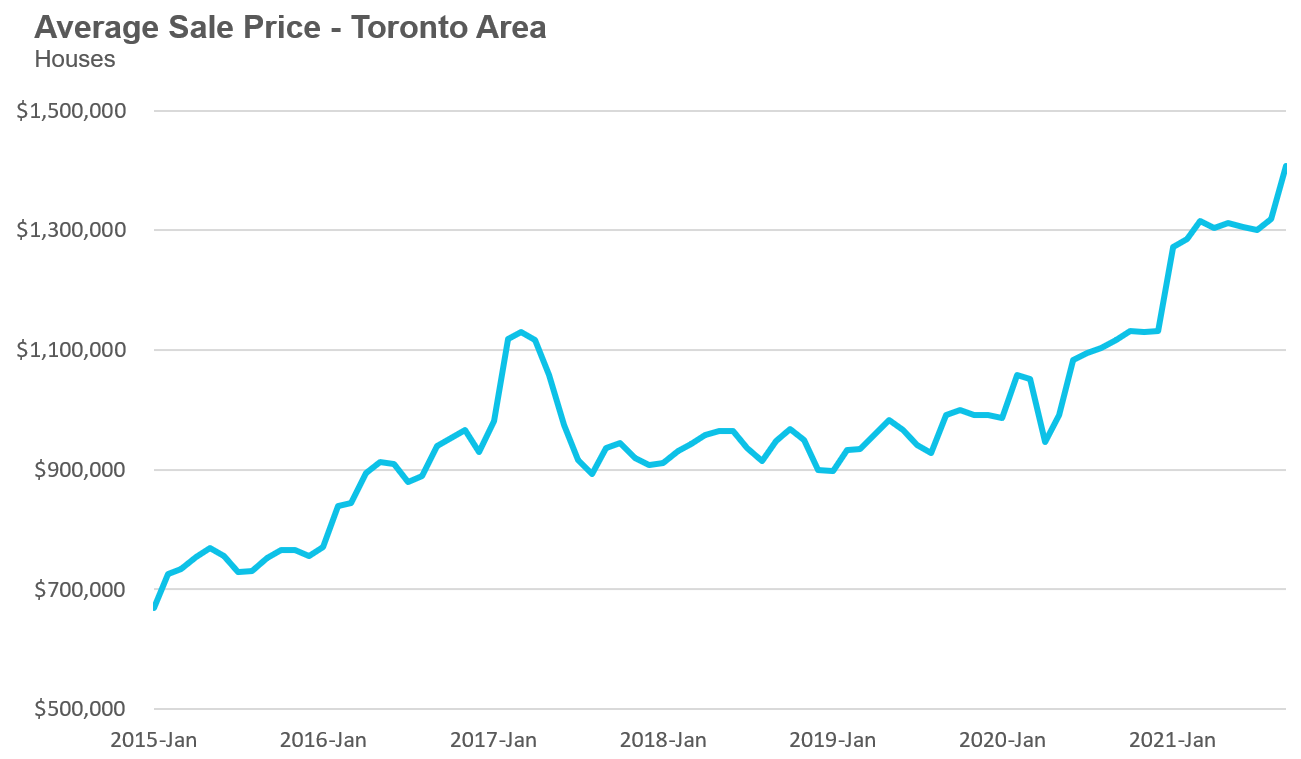

The most recent Toronto area real estate market statistics (for last month, September 2021) have revealed an end to the average price plateau of $1.3M for (low-rise) house prices, which we’ve been seeing for most of this year, with prices now climbing to $1,407,190. This represents an increase of 7% over the previous month and 26% year-over-year.

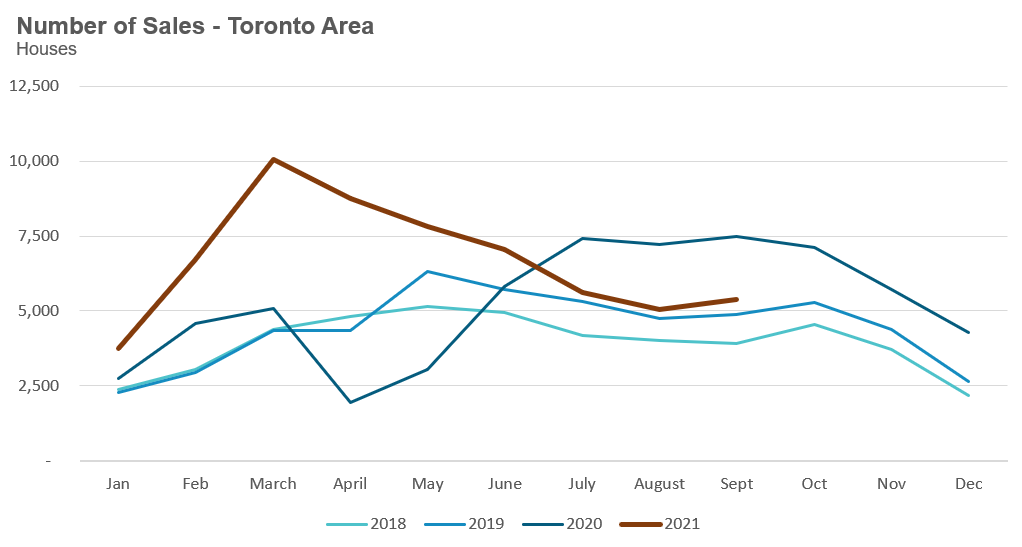

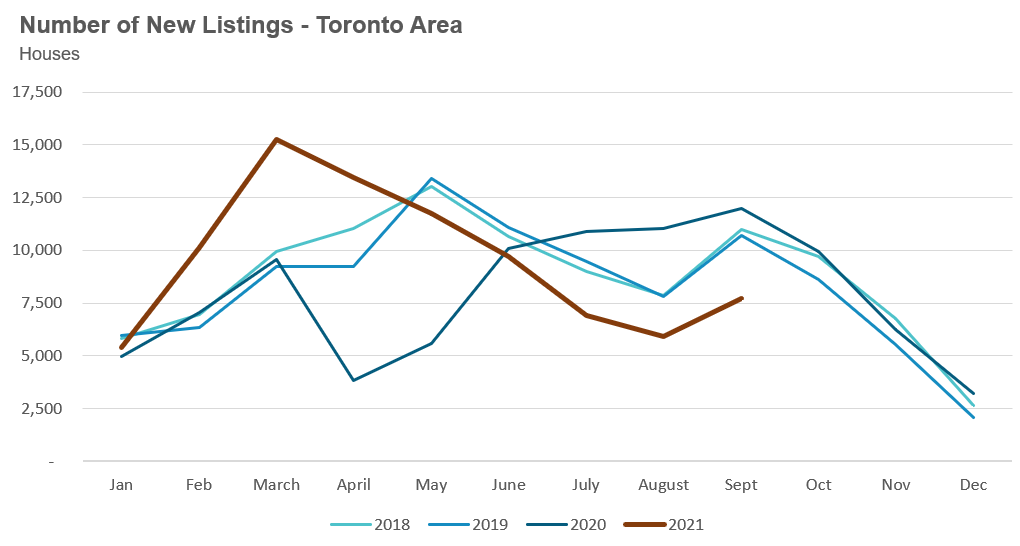

While house sales were down 28% on a year-over-year basis, sales were well above pre-COVID levels for September sales in 2018 and 2019. Conversely, new listings in September picked up over the previous month’s levels, but were down 36% over last year and well below levels in 2018 and 2019.

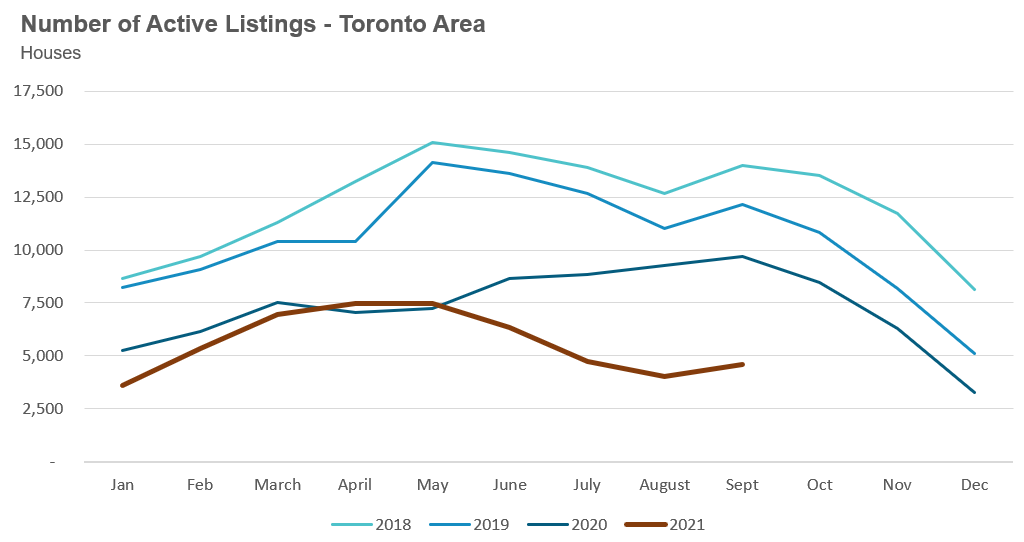

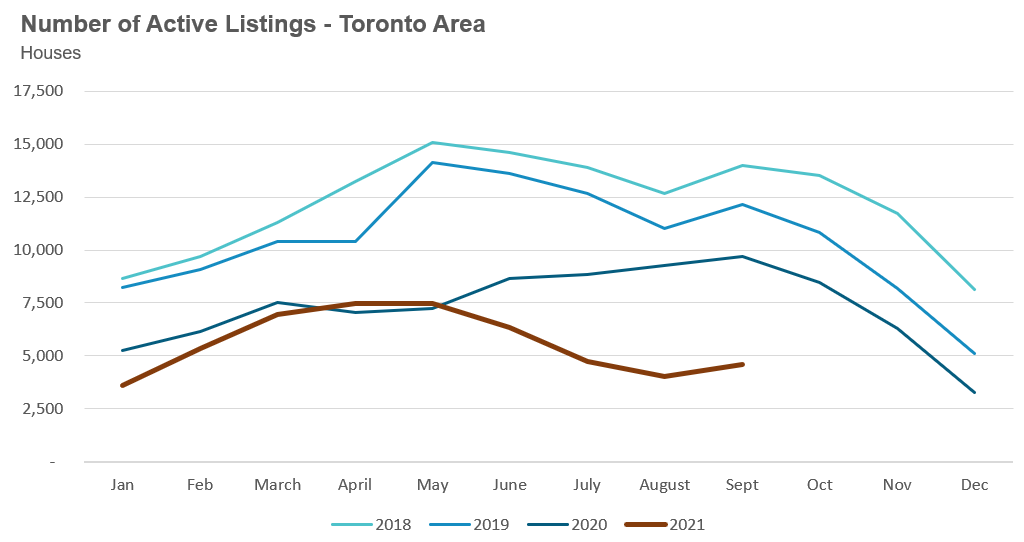

At the end of September, the Toronto area had only 4,607 houses available for sale, a 53% decline from inventory levels last year and well below the roughly 11,000 active house listings that are more typical for the month of September.

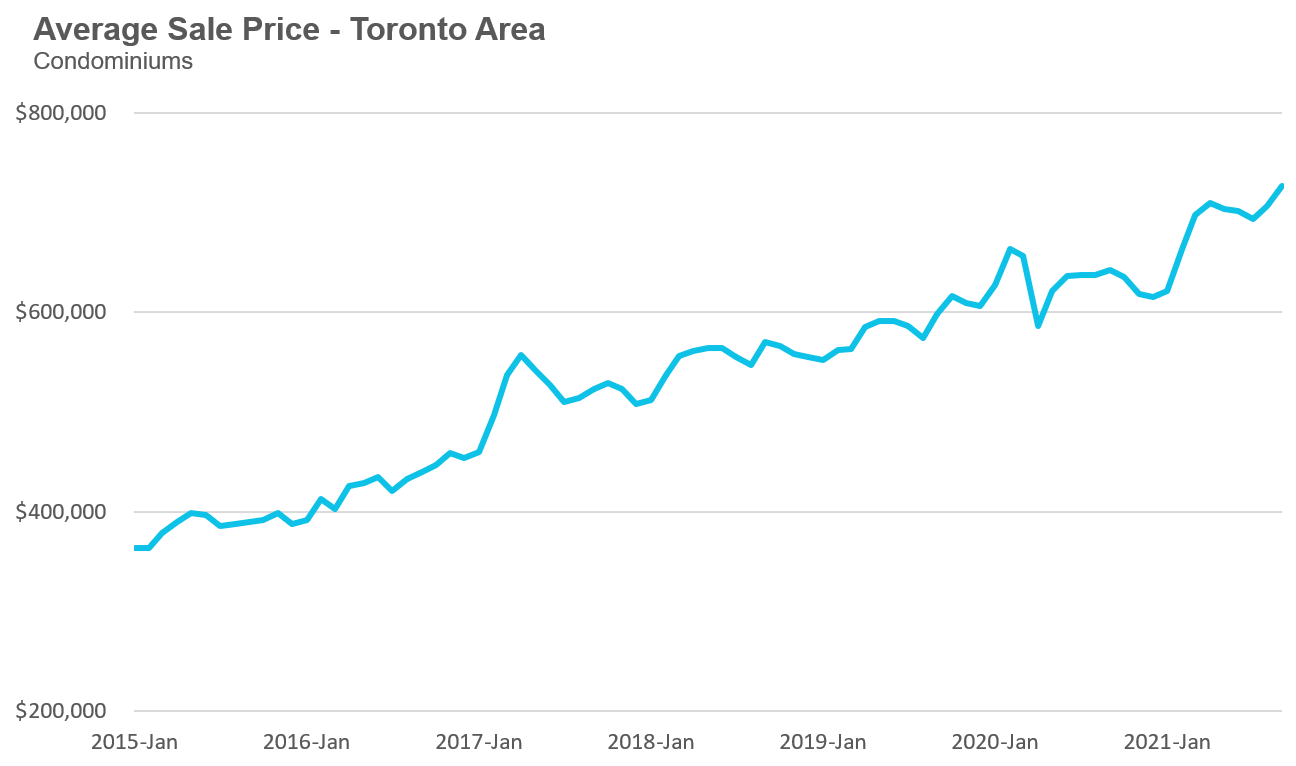

The average Condominium (condo) price in September was $726,809 while the median was $657,500, both up 13% over last year. This marks a more modest increase from the $700K average price plateau we’ve been seeing for most of this year.

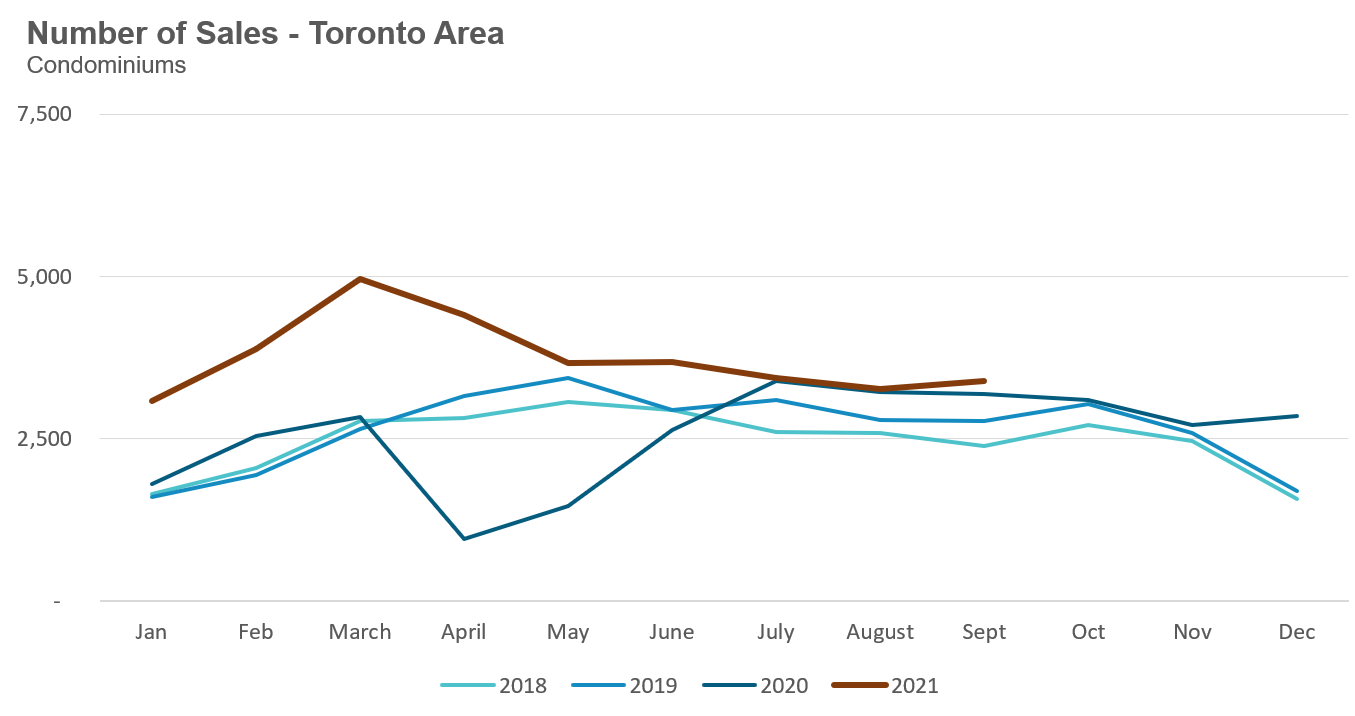

Condominium (condo) sales in September were up 6% over last year and above the pre-COVID levels for the same month in 2018 and 2019.

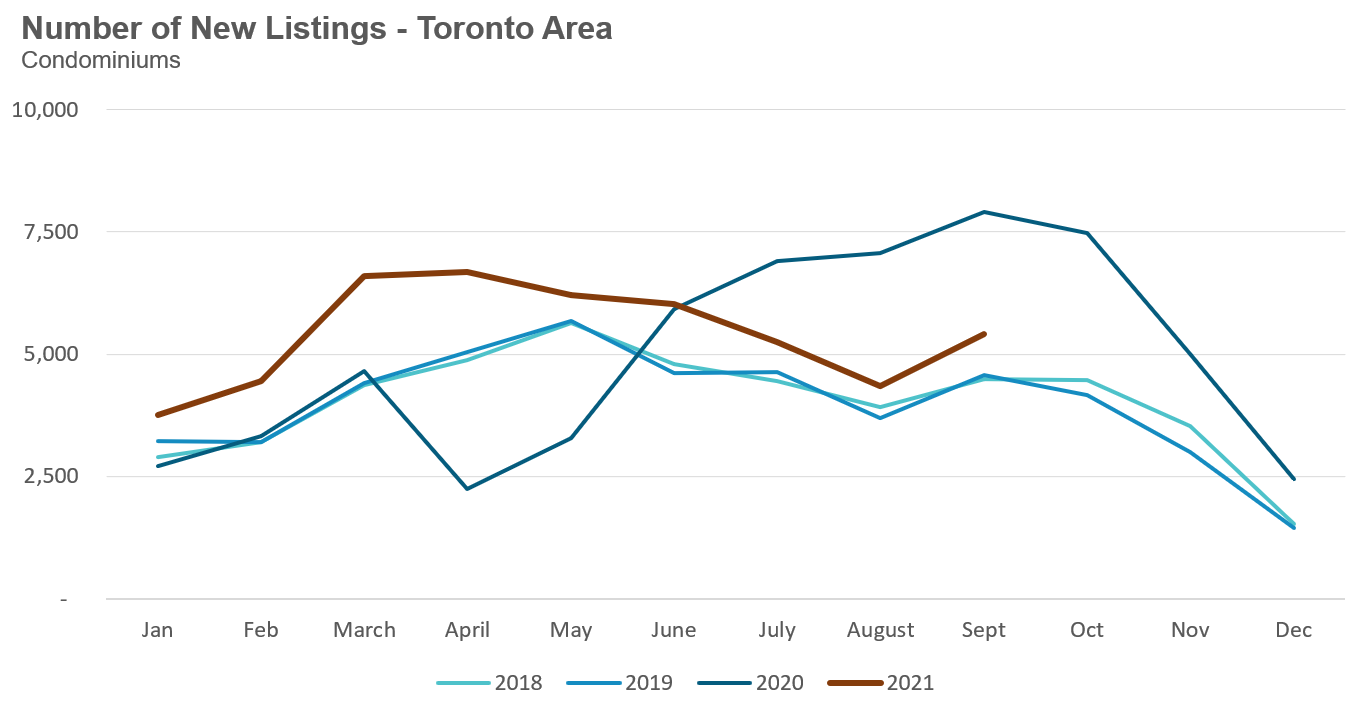

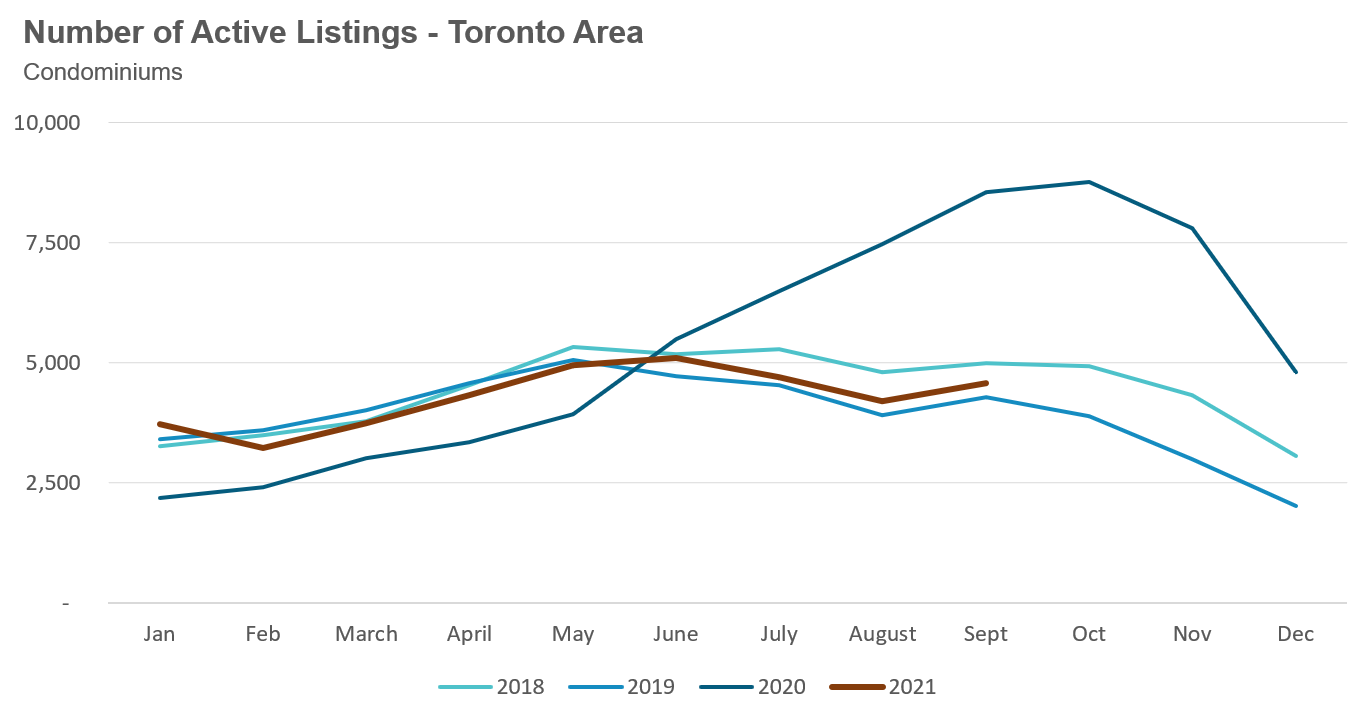

New condo listings were down by 32% in September 2021 over last year, but well above the volumes in 2018 and 2019. The number of condos available for sale at the end of the month, or active listings, was down 47% over last year.

(For all monthly statistics for the City of Toronto and the GTA, see the final section of this report.)

How seriously should we take the latest alarm from Canada's top housing authority?

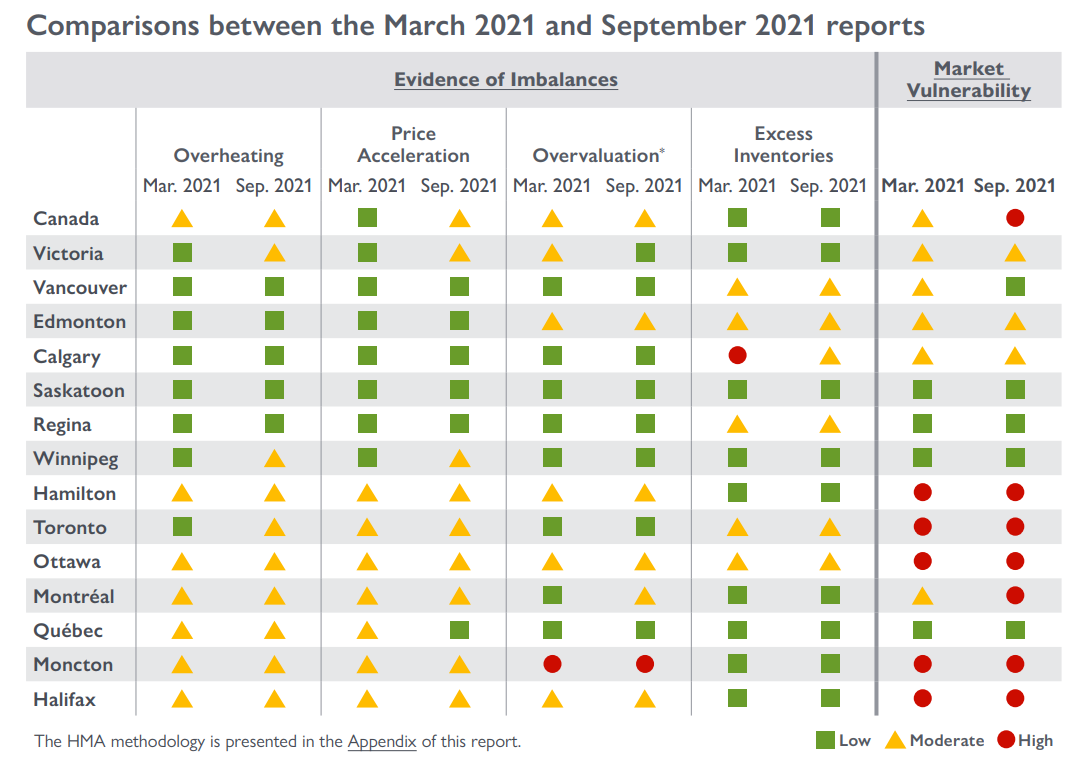

The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) released their latest Housing Market Assessment last month and their assessment for the market vulnerability for Canada’s housing market was raised from moderate to high risk.

Highlighting risks in Canada’s housing market is an important job, but given CMHC’s recent track record I do worry that their words of caution will fall on deaf ears.

For those who may not recall, CMHC released a very pessimistic forecast at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic predicting that prices would fall 9%-19%.

But the problem wasn’t so much with their forecast, which was reasonable given the uncertainty at the start of the pandemic, but rather their overconfidence that their forecast would be correct. Their CEO at the time went as far as saying that people should “question the motivation of anyone who wants you to believe prices will go up” during the pandemic.

But prices did go up, surging up as much as 30% in much of the country.

CMHC’s concern that Canada’s housing market is at high risk is arguably far more important and relevant today given the strong rate of appreciation we have seen over the past year. This does not mean I think house prices are going to fall anytime soon, but it would be foolish to not be concerned.

Any student of history knows that rapid rises in house prices and debt are a cause for concern, not celebration. University of Chicago economist and co-author of the book House of Debt Amir Sufi reminded us of these risks recently:

“A robust finding in the macrofinance literature is that a large rise in property prices and the associated debt predicts (1) a decline in economic activity, (2) a rise in probability of financial crisis, and (3) a crash in bank equity prices ... After we wrote House of Debt, people used to say, "what about china"? i used to say, "i don't know much about china, but i know that historical episodes of strong house price and debt growth are usually followed by bad things"

— Amir Sufi, Twitter

Most people I speak with seem to believe that these types of historical trends don’t apply to Canada, and especially not Toronto. We’re a special market where house prices only move in one direction, straight up. Immune to any of the fluctuations one may come to expect from a normal housing cycle because in Canada, the underlying cause of high house prices is a “lack of supply”, and for that reason — prices can never go down.

I personally don’t subscribe to that belief — I do believe in historical trends, but the challenge with these trends is that one never knows when the down cycle might start, what might trigger it and how severe it’s going to be.

I personally think the risk of a downward trend in Canadian house prices in the short-term is very low. Inventory levels are still far too low and even if the market shows early signs of cooling, I’m confident policy makers have enough levers to stimulate the housing market further — at least over the short term. What will the market look like 2-3 years from now is anyone’s guess, but I feel it’s always more prudent to be on the lookout for early warning signs in the market rather than assuming prices will keep rising by double digits forever.

Why is zoning being seen as part of the solution to the problem of housing unaffordability?

The Ontario Real Estate Association (OREA) is urging the provincial government to end exclusionary single-family zoning rules in high-demand areas.

Exclusionary single-family zoning rules prevent someone from buying a bungalow and tearing it down to build two semi-detached homes, or three row houses or even a detached duplex or triplex. If you tear down that bungalow, the only thing you can build is another single-family detached house.

“In too many Ontario cities, it defies common sense that you can take a bungalow and turn it into a monster four-storey home for one wealthy family, but you cannot build affordable townhomes for multiple families without red tape, runaround, and exorbitant costs”

“You cannot grow south into Lake Ontario or north into the Greenbelt, so we need to use the space in between to create more homes and give more choice to Ontarians”

— OREA CEO Tim Hudak

Ending single family exclusionary zoning would be an important step forward to improve the supply of housing in the Greater Toronto Area. It will allow us to gradually make existing neighbourhoods far more dense making better use of our existing infrastructure. It would also enable smaller home builders to play a bigger role in the construction of new housing in the Toronto area.

Now all we need is a provincial government that will actually heed OREA’s advice.

Why the one-note 'supply' explanation risks us missing out on other — equally noteworthy — explanations for what is going on in the market.

It has long been argued by many housing analysts and economists that the current price acceleration trends we are seeing in the housing market in the Toronto area are entirely due to a “lack of supply” and that the cause of this lack of supply is municipal and provincial constraints on zoning (see my discussion on this earlier in this report) and “red tape” which slows down the construction of new housing.

While more could be done to remove some supply side constraints (as discussed above), blaming supply tends to be a perennial “one size fits all” solution.

A recent data trend illustrates why this one-note explanation risks us missing out on other — equally noteworthy — explanations for what is going on in the market.

The first problem is a tendency to ignore demand-side explanations.

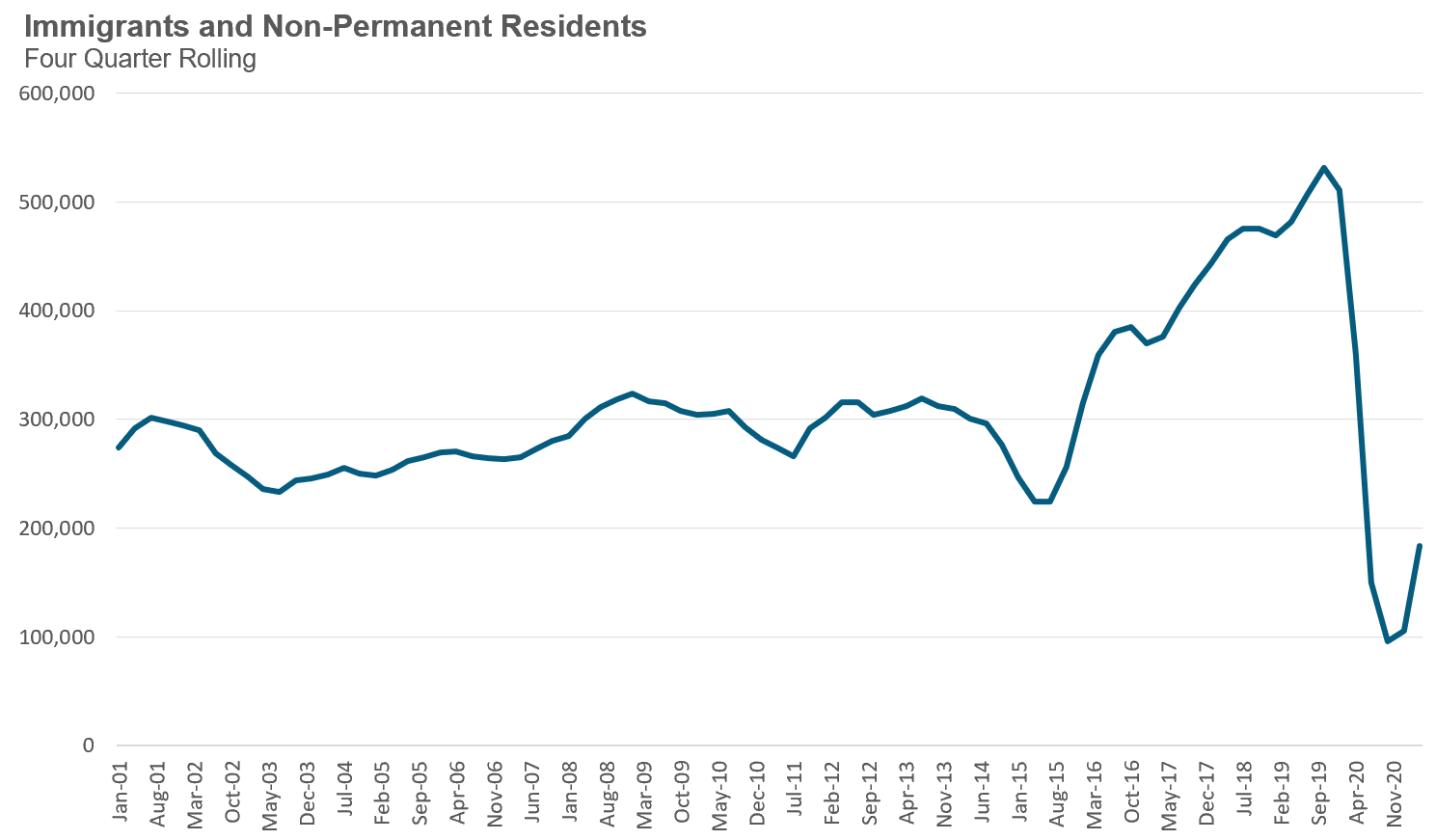

Under the current Liberal government, which first came to power in 2015, Canada has seen a super-charged number of immigrants and non-permanent residents moving to Canada from roughly 300,000 per year to as much as 500,000 just preceding the Covid-19 pandemic (which resulted in a sharp drop in these numbers due to international travel and border restrictions).

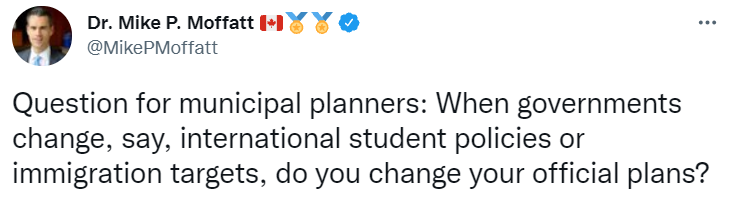

Given this, economist Mike Moffatt recently posed an intriguing question on Twitter:

The short answer to his question is that municipalities don’t change their official plans in response to demand shocks like this — at least not immediately — such plans are typically long-term in nature, reviewed and updated every 5-10 years.

So when our federal government accelerates our population growth and local authorities and market actors like municipalities and builders don’t respond fast enough to accommodate this new demand — the resulting surge in housing prices is pretty much economics 101 as demand is fast outstripping supply under Trudeau’s government.

Another problem is confusing longer-term trends with shorter-term ones and we are seeing some interesting things when it comes to the latter right now.

One of the key drivers behind Toronto’s rapid appreciation in house prices over the past month has been a rapidly declining number of homes available for sale. Last month, there were just 4,607 houses available for sale (“active listings”), well below the 10- year average of 11,368 for the month of September.

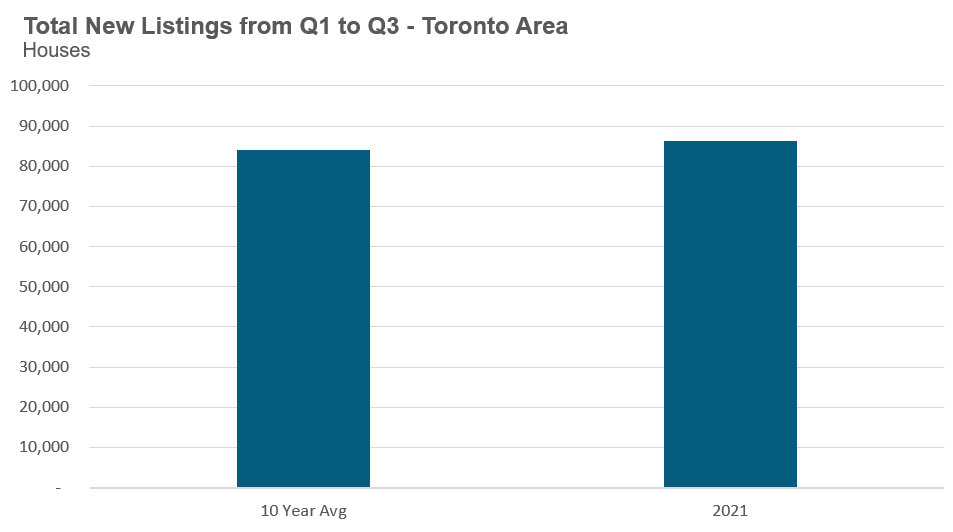

When we look at the volume of new listings that have come on the market during the first three quarters of 2021 in comparison to the 10-year average for those quarters, we see that new listings are 3% ahead of the 10-year average. This suggests that ‘new listing’ levels are not a key driver of the currently low number of ‘active listings’ we are saying, as many have been suggesting on social media and in the media.

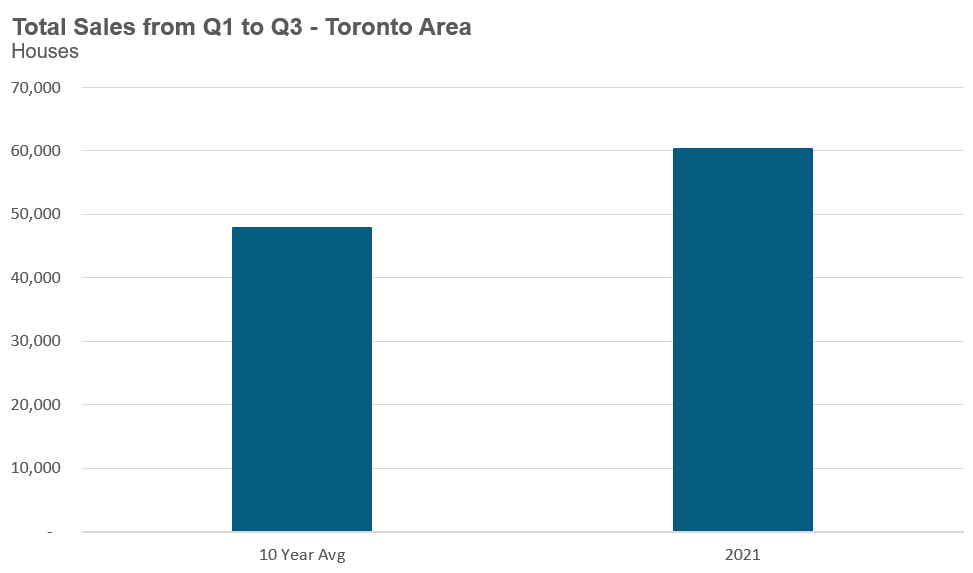

If we look at the number of sales over the same period, the first three quarters this year, against the 10-year average for the same period, we find that sales this year are 26% above the 10-year average. In terms of actual home sales, an extra 12,366 homes sold this year when compared to the 10 year average.

This jump in sales numbers suggests that notably strong demand has been the key driver of this current trend. Given the unprecedented impact of the Covid-19 pandemic, which saw many seeking more spacious living accommodations, coupled with the significant monetary and fiscal stimulus introduced to reduce economic fallout, it’s reasonable to think that these factors may have contributed to a sudden surge in demand for houses in the Greater Toronto Area.

It’s this sudden surge in demand that has resulted in a record low number of ‘active listings’ available. Even though the number of ‘new listings’ was in line with historical trends, the additional 12,366 sales this year, driven by this demand, has resulted in fewer homes being available for sale at any given point in time.

Returning to the supply side, it’s puzzling to see that while sales this year are up 26% over the 10-year trend, new listings are only up 3% over the same periods because a surge in sales would normally lead to an increase in new listings.

A significant number of today’s home buyers (who are contributing to the high number of sales) are also home owners and normally when these owners are upsizing or downsizing to a new home, they sell their current property — which is why we’d expect to see new listings higher than what we’re currently seeing.

One of the reasons new listings haven’t accelerated much is that many homeowners who are upsizing (say from a condo to a house) or downsizing try to hold on to their current home as an investment property rather than sell it.

Recent research published by credit rating agency Equifax found that the number of people adding a fourth mortgage or more (i.e., investors with more than four properties, etc.) surged at twice the rate as the number of first-time borrowers. A recent report from the Canadian Housing Statistics Program also found a sharp rise in the number of buyers looking for investment properties in Canada.

“The people piling into Canada’s red-hot housing market fastest already own a home -- or in some cases three or four.”

- Bloomberg, Sept 29, 2021

We can see this trend as well by looking at how new rental listings have changed over time.

The chart below shows the number of houses listed for rent during the first three quarters of each year in the City of Toronto. Unlike the condo market, where a rise in rental listings is largely the product of new condo building and unit completions, the same is not true for the low-rise house market. Not only is the rate of construction of new low-rise houses much lower, they are not popular with traditional real estate investors as an investment the way that condos are.

Out of all the regions in the Greater Toronto Area, the City of Toronto saw the most dramatic increase in rental listings between the pre-COVID year of 2019 and the current year, an increase of 46%. Part of this is likely due to the Covid-led urban exodus trend over the past year that saw many people abandon urban living in favour of more rural properties. A fair number of these homeowners who relocated appear to have kept their existing homes and simply rented them out rather than selling them.

Of course, a surge in new listings doesn’t necessarily mean that this is the result of people moving out of their houses and renting them out. It’s possible that this is just the product of the high turnover of existing rentals as more renters move out of the city.

To address whether this is the case, we looked at all new rental listings in a given year and looked back in time to see whether the last transaction on the same property was a lease or a sale. If the last transaction was a lease then we considered this property part of the current rental pool (e.g., as an existing landlord appears to be renting out their houses because their current tenants are moving out); however, if the last transaction was a sale, then we classified this as new rental inventory coming on the market (e.g., as these houses were either previously owner-occupied or newly purchased and are newly being rented out).

What we found was that virtually all of the growth in new rental listings in 2021 was the result of properties that had not been rented out before. This gives some weight to the explanation that new rentals, and not just high turn over of existing rentals, are a key part of the story and that part of this is owners who are hanging on to their properties and renting them out when they buy other ones. Anecdotally, at my own brokerage, Realosophy Realty, we are often asked by clients who are looking to buy a new home if we can help them ‘run the numbers’ to see if they can hold on to their existing homes as rental investments.

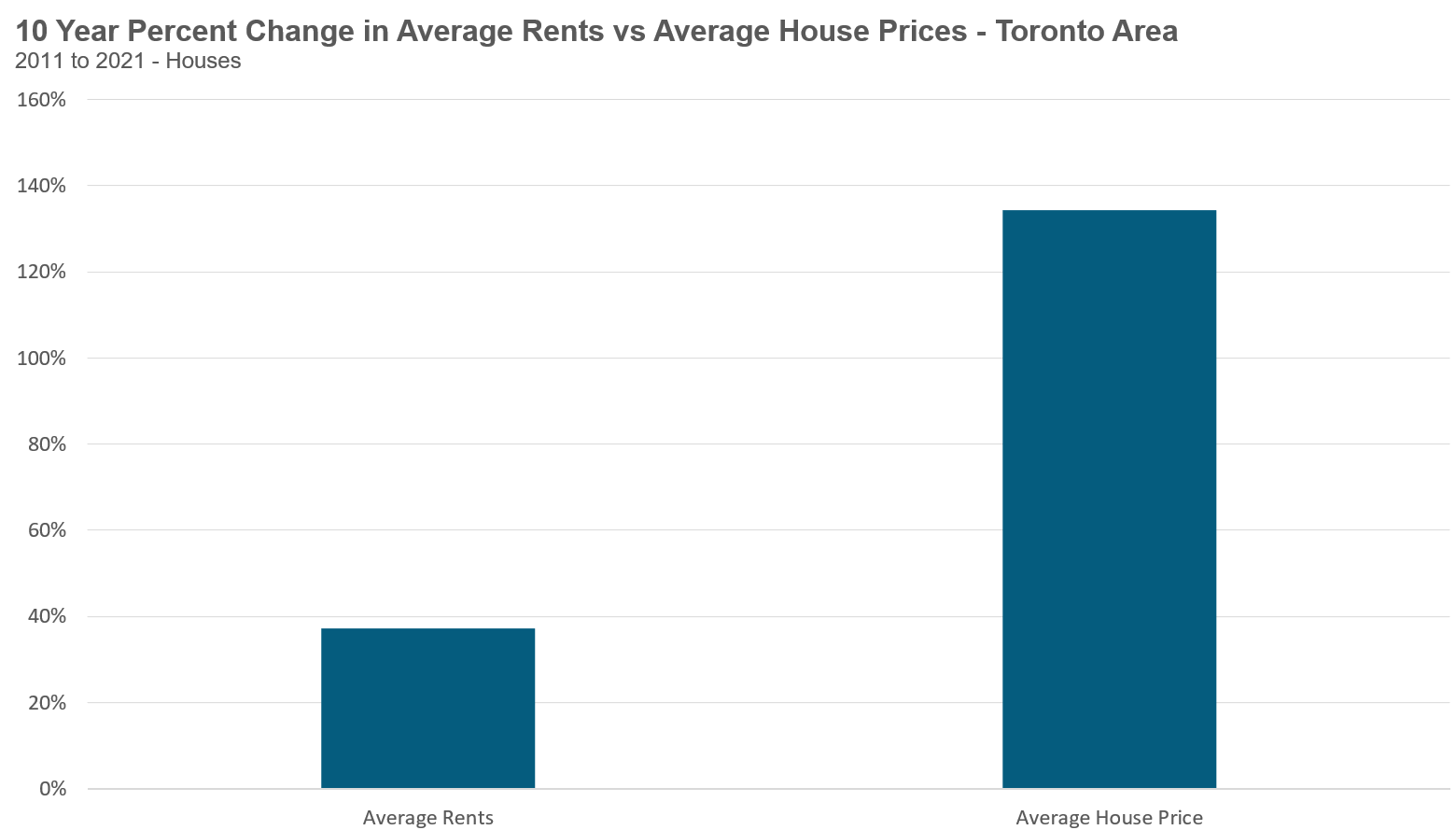

Returning to the issue of housing affordability, I often hear economists arguing that strong demand from investors is a good thing for our housing market since these investors are adding to the rental supply and thus making renting more affordable.

But while house rents are rising at a rate that is slightly above the rate of inflation, house prices have surged 134% in ten years — I think policy makers should be a bit more concerned about how investors might be contributing to the rapid acceleration in house prices.

One policy solution would be to see our government put regular home buyers ahead of wealthy investors by tightening mortgage lending criteria for investors who are buying multiple properties, presumably both increasing supply as fewer homeowners would be able to keep their existing homes after they buy another and reducing demand, which is not a bad thing in a market like Toronto where nearly 1 in 4 homes are bought by investors (according to research from the Bank of Canada).

However, this is not one of the policy proposals put forth by the Liberals in their recent re-election campaign, which, like that of the other parties, focussed largely on the need to build more new housing — which is what happens when you only see ‘long-term supply’ problems regardless of what else the data is actually saying.

September 2021

House sales (detached, semi-detached, townhouse, etc.) in the Toronto area in September 2021 were down 28% over the same month last year.

Sales will likely continue to be negative on a year-over-year basis until at least the first quarter of 2022 since we’ll be comparing against a period that saw a sudden shock in demand for houses following the initial Covid-19 lockdowns. But it’s worth noting that sales in September were above levels for the same month in pre-Covid 2018 and 2019.

New listings in September were down 36% over last year. But unlike sales volumes which were strong compared to pre-Covid levels, new listings in September were well below the listings volumes seen in 2018 and 2019 (for more detail on this, see the ‘Data Dive’ section above in this report).

The number of houses available for sale (“active listings”) was down 53% when compared to the same month last year and 62% below the inventory levels seen in pre-Covid 2019.

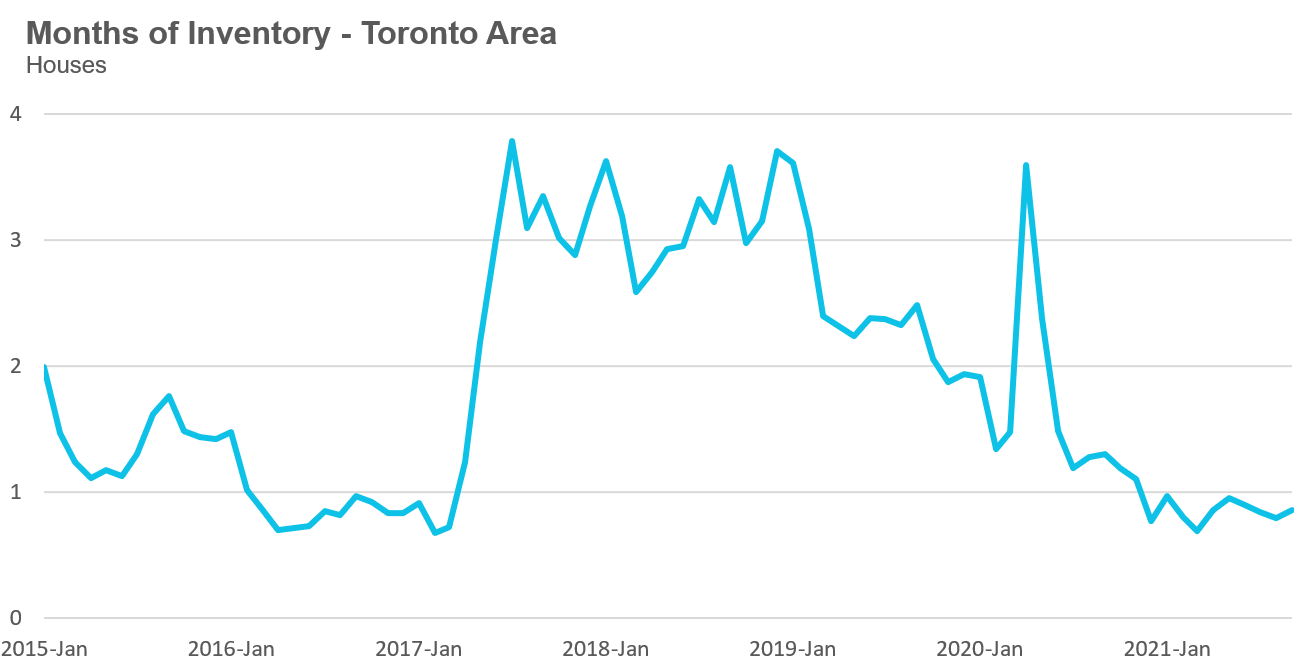

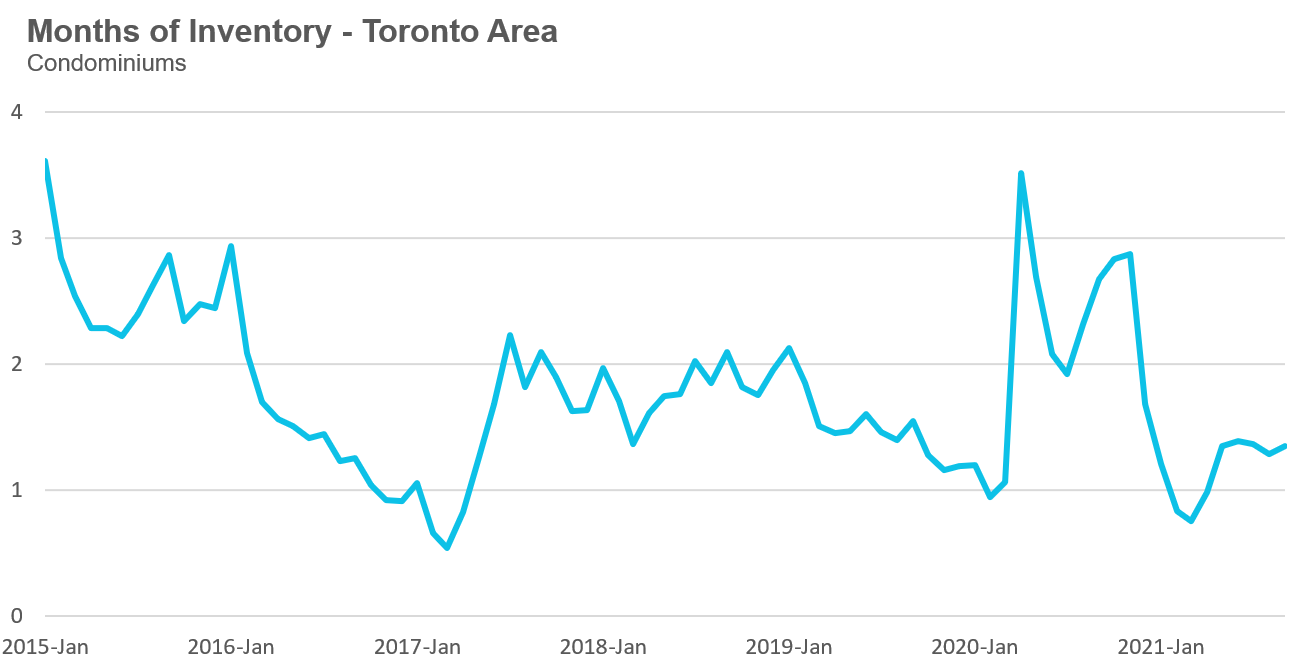

The Months of Inventory ratio (MOI) looks at the number of homes available for sale in a given month divided by the number of homes that sold in that month. It answers the following question: If no more homes came on the market for sale, how long would it take for all the existing homes on the market to sell given the current level of demand?

The higher the MOI, the cooler the market is. A balanced market (a market where prices are neither rising nor falling) is one where MOI is between four to six months. The lower the MOI, the more rapidly we would expect prices to rise.

This September, the market remained very competitive with an MOI of under 1.

While the current level of MOI gives us clues into how competitive the market is on-the-ground today, the direction it is moving in also gives us some clues into where the market may be heading. The MOI has remained relatively stable at or below a very competitive 1 MOI for the past twelve months.

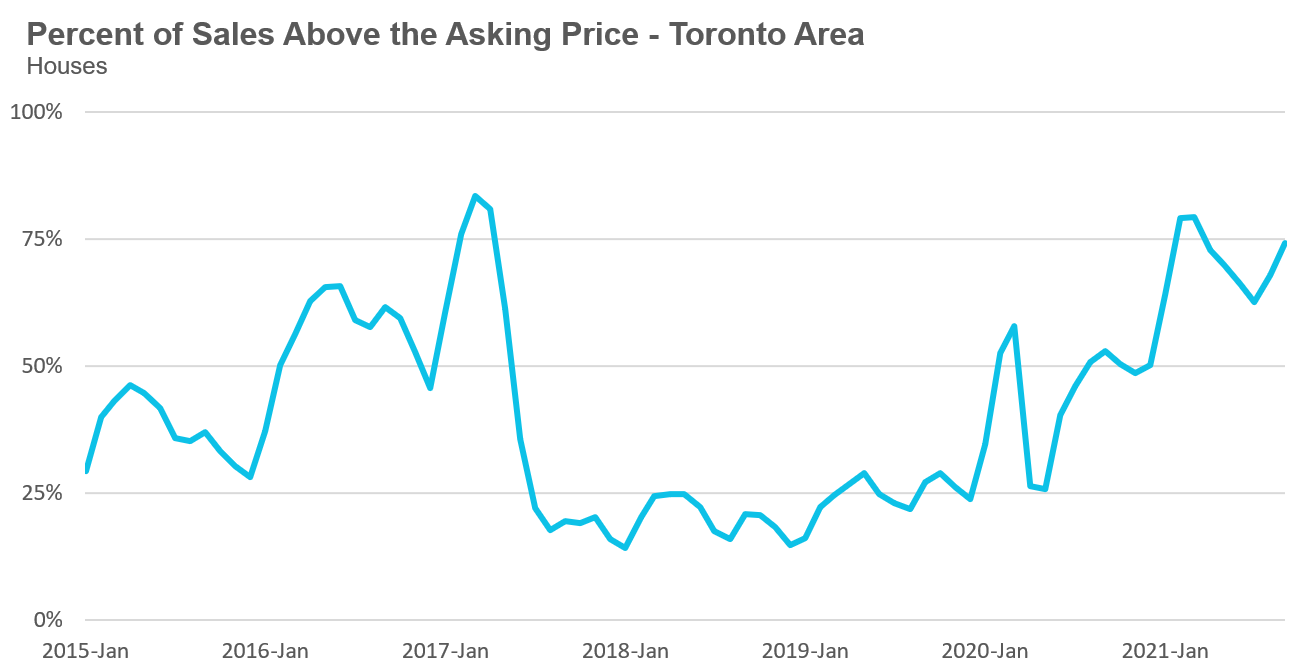

The share of houses selling for more than the owner’s asking price climbed from 68% in August to 74% in September.

Average house prices had plateaued in 2021 remaining relatively constant in the $1.3M range since the start of the year, but that trend ended this September when average prices surged to $1,407,190 up $87,976 or 7% in a single month.

Year-over-year, the average house price in September was up 26% while the median price climbed to $1,225,000, up 29% over last year.

Condo (condominiums, including condo apartments, condo townhouses, etc.) sales in the Toronto area in September were up by 6% over last year and up 22% compared to pre-Covid 2019.

New condo listings were down by 32% in September 2021 over last year, but well above the volumes in 2018 and 2019.

The number of condos available for sale at the end of the month, or active listings, was down 47% over last year, a period that saw a surge in condo listings due to declining prices, falling rents and rising vacancy rates.

The relatively strong demand of new listings (supply) helped keep the MOI at 1.4 for the month of September, up from 0.8 MOI in March.

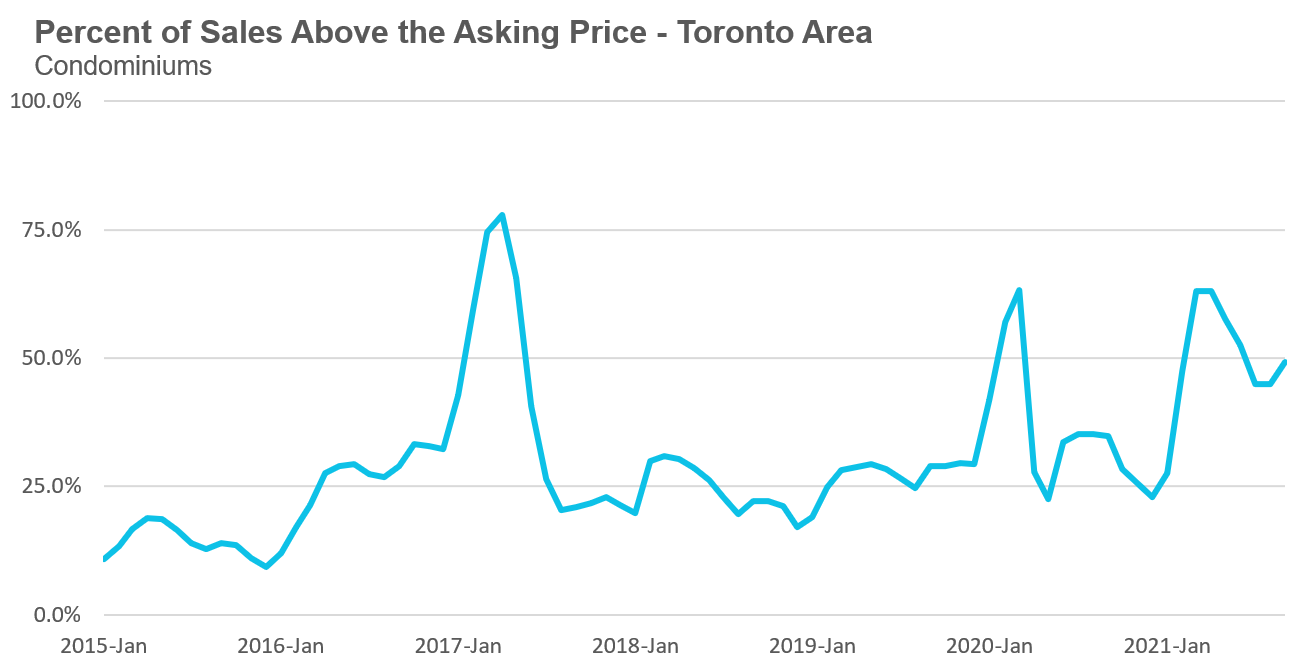

The competition for condos picked up very slightly with the share of condos selling for over the asking price rising from 45% in August to 49% in September.

Average condo prices plateaued at approximately $700K for most of 2021 and in September reached $726,809, up 13% over last year. The median price for a condo in September was $657,500 up 13% over last year.

Houses

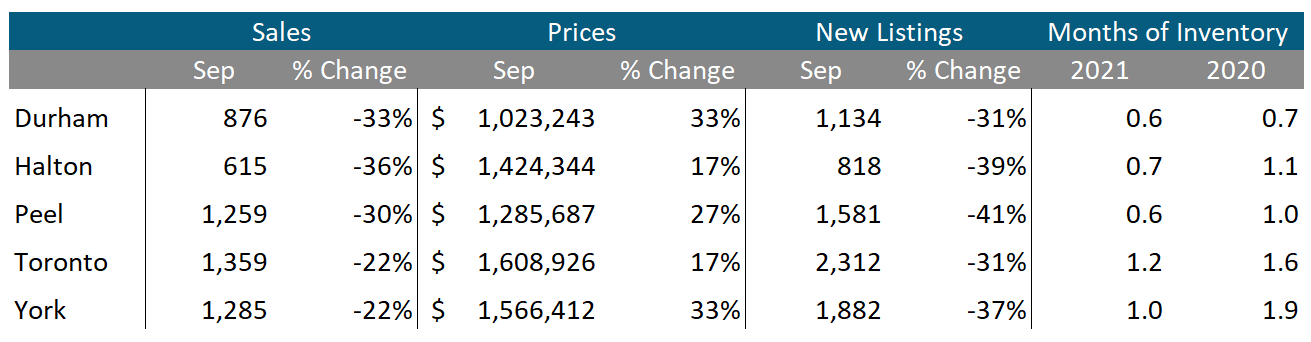

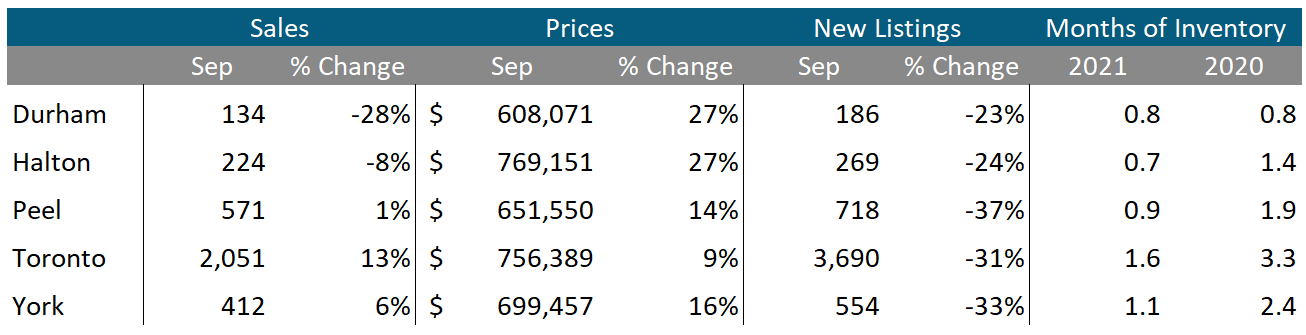

Sales across all five regions in the GTA were down in September while average prices were up on a year-over-year basis. The decline in new listings helped keep the market competitive with MOI at or below 1 across the entire GTA, indicating a strong seller’s market.

Condos

Toronto, York and Peel saw condo sales up on a year-over-year basis while the other regions saw a decline in sales. Average prices were up double digits across the suburban regions and up by 9% in the City of Toronto. Also indicative of strong market conditions, current MOI levels are at or below last year’s levels for all five regions.

See Market Performance by Neighbourhood Map, All Toronto and the GTA

Greater Toronto Area Market Trends