The numbers show that Canada's home prices standout amongst comparable countries.

I was speaking with someone recently who was so used to Toronto’s housing market that he assumed all of the trends and market dynamics we see here are typical and that many cities and countries around the world are experiencing similar trends.

So I thought I’d spend some time in my Data Dive this month to take a look at Canada’s real estate market from an international perspective.

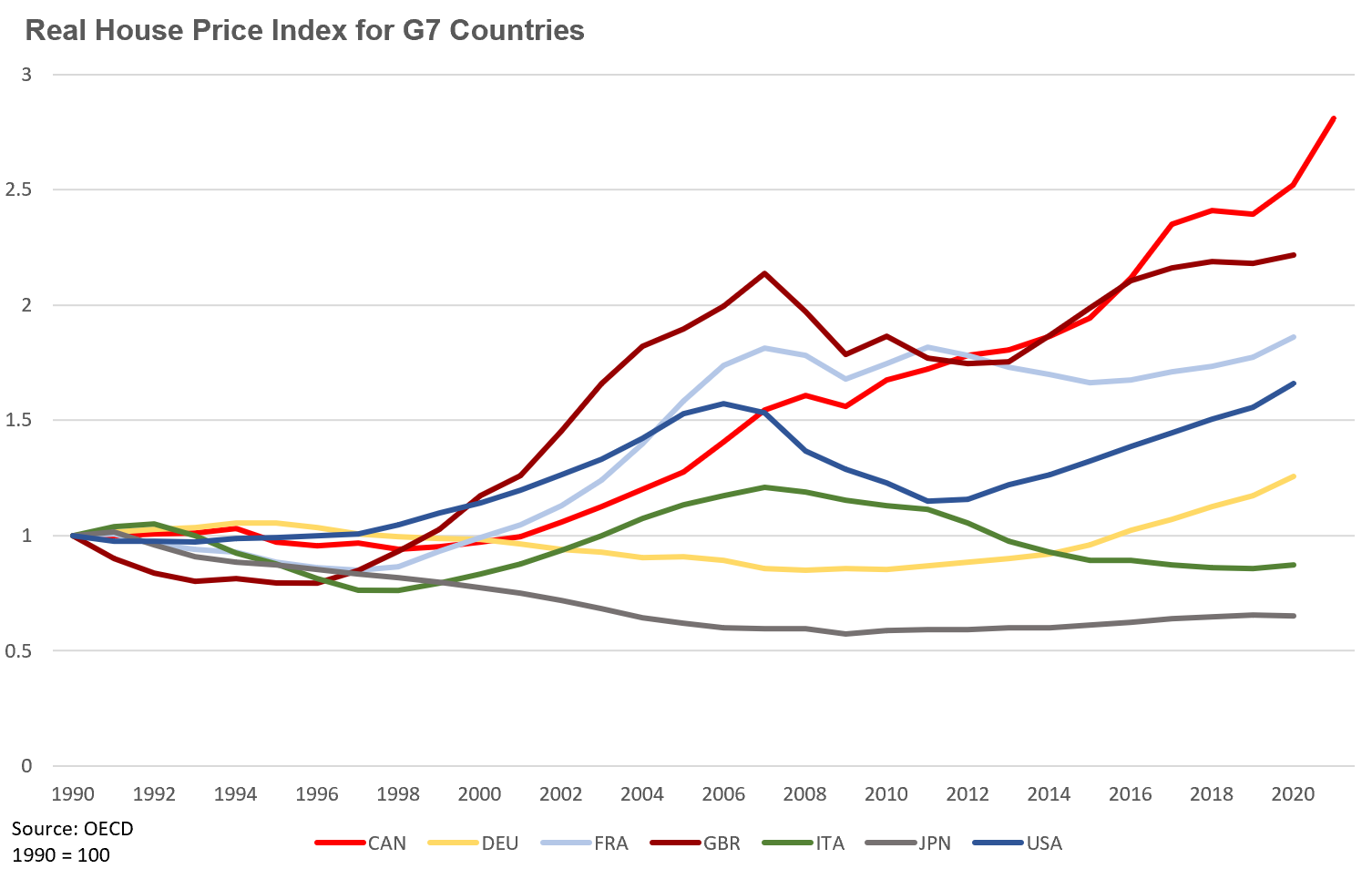

I’m going to start by taking a look at how home prices have changed across G7 countries since 1990.

This chart shows an index of house prices which allows us to compare how prices have changed without worrying about any currency differences. It assumes 1990 is our starting point and then shows how each country's home prices have changed since that time.

We can see that house prices in Canada have outpaced the rest of the G7.

But changes in prices alone don’t tell the entire story. When economists try to assess whether home prices are overvalued relative to fundamentals, one way they’ll do that is by comparing house prices to rents since rents are effectively the annual dividend income we receive on our rental investment.

Another way of thinking about the relationship between home prices and rents is that if home prices rise too rapidly and owning a home becomes much more expensive than renting, households will be more inclined to rent rather than buy. As more households decide against buying and opt to rent, this takes pressure off of rising home prices and gradually puts upward pressure on rents, eventually moving them back towards equilibrium where households are indifferent between buying and renting. At least in theory, this is the relationship between home prices and rents we should see over time in a balanced market.

One of the metrics economists often use to compare home prices and rents is the price-to-rent ratio. Here’s an example of how the price-to-rent ratio is calculated. If a home sells for $500,000 and the annual rental income is $25,000 (or $2,083 per month) then the price-to-rent ratio is 20 since the price of the home is 20 times the annual rental income. Another way of thinking about this is that if I bought this home strictly as an investment, the rental income (before deducting other expenses) would offer me a gross return of 5% per year since the annual rental income of $25,000 is 5% of $500,000.

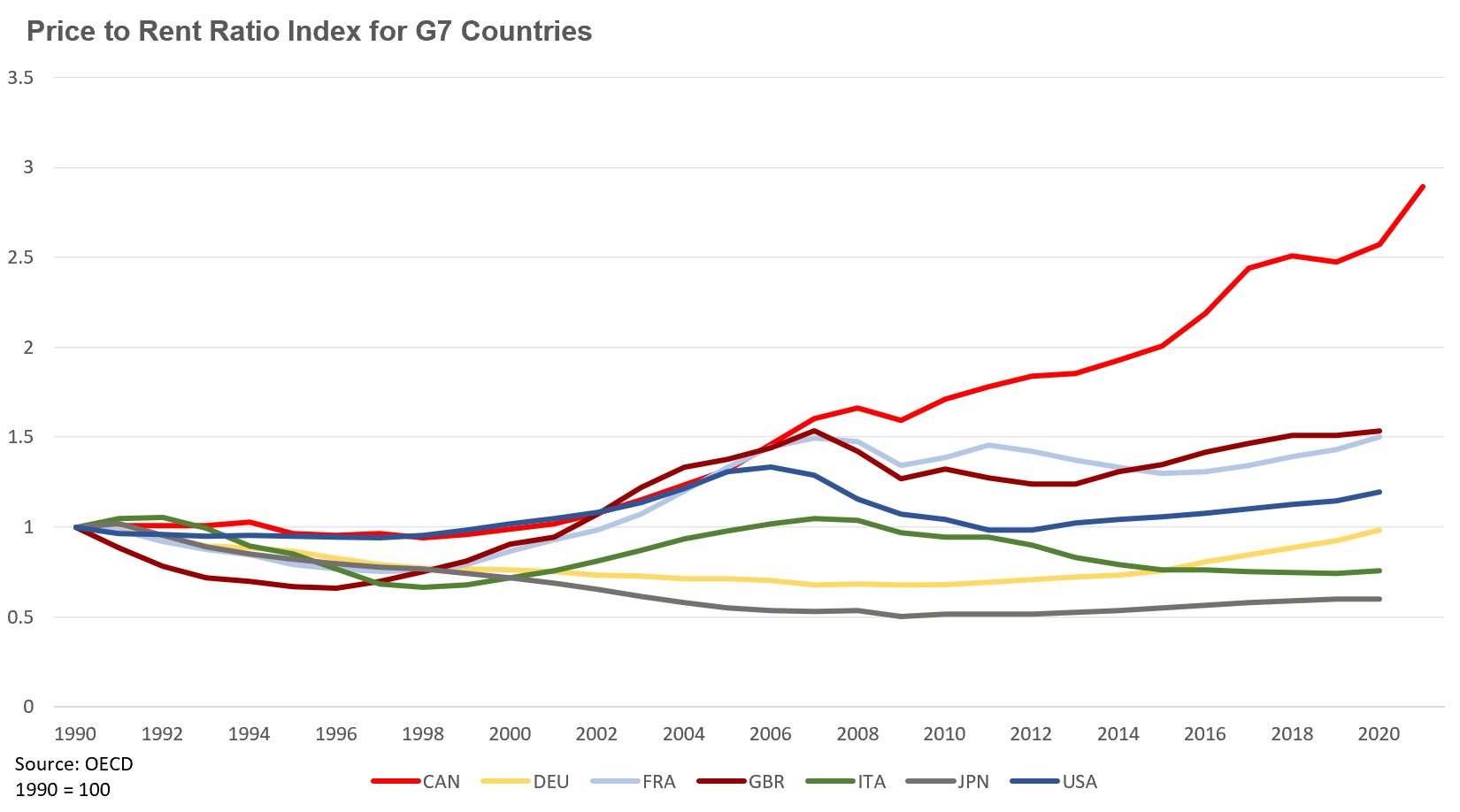

The chart below shows the price-to-rent ratio index for G7 countries. The idea with an index is to measure how the price-to-rent ratio has changed over time — rather than measuring the actual price-to-rent ratio. The chart below sets 1990 as our starting point and then shows how each country's price-to-rent ratio has changed since then.

We can see that by 2006, Canada’s price-to-rent ratio had risen at a similar rate to Great Britain and France.

But since then, Canada’s price-to-rent ratio has accelerated at a much faster rate than all other G7 countries. Canada was the only country with price-to-rent ratio data for 2021.

So what exactly is this chart telling us?

It’s telling us that home prices in Canada have appreciated far more rapidly relative to rents when compared to the other G7 countries — that is, the cost of a home has most rapidly outpaced the rent it earns. In the United States for example, home prices have not appreciated much when compared to rents. In Japan and Italy, home prices have declined relative to rents when compared to their level in 1990.

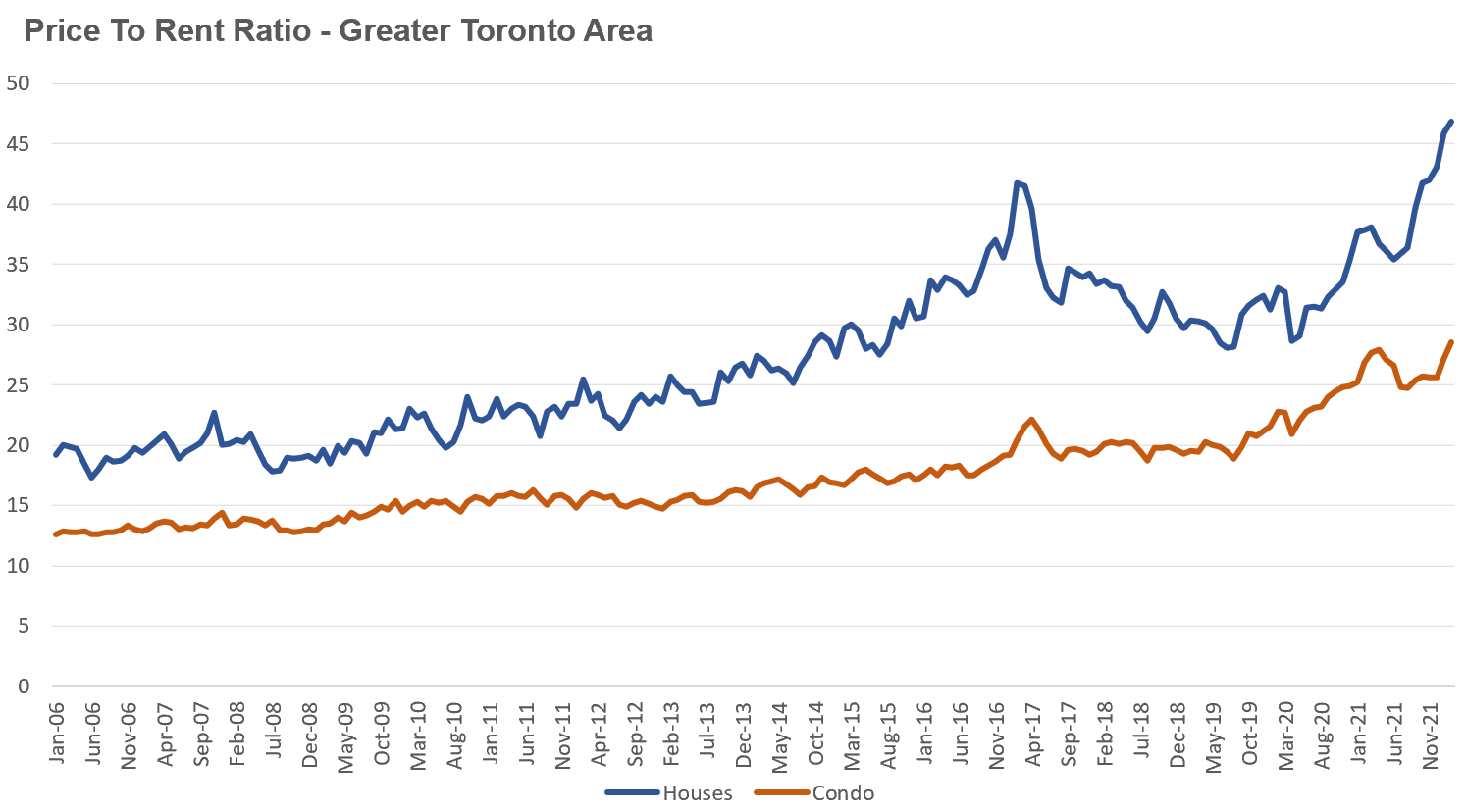

If we turn our attention to the Toronto area housing market, we can compare the change in the actual price-to-rent ratio over time rather than comparing against an index.

Note that the chart above starts in 2006 as compared to 1990 in the previous charts and reflects average sale and rents from the Toronto Real Regional Real Estate Board’s MLS system.

In February 2022, the average low-rise house sold for $1.68M while the average rent for a low-rise house was $2,992 resulting in a price-to-rent ratio of 47.

The average condo last month sold for $836K and the average rent for a condo was $2,443 resulting in a price-to-rent ratio of 29.

This disconnect between home prices and rents we are seeing in Canada, and Toronto more specifically, is not a normal trend — as we can see above when we compare Canada to other G7 countries.

One key factor I’ve discussed before is that Canada’s population is not only growing twice as fast as any other G7 country, but it’s also growing far faster than our ability to build new homes which is pushing home prices higher. Even if the rents don’t justify today’s prices, the expected future appreciation is what is motivating people to buy homes, or in some cases not sell them when they move out of them.

But we are also seeing signs that rents are accelerating, and not just in the Toronto area where average rents have surpassed pre-COVID levels, but in other parts of Canada as well as people arrive from more expensive parts of Canada.

Renters for the most part have not felt the true high cost of housing in Canada since homeowners have largely been absorbing relatively low rents, but that’s starting to change.

As more people get priced out of the housing market, we will see more demand for rentals which will likely put upward pressure on rents in the years ahead.

John Pasalis is President of Realosophy Realty, a Toronto real estate brokerage which uses data analysis to advise residential real estate buyers, sellers and investors.

A specialist in real estate data analysis, John’s research focuses on unlocking micro trends in the Greater Toronto Area real estate market. His research has been utilized by the Bank of Canada, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

Follow John on Twitter @johnpasalis

Email John