This month we look at Toronto's emerging housing bubble in the suburbs, how it's different from 2017 and how it will end this time around.

As Featured in the Move Smartly Report:

Special Client Seminar - Wed Feb 17 12PM ET (Noon)

Join John as he unpacks this month's report and answers your questions. Exclusive for Realosophy past & present clients.

Toronto’s Suburban Housing Bubble

Two months ago, I wrote about bubble-like conditions in Toronto’s suburban housing market.

At the time, house prices were appreciating by 15 to 20% per year and there were plenty of signs that things were going to get even hotter. Many houses for sale were receiving upwards of 20 to 30 offers from buyers and the prices that buyers were paying were starting to look irrationally high.

When looking at the actual sales and inventory data, all signs were pointing to a market that was going to get hotter in the next few months with no signs of cooling.

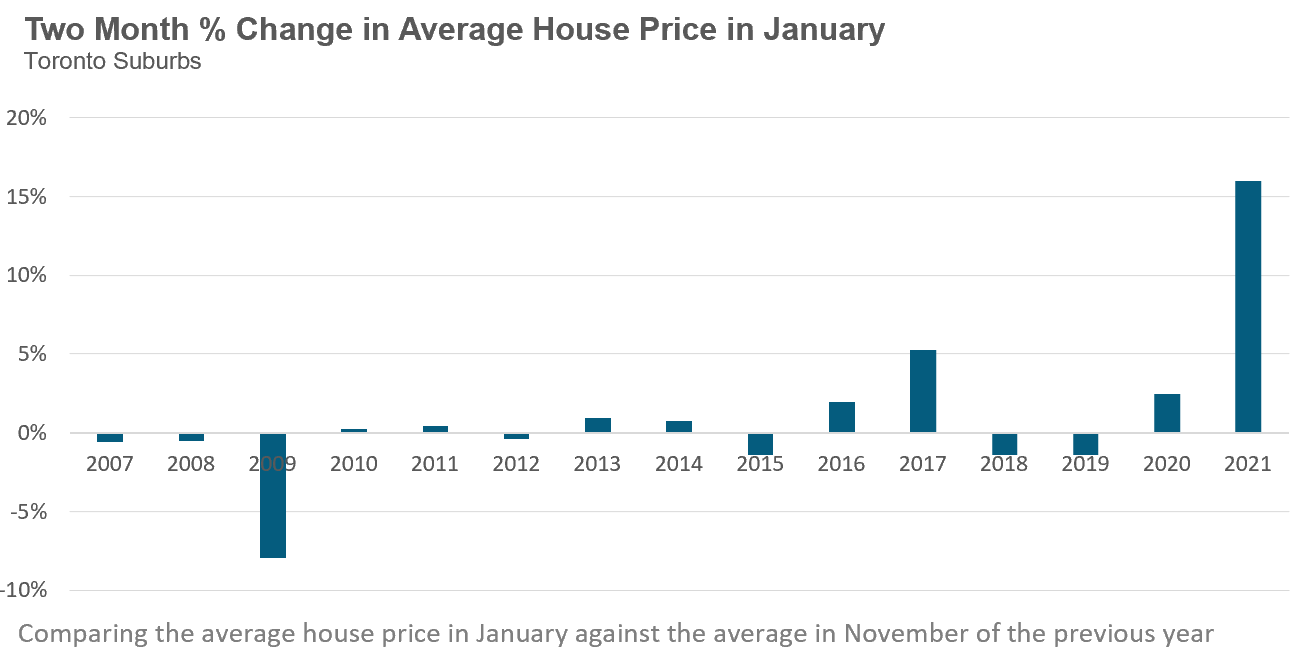

Unfortunately, this is precisely what happened. In the two months since that report, average sale prices for suburban homes have surged 16% from $1,052,940 in November 2020 to $1,221,092 in January 2021. Median prices are up 14% over the same period.

While we don’t typically compare house price changes on a month-over-month basis because seasonal differences can impact the average, it’s worth noting that average prices rarely change very much during the two months from November to January.

Below is a chart showing the 2 month change in average house price for suburban houses between November and January since 2007. You’ll note two outliers in the trend (aside from last month). The decline in 2009 was during the financial crisis and the 5% increase in 2017 was leading up to the peak of Toronto’s last real estate bubble.

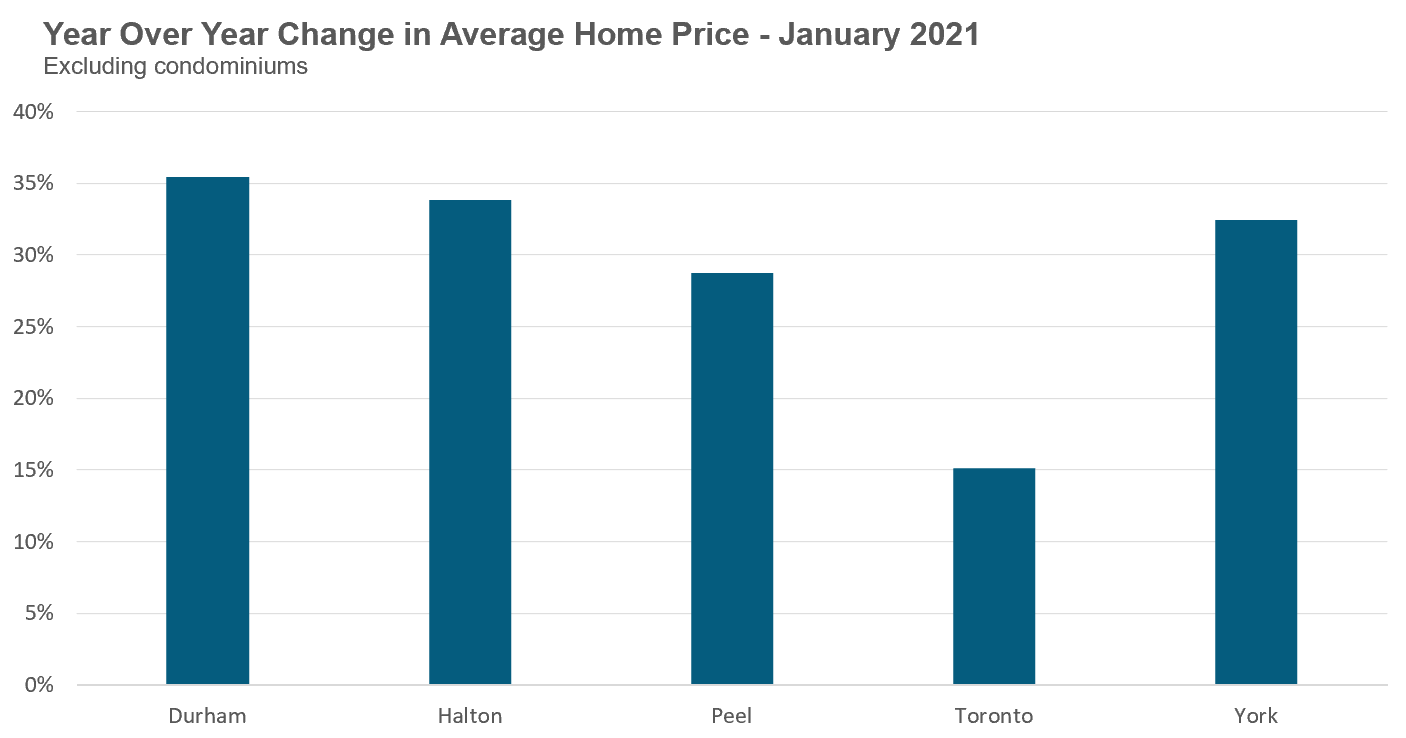

When comparing average sale prices in January 2021 on a year-over-year basis we see that average prices in Toronto’s suburbs were up by over 30% in Durham, Halton and York regions and by 29% in Peel Region. Prices in the City of Toronto were up a more modest 15%.

Suburban house prices have been accelerating since the first quarter of 2020 and after hitting a short pause during the spring lockdowns continued their trend up.

What Makes it a Bubble?

While some economists and authors have been calling Toronto’s housing market a bubble for the past 10 to 15 years, I’m far more reluctant to use the ‘B’ word. I reserved it for periods when on the ground observations of market exuberance line up with the quantitative data.

The last time I felt there was a bubble in Toronto’s market, I wrote about it as early as the summer of 2016.

House prices continued to accelerate after that ending 30% up year-over-year in the first quarter of 2017. And then, just as quickly, prices suddenly declined in the 2nd and 3rd quarters of 2017, catching buyers and sellers off-guard and scrambling to manage amidst such a quick correction.

The academic literature on housing bubbles suggests that they arise under these two main conditions:

- House prices must be high relative to their fundamental value - which is typically measured by comparing house prices to either incomes or rents

- The deviation from fundamentals is largely driven by behavioural factors, such as “irrational exuberance.”

What does this mean in plain English?

The first condition is the one that trips up most economists and analysts. They often assume that house prices appearing overvalued relative to fundamentals such as incomes or rents alone signals the presence of a bubble - but being overvalued isn’t sufficient.

For example, if house prices are above their fundamental value in a given city, but are only appreciating by 3% per year then we would think of that city as being overvalued but not necessarily in a bubble, which leads us to the second requirement of a housing bubble.

Irrational exuberance generally refers to periods when people’s motivation for buying a home and the price they pay is driven by a belief that prices will keep going up forever.

An example of this is when investors pay high prices for homes that can’t be justified by the rental income they could expect to generate and accept a negative monthly cash flow because they believe that this will be offset by the house being worth 10 to 20% more in a year’s time.

Another example is when home buyers are led to overpay for houses out of a fear that if they don’t buy a home today, houses will appreciate $100K more in six months, out of their financial reach.

Both of these are examples of the motivations that drove investors and buyers during Toronto’s 2016/2017 housing bubble, which led to prices rising by over 30% per year.

Such behavioural trends are of course very difficult to quantify.

Measures that aim to quantify demand from investors at any given point in time often lag the market. For example, if an investor buys a home today they may need to wait three months before they take ownership and an analyst may need to wait an additional 3 to 6 months to see if the investor tries to rent the house or sell it on quickly. This means that any concrete measure of the number of properties purchased by investors in January 2021 would take approximately 6 to 12 months to show, by which time a bubble could already be underway.

Measuring consumer sentiment is even harder with most academic research relying on surveys of home buyer beliefs after purchase. But the 16% appreciation in home prices from November to January gives us clues into how home buyers are behaving on the ground.

In a competitive market, there are always going to be some home buyers who pay far above the market value of a home. But in a normal market, home buyers perceive these relatively few transactions with inflated sale prices as outliers by misinformed or irrational buyers.

But what happens when the misinformed or irrational buyer is no longer the outlier - but the norm. What happens when the majority of buyers are paying $50-$100K more for a house today than what a similar house sold for a month ago? This is precisely the trend we have been seeing on the ground since November and is now being reflected in the data.

When this keeps happening, a house that would have sold for $1.055M at the beginning of December is selling for $1.22M at the end of January. This rapid acceleration in house prices is a textbook example of irrational exuberance in the market.

Lastly, it’s worth discussing one final characteristic of a housing bubble which I touched on earlier.

The rate that house prices appreciate in a given city is typically relatively stationary over time. For example, assuming an average rate of appreciation for suburban houses in the Toronto area of 6%, we may see price growth bounce around in some range between 2 to 10% during most months depending on short term dynamics, but we are not going to see house prices down 10% one month and up 30% the next as price changes are not that volatile.

That’s why I suggested earlier that a housing market could be overvalued, but not in a bubble if prices are rising within the market’s longer term trend.

But if the rate of growth in house prices begins to accelerate, moving further and further away from its longer term trend then it is more likely that the surge in house prices is indicative of a housing bubble.

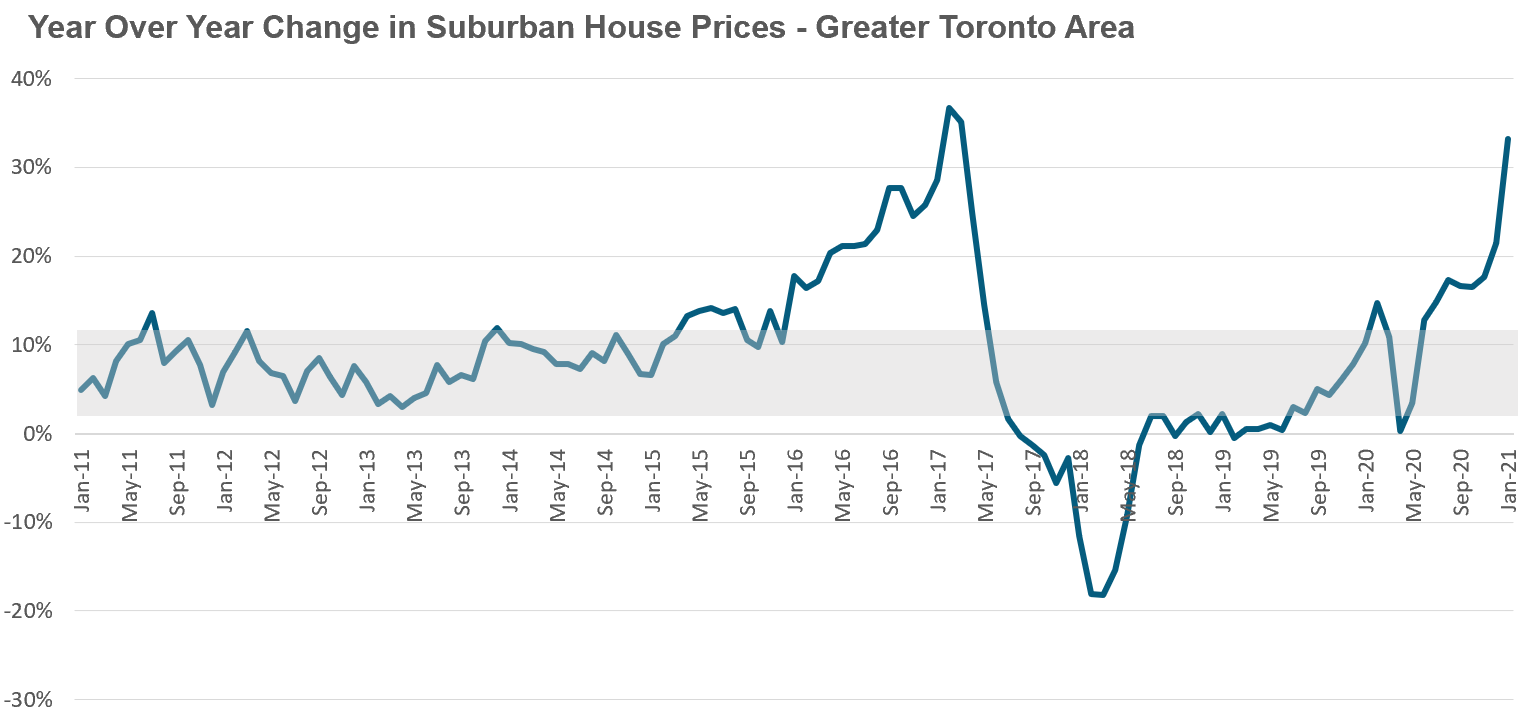

Let’s see what this might look like with some actual data. The chart below shows the year-over-year change in house prices (excluding condos) in Toronto’s suburban markets (Durham, Halton, Peel and York regions).

Let’s assume for a moment that the grey band represents the long term appreciation range for suburban house prices. Minor deviations from this range, like in late 2018 and early 2019 when price growth was below the range is not particularly alarming and can be caused by policy changes that tighten mortgage lending, for example.

But when the rate of appreciation in house prices moves above the band and continues to move further and further away from the historical trend - like it did in 2016/17 and like it’s doing today - then this explosive growth in the rate of change in house prices is a trend that is typically indicative of a housing bubble.

How is Today’s Bubble Different from the 2017 Bubble?

In 2017, I published a report that argued that a key factor behind the acceleration in house prices in 2016 was a surge in demand from investors who were buying single family houses in the suburbs in order to rent them out.

Today’s bubble is quite different. Firstly, the demand for suburban houses to date appears to be, based on anecdotal observations, largely driven by end users rather than investors.

While COVID-19 cooled the market in the second quarter of 2020, it also supercharged the demand for houses in the suburbs once buyers reentered the market in June and July.

This demand surged because of a shift in preferences from home buyers and homeowners as a result of the need to work and school from home due to the pandemic; urban homes and small condominiums became less desirable and buyers suddenly wanted larger houses that had enough room for home offices and plenty of space inside and out for families to use.

This pandemic-induced demand introduced a new wave of buyers who were not previously looking to buy a home and their decision to leave the city amplified demand for houses in Toronto’s outer suburbs.

In fact, out of the top ten fastest appreciating neighborhoods in the GTA in 2020, nine were in the suburbs and four of them were in rural areas where lot sizes were frequently measured in acres not feet.

Another key factor driving demand was a decline in mortgage rates. In early 2020, buyers were paying just under 3% interest on their mortgage while today’s home buyers can get a mortgage in the 1.5% range. This drastic decline in borrowing costs has made the carrying costs of owning a home much lower - provided you have a down payment big enough to get into the market in the first place.

Another big difference with today’s suburban housing bubble is that the acceleration in house prices has been far more rapid than it was in 2016.

One way to see this is to consider how many months it took for house prices to appreciate by single digits to over 30%. In 2017, it took 25 months — this year it took just eight months.

While the single digit price growth in April and May 2020 was largely due to the COVID lockdowns, it’s still noteworthy that the market went from a virtual standstill with practically no price growth to over 30% growth in just eight months.

It is this rapid acceleration that has seen the return of a particular species of investors that haven’t been seen in some time - house flippers!

When I say house flippers, I don’t mean the type one might see on HGTV where enterprising real estate entrepreneurs buy a fixer upper, renovate it and then try to sell it for a profit.

I mean the type of flippers that buy homes, do absolutely nothing to them and then sell them 6 to 9 months later for a big profit.

This type of speculation is only possible because of the rapid acceleration in prices we have seen over the past few months. It’s very common to see these investors selling their properties for 20 to 25% more than what they purchased them for 6-9 months earlier - without doing any work to the property.

Because real estate is a highly leveraged investment (buyers only need to invest 5-20% of the value of the house as a down payment and borrow the rest), after deducting the transaction costs on these flips many of these investors are more than doubling their initial investment. .

I suspect that many of these flippers came about their windfall accidentally - they likely did not buy with the intention of flipping their properties in a very short period of time without doing any work to the property. In some cases, these flippers bought with the intention of renting the house, but when they were unable to find an acceptable tenant opted to cash out and sell their property. In other cases, they may have intended to renovate and flip, but decided it would be easier and more lucrative to flip the house without investing any money in it.

It’s also worth noting that properties being flipped (with or without renovations done to them) make up a relatively small share of the market today. In January 2021, roughly 6% of all the houses that were listed for sale in the suburbs were bought during the previous 12 months, up from 4% a year ago.

But I suspect this trend may accelerate as we head into the spring market for a couple of reasons.

Firstly, these first flippers made a significant amount of money in a very short period of time and that’s the spark that is needed to fuel more investors to want to do the same thing.

It’s helpful to consider economist Robert Shiller’s definition of a housing bubble to see how word of mouth and investor success stories amplify the exuberance in the market.

A situation in which news of price increases spurs investor enthusiasm which spreads by psychological contagion from person to person, in the process amplifying stories that might justify the price increase and bringing in a larger and larger class of investors, who, despite doubts about the real value of the investment, are drawn to it partly through envy of others’ successes and partly through a gambler’s excitement. -Robert Shiller

The second reason is that we are in the middle of a booming housing bubble that investors believe the government will do everything in their power to keep going.

In a normal market, policy makers would typically be concerned to see house prices rising by over 30% per year and at a minimum would caution markets of the risks of this type of acceleration and that measures may be introduced in the future to cool the market.

In short, the message investors would normally get from governments is that they don’t like the trend they are seeing and they may step in to end it.

Things are quite different today. To start with, there appears to be absolutely no concern about the rapid acceleration we are seeing in house prices from our government or our central bank.

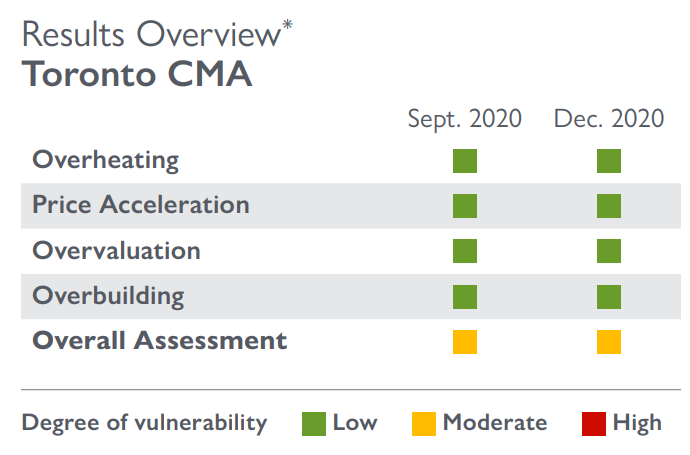

In December 2020, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) concluded that there was a low risk that house prices in Toronto were overvalued and a low risk of overheating and price acceleration. They came to this conclusion a month before suburban house prices in Toronto were up by more than 30% year-over-year.

Now, in CMHC’s defence, Toronto’s housing market is made up of many different submarkets and not all are overheating. But to suggest that the risks in Toronto as a whole are low, when house prices in the suburbs were up more than 30% year-over-year a month after their report seems quite odd. What can the average home buyer take away from CMHC’s conclusions? That prices rising by 30% year-over-year in the suburbs is normal?

Now, in CMHC’s defence, Toronto’s housing market is made up of many different submarkets and not all are overheating. But to suggest that the risks in Toronto as a whole are low, when house prices in the suburbs were up more than 30% year-over-year a month after their report seems quite odd. What can the average home buyer take away from CMHC’s conclusions? That prices rising by 30% year-over-year in the suburbs is normal?

The message from the Bank of Canada last month was very similar — no worries about a housing bubble.

“So far we are not seeing the kind of excessiveness in the housing market that would really get us worried,” Bank of Canada governor Tiff Macklem said, before going on to say that they “start to get worried when people buy houses for the sole reason of thinking the price will go up”. But I don’t think real estate investors see this as a genuine concern.

The overriding message from Ottawa has been that interest rates will be low for a very long time and if the economy sputters (including the housing market), they have plenty of tools at their disposal to kickstart the economy. It’s this forward guidance that is leaving investors overly confident that house prices will only be going up in the years ahead.

I don’t blame investors for wanting to jump into this market. The consensus view from the investors I hear from is that if you’re going to invest in a housing bubble,- you want to ride the bubble that governments are supporting on the way up and the one they’ll throw every policy tool available at to avoid a decline in house prices should things cool.

How is the Bubble Going to End?

Nobody has any idea how this is going to end as these things are unpredictable. That being said, I’ll share with you some thoughts on what the year ahead might look like.

Let’s tackle the most important question on the minds of most home buyers — are prices going to crash this year?

I think it’s unlikely that we’ll see prices fall in 2021.

To paraphrase economist Paul Krugman, housing bubbles don’t end with a pop but with a hiss.

What he means by that is that housing bubbles typically deflate slowly and the first signs of the bust is not a decline in prices but falling sales and rising inventory.

The suburban housing market is so far into seller's market territory that even if the number of homes for sale doubled overnight, this would not be enough to cause prices to fall - it would just slow down the rate of house price appreciation. For prices to fall, something dramatic would have to happen that would significantly cool the demand for houses and also lead to an increase in supply.

The astute reader may note that something like this did in fact happen in 2017.

While house prices in Toronto’s suburbs did fall quite rapidly in 2017, this was a relatively unique event where the introduction of a provincial foreign buyer tax led to considerable fear that home prices would fall. This caused buyers to suddenly pull out of the market just as sellers were rushing in to sell at the peak and this imbalance between demand and supply resulted in a sudden decline in prices.

This type of incident is far less likely to happen again.

This happened during a time when governments did not want to see house prices rising 30% per year and were introducing a policy designed to cool the market.

Things are different today.

Our federal government and the Bank of Canada are not concerned about the rapid acceleration in house prices and have made it quite clear that they want to keep the housing boom going and have plenty of tools at their disposal to ensure this happens.

If demand for houses begins to cool, they could follow through on their plans to relax the stress test, they could increase maximum amortization periods and they could push interest rates lower. Any one of these policy changes could bring buyers back to the market.

The one caveat to this of course is what if a rapidly cooling housing market is limited to Toronto’s suburbs while the rest of Canada’s housing market continues to boom? In a case like this, governments would be less likely to make any drastic policy changes to stimulate the housing market since doing so would overstimulate the rest of Canada’s housing markets.

So if a sudden crash in prices is unlikely to happen in the short term, what might happen?

The ideal outcome would be a gradual cooling down over the next 3 to 6 months.

We will hopefully see some of the heat come off of the housing market over the next few months as the number of new listings increases. The first two months of the year are traditionally the most competitive in the housing market because it’s when most buyers start their home search which means the number of buyers in the market is quite high, but the number of homes for sale is low.

That being said, I’m not convinced that the increase in new listings alone is enough to really cool the market. We’ll likely also need to see a decline in the demand for houses to see the market return to a more balanced level. A decline in demand can happen for any number of reasons including buyer fatigue, declining economic conditions and/or fears about the future outlook of the economy and/or housing market.

A decline in demand would take some of the heat out of the market and would ideally lead to an increase in inventory and a decline in the rate that house prices are appreciating.

As long as house prices are still rising one would hope that policy makers would not feel the need to stimulate the market by relaxing mortgage rules.

The Worst Case Scenario

Alternatively, if we see an increase in demand from real estate speculators looking to flip houses in a short period of time then the rapid acceleration we are seeing in house prices today could continue for some time.

As more and more investors jump into the market this will increase the demand for houses pushing prices higher making their investment returns a self-fulfilling prophecy -- at least in the short term.

Toronto’s housing market has all the key ingredients to make this a possible outcome:

1. Homeowners with plenty of cheap money to invest,

2. Overconfident investors who believe that home prices can only go up in the GTA.

3. A government and central bank that has made it clear they’ll do everything they can to keep the economy and housing market booming.

When I was in Dubai in 2017 to assess their housing market and policies, I heard firsthand how this type of speculative investing resulted in a more than 50% decline in prices in 2009-2010. As a result, the government began monitoring the share of properties being flipped in a short period of time and if the number surpassed a certain threshold it would trigger an automatic fee payable by the seller to discourage sellers from flipping.

This is definitely not the path we want to find ourselves on.

Keeping an Eye on the Market

Read my full analysis on this and other key trends in the February 2021 Move Smartly Report

Follow John's latest updates on Twitter, YouTube, Facebook or Instagram

John Pasalis is President of Realosophy Realty, a Toronto real estate brokerage which uses data analysis to advise residential real estate buyers, sellers and investors.

A specialist in real estate data analysis, John’s research focuses on unlocking micro trends in the Greater Toronto Area real estate market. His research has been utilized by the Bank of Canada, the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF).